Syrians arrested amid Gaza protests face deportation from Jordan

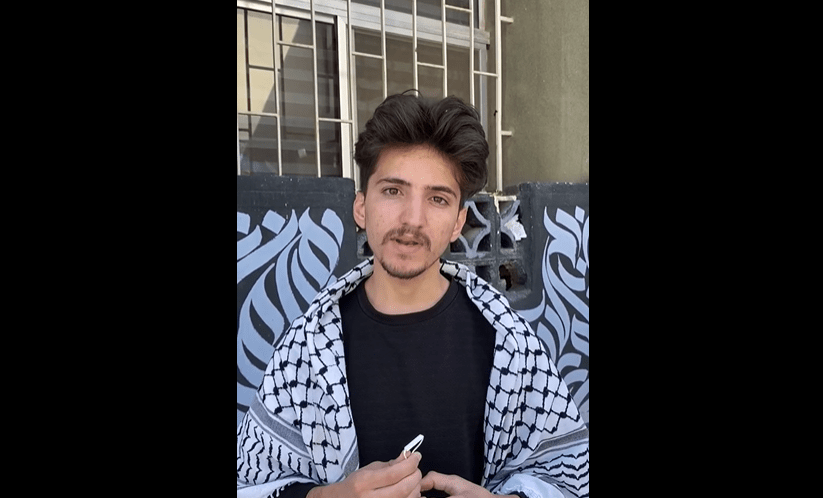

Atia Abu Salem, a Syrian refugee in Jordan arrested on his way to a pro-Gaza demonstration this month, is facing deportation. The families of “many Syrians” among the more than 1,500 people detained amid recent protests are keeping quiet, afraid of “escalation.”

23 April 2024

AMMAN/PARIS — Atia Abu Salem, a refugee in Jordan, is facing deportation back to Syria. He and a Jordanian friend were on their way to film a demonstration in Amman in support of Palestinians in Gaza on April 9 when they were both arrested.

Six days later, Jordan’s Ministry of Interior issued an order to deport Abu Salem, a 24-year-old student at the Faculty of Mass Communication at Yarmouk University in Jordan’s northern Irbid governorate. The April 15 order, which Syria Direct obtained a copy of, stipulates “the above-mentioned person be removed from the territory of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan and barred from returning in the future.”

The document does not indicate where Abu Salem would be deported to, but Jordan has recently deported Syrians to the Rukban camp, a beleaguered desert settlement in no-man’s-land near the United States’ al-Tanf military base just across the country’s northern border with Syria.

“Abu Salem was not brought before the public prosecutor, and no charge was filed against him,” his lawyer, Ahmad Sawai, told Syria Direct. While Abu Salem was ordered deported, his friend, a Jordanian national, was released on bail “after he was subjected to several violations, such as searching his phone and arresting him without charge,” Sawai added.

Abu Salem is from Syria’s southern Daraa province, and comes from a family known for its opposition to the Syrian regime. They fled to Jordan in 2013, after Abu Salem’s father was killed by regime forces. If deported, his life would be in danger.

As human rights activists reacted to Abu Salem’s case this month, the story of another young Syrian came to light. Wael al-Ashi, who also faces deportation, was arrested when Jordanian authorities raided his apartment looking for his roommates, who had participated in demonstrations in support of Gaza. Al-Ashi had not, but was arrested alongside them.

“Many Syrians are being held” in Jordan against the backdrop of ongoing Gaza demonstrations, Sawai said. News of their arrests has not spread—unlike those of Abu Salem and al-Ashi—because relatives “do not want to speak out,” he added. “They fear escalation, and stress the need to not intervene in their children’s cases.”

Jordanian authorities have detained at least 1,500 people, mostly Jordanian nationals, since October 2023, rights organization Amnesty International reported this month. Reina Wehbi, Amnesty International’s campaigner on Jordan, called on Amman to “immediately release all those who have been arbitrarily detained” and ensure the freedom of protesters and activists to “peacefully criticize the government’s policies towards Israel without being attacked by security forces or violently arrested.”

Since the start of Israel’s war on Gaza, launched following a deadly Hamas attack on October 7, Jordan has seen ongoing solidarity demonstrations in several governorates and protest sites. Particularly sensitive are protests that set out from the square of the al-Kalouti Mosque, a 15-minute walk from the Israeli embassy in Amman, which are met with a heavy security presence.

Jordanian security forces have forcibly dispersed protesters outside the Israeli embassy in multiple demonstrations, and have imposed new restrictions on protests in support of Palestine. These include “prohibitions on holding the Palestinian flag and banners with certain slogans” as well as a ban on the participation of children under the age of 18 and protests after midnight, according to Amnesty International.

“After those participating in protests are arrested, they are transferred to the administrative governor who uses his customary powers” to hold them in administrative detention, Hiba Zayadin, a senior researcher in the Middle East and North Africa Division at Human Rights Watch, told Syria Direct. “They are only released by paying bail, even though none have been convicted of the crime of unlawful assembly, meaning that their gathering is peaceful and legitimate,” she added.

“We see Jordanian authorities trampling on the right to freedom of expression and assembly in an attempt to repress activity related to Gaza”

“Administrative detention is an illegal measure, and we see Jordanian authorities trampling on the right to freedom of expression and assembly in an attempt to repress activity related to Gaza,” Zayadin said. Abu Salem and al-Ashi are “at risk in Syria,” she stressed, while “Syria is not safe for any kind of refugee return.”

Abu Salem’s deportation is also illegal under the principle of non-refoulement in customary international law, which prohibits governments from returning people to countries where they have a justified fear of persecution or other serious human rights violations.

‘Our situation is unstable’

Since October 2023, Alia (a pseudonym) has had a heavy heart. Each piece of news coming out of Gaza—where more than 34,000 people have been killed so far, most of them women and children—brings her back to the war in Syria. “I lived it and followed its events,” the 40-year-old told Syria Direct.

“There is no difference between a Jordanian, a Syrian, an Egyptian or any other nationality,” she added. “The Palestinian cause is all of ours, and we must respond to it.” Still, as a Syrian refugee in Jordan, she has not participated in any of the demonstrations that have come out in support of Gaza.

Alia believes she is like most Syrians in the country, who prefer to avoid the protests. “It may be because our situation is unstable. We fear anything threatening our lives in Jordan,” she said, as well as “being forced back to Syria after living death a thousand times to escape with our lives.” While “the great losses Syrians have suffered are a basic source of fear,” there is also “ignorance of laws that prevent or allow them to demonstrate,” she added.

Jordan currently hosts 638,760 Syrian refugees registered with the United Nations’ Refugee Agency (UNHCR).

Sami al-Shami (a pseudonym) thinks it is unlikely refugees face specific restrictions when it comes to Gaza protests. “I haven’t read a clear statement barring Syrians from demonstrating,” the young Syrian said, adding that he participated in one pro-Gaza demonstration that came out of the al-Kalouti Mosque during Ramadan.

“There could be a difference between a Jordanian and a Syrian in terms of the right to demonstrate, which is a distinction that exists in any country in the world,” al-Shami added.

Still, the arrest and possible deportation of Abu Salem, al-Ashi and others is entrenching fears Syrians like Alia hold of demonstrating in support of Palestinians in Gaza or freely expressing their political views on other regional issues.

One Jordanian activist, who is taking part in a social media campaign to stop Abu Salem’s deportation, noted “the restriction of freedoms regarding support for Gaza applies to everyone, Jordanians and Syrians, but a Jordanian might get out on bail and be put under a travel ban while a Syrian could be punished with deportation.” She requested anonymity for security reasons.

Kingdom of silence

Following Abu Salem’s arrest, a social media campaign entitled “No to the Deportation of Abu Salem” was launched in an effort to pressure Jordan to reverse its decision, with activists from Jordan and Syria participating.

Relatively few Syrians in Jordan have openly interacted with the campaign, compared with those of other nationalities or outside the country, due to “fear for their lives and future,” the activist said.

The families of Syrians detained in Jordan have also remained silent, dealing with their children’s cases “with extreme caution, fearing they will face deportation, and that the rest of the family could be deported too,” she added.

“The officer threatened me, saying any advocacy action or talk in the media would result in my deportation”

Undisclosed threats from Jordan’s security services could also be behind the families’ silence, Omar (a pseudonym), a Syrian refugee in France, told Syria Direct. Omar was himself arrested as a refugee in Jordan, and described how “the officer threatened me, saying any advocacy action or talk in the media would result in my deportation.” He spoke on condition of anonymity out of fear for his family, who still live in Amman.

In recent years, Jordanian authorities have summarily deported Syrian refugees, including large families, en masse without giving them “a meaningful chance to challenge their removal,” as Human Rights Watch reported in 2017. “Jordan has not assessed their need for international protection,” it added.

There are no official statistics on the number of Syrians deported from Jordan, but “during the first five months of 2017, Jordanian authorities deported around 400 registered Syrian refugees each month,” Human Rights Watch noted.

Despite the ever-present threat of deportation, Omar held that public solidarity with Abu Salem and other Syrian refugees detained in Jordan is necessary. “Jordan takes advocacy campaigns into account and acts in accordance with international law. It understands the pressures on it when the detention is arbitrary,” he said.

Advocacy campaigns, for Syrian detainees in Jordan, are also “proof of your arrest,” Omar added. “Without the campaigns, nobody knows about you, except for when the Red Cross visits your cell and takes your information.”

Both Abu Salem and his Jordanian friend faced “injustice,” Sawai said. However, “the focus is on Atia’s story because of the security situation, and the threat to his life if he is not given the opportunity for resettlement in a third country.”

“All the detainees, of various nationalities, have had their rights violated. But the decision to deport [Atia] is unjust, and we cannot stay silent,” Sawai said. “There is an urgent need to act and apply pressure to stop it.”

This report was originally published in Arabic and translated into English by Mateo Nelson.