A Syrian story: One grandfather’s quest for a quiet life

Mahmoud Ahmad al-Hallaq, a grandfather, carpenter and refugee from East Ghouta living in Lebanon, recalls his time in the Syrian army cooking for Cuban soldiers during the 1973 Arab-Israeli War, and the many twists and turns of his ill-fated quest for a quiet life.

24 April 2023

MARJ, BEKAA VALLEY – All Mahmoud Ahmad al-Hallaq ever wanted was a simple life, far from politics. But over the course of a lifetime that began just two years after the modern Syrian state was established, his country’s turmoil found him time and again, leaving him a reluctant witness to history.

These days, Mahmoud, 75, and his wife Raida Suheil al-Laymouni do not often venture outside Tent 19, their residence in a refugee camp on the outskirts of Marj, a village in Lebanon’s eastern Bekaa Valley. They prefer to stay inside, daydreaming of jasmine, fig and peach trees left behind at their home in Jisreen, a village in the East Ghouta suburbs of Damascus. “Our land was as big as this whole refugee camp,” Raida says.

Mahmoud was born in 1948, two years after Syria gained full independence from France. He grew up in East Ghouta, raised by his eldest sister after losing his parents at an early age.

School never appealed to him, and he did not learn to read or write. Social advancement, in the turbulent Syria of his youth, seemed risky. “You would hear some officer has been executed, this other one was killed, I’d say to myself—good thing I didn’t learn, I don’t want to learn,” he explains, half-joking.

Political intrigue and upheaval plagued Syria in the early years of independence. Mahmoud tried his best to ignore it. “I remember we had Gamal Abdel Nasser for a while,” he says, referring to the brief period when Syria and Egypt became the United Arab Republic, from 1958 to 1961. “I have seen three changes of president in my life.”.

His count falls a bit short: From 1949 through the 1960s, Syrians witnessed seven military coups. In 1970, Hafez al-Assad’s coup became the definitive one, and he ruled Syria until his death in 2000, when his son Bashar al-Assad took over.

Mahmoud’s memory fades a bit when it comes to numbers. Counting his grandchildren, he confidently states “I have six,” prompting Raida to burst into laughter. “What do you mean six? Hanan has four, Haifa has four, Huda has three, Sada has four,” she says, counting them off before Mahmoud interrupts. “Anyway, when I talk on the phone with them, their mother tells them ‘talk to your grandpa’ and they know I’m the grandpa,” he concludes.

Raida Suheil al-Laymouni (left) and Mahmoud Ahmad al-Hallaq (right) in their tent in a refugee camp just outside Marj, a village in Lebanon’s eastern Bekaa Valley, 24/1/2023 (Alicia Medina/Syria Direct)

Mahmoud has seven children, all from a previous marriage with a woman who died from a prolonged illness before the war. Some of his children are still in Syria, while the others live in Turkey and the Netherlands. Like many Syrian families, war has separated them. Mahmoud has not seen any of his children for eight years.

War and the Cubans

Mahmoud’s memory sharpens as he remembers his time, “three years and 11 days,” in the Syrian army in the late 1960s. He was conscripted at 19, and spent his mandatory military service as a cook. “When I first joined, it was just 5 Syrian pounds per month during my mandatory service, and then I got 250 pounds, which was good at the time,” he explains.

After these three years, he went back to his civilian life, but in 1973 he was called up once again to join the military, as a reservist. That year, Syria and Egypt led a surprise attack against Israel in an attempt to regain territories the Israeli army captured during the Six-Day War in 1967, including Syria’s Golan Heights. The conflict became a proxy war within the Cold War, with the United States backing Israel and the Soviet Union backing the Arab countries. Israel claimed victory in three weeks, in a defeat that would shape the region for years to come.

Unbothered by geopolitics, for Mahmoud the main takeaway from the war was the Spanish he learned during the conflict. Cuba was one of several countries that dispatched soldiers on the ground to join the fight against Israel, and he became their cook.

He remembers being impressed by their organization. “The Cubans had 100 cars, they would park them so organized, and they all dressed the same,” he says. “They were very organized.” In addition to cooking for the Cuban soldiers, he would sometimes assist them with other tasks. “I would give them information on the region: that city is called this, that village is that, etcetera,” he explains.

Mahmoud, who never engaged in active combat, remembers the Cubans stayed with his unit for three months, during which he learned some expressions in Spanish that he still remembers. “I would point at a teacup and ask them ‘how do you call this in Cuban?’ They told me ‘taza te.’ I learned how to ask them for things, ‘dame [give me] something,’” he explains with a smile.

He befriended one Cuban soldier named Wilfredo. “By the end, we could understand each other pretty well. For instance, he would point towards a prison and say ‘malos’ [bad guys],” he remembers. But sometimes, when it suited him, Mahmoud would pretend not to understand. “Wilfredo would tell me, ‘Mahmoud, dame cigarreta [give me a cigarette],’ and I pretended I didn’t get what he said.”

Cuban tobacco, despite its worldwide fame, held little appeal for Mahmoud. “Their Cuban cigarettes were so strong they weren’t good—I always choked,” he says, grimacing in disgust.

At one point, the Cubans—unaware Mahmoud could not read—put him in charge of a checkpoint, instructing him to only let cars through if they had a military permit. “I didn’t know how to read, so the people in the cars would show me a piece of paper and I was like, ‘God be with you, you can pass,” he recalls, laughing almost to the point of tears. When his superior furiously demanded to know who had let all the cars pass, Mahmoud brushed it off. “The Cubans liked me anyway.”

‘Life was enough as it was’

After his stint in the army was over, Mahmoud went back to his passion: wood carving, a trade he learned with his uncle starting at 15 years old. Soon enough, he opened his own carpentry workshop in East Ghouta producing everything from furniture to delicate wood inlays.

“I loved that job. I worked on my own with the wood, that was my hobby. Educated people would come to watch me work and learn,” he says, beaming with pride.

He had clients from other regions like Darayya or Kafr Sousa. “People would say ‘there’s a guy in East Ghouta that does work that nobody else can do,’ that was me,” he explains. In his workshop, he found peace. “People would come into my shop, grab a cup of tea and stay for an hour or two,” he remembers.

At some point, he says the son of the local mukhtar offered him the opportunity to travel to Switzerland to showcase his work, but he did not see the point of leaving his village. “I was happy, I didn’t want more or less. Life back then was enough as it was,” he says.

Today, one of the few belongings in the tent Mahmoud and Raida share is a little carved wooden piece they bought in Lebanon. “This is like what he used to make. His were much better quality, but were something like this,” Raida explains, holding it up.

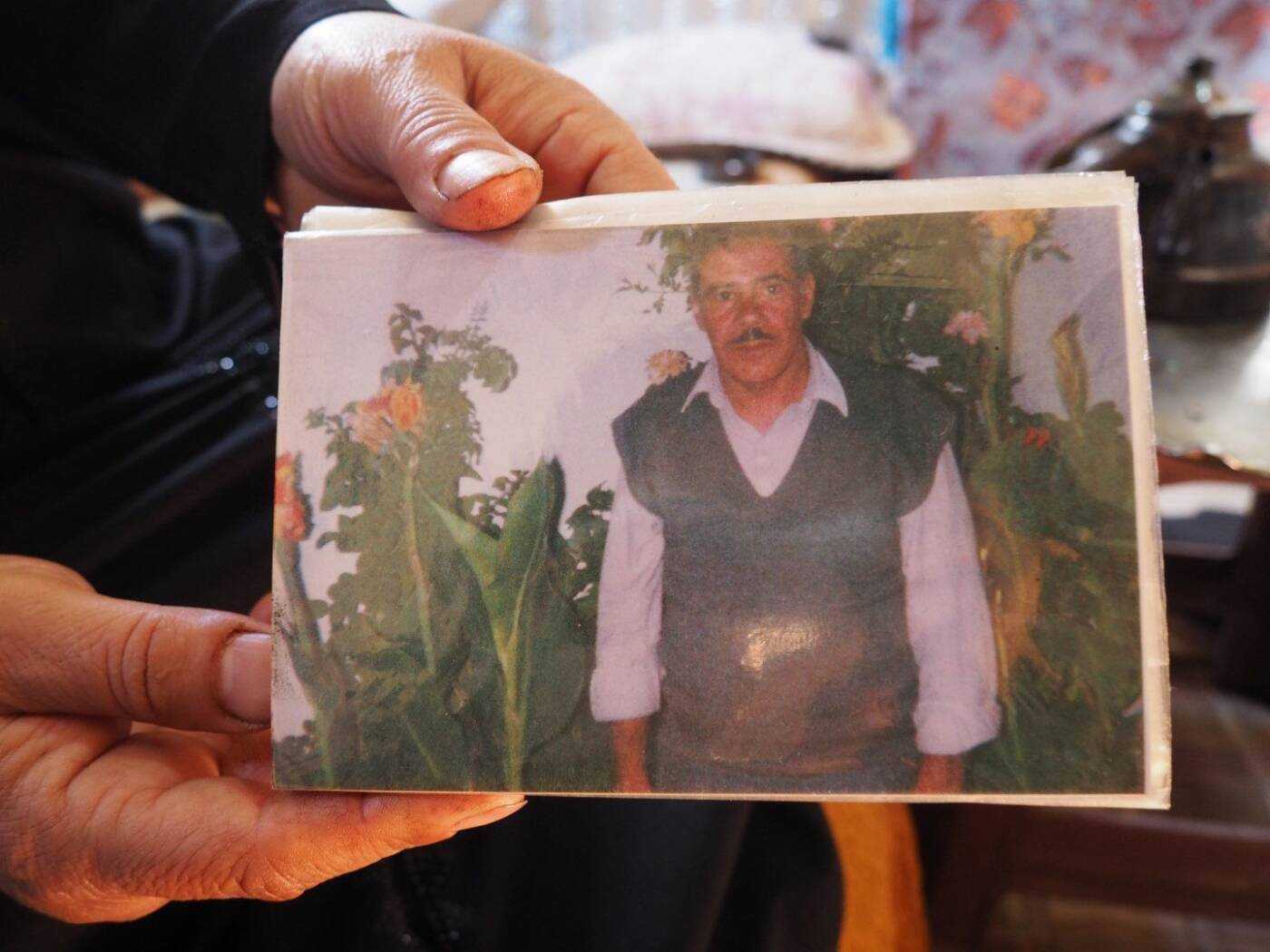

All of Mahmoud’s wooden art was left behind when they fled death and siege in Syria in 2014. The only memento they brought to Lebanon was a photo album filled with a dozen photos, showing old, happier days in Jisreen.

Raida holds up a photo of a younger Mahmoud posing in his garden in Jisreen, East Ghouta. It is one of the few items the couple brought with them when they fled Syria for Lebanon in 2014, 24/1/2023 (Alicia Medina/Syria Direct)

Flipping through the album’s pages, Raida and Mahmoud reminisce about their life before war. “The nicest thing in East Ghouta was Tal al-Dahab. There were trees, a river, flowers—we would go on the weekends and cook mashawi [grilled meat] with friends,” Mahmoud explains.

In one picture, a younger Mahmoud poses in front of his garden in Jisreen. “We had many trees, mint, peaches, figs, zucchinis, jasmine, thyme,” he remembers. “We would eat from the garden,” Raida adds. “When any neighbor came, we would eat together, or if we visited them we would pick cilantro, parsley, beans, onions and would leave their house with a bag full of vegetables.”

Raida and Mahmoud are still in touch with some of their neighbors who stayed behind in Jisreen, but do not mingle much in the camp where they live now and barely know the families in the other tents.

Under siege

The simple, fulfilling life that Mahmoud and Raida remember in their village was torn apart in 2011, when popular protests against the rule of Bashar al-Assad were met with a bloodbath. The uprising morphed into a conflict that has since killed at least 306,887 civilians, according to the United Nations.

At the beginning of the conflict, they tried to stay on the sidelines. “We never had a problem or security issue with the regime,” Raida says. “I didn’t get interested in the protests. Some people wanted the Baath [Party, led by Assad], some people wanted freedom. Everyone was asking for something. Me, I didn’t get close to any side. I’m on my own,” summarizes Mahmoud.

But the reality on the ground caught up to them. Their idyllic East Ghouta became a battlefield in the early days of war, and in 2013 the regime imposed a siege that lasted until 2018. “Not a drop of water or bread entered Ghouta, if someone was able to give you a cup of tea, that was a miracle,” Raida remembers. Her weight fell from 100 to 60 kilograms, she says, and her husband’s fell to around 50 kilograms. “You could hug Mahmoud’s waist with two hands.”

In 2014, after surviving four years of war and siege, they escaped through a tunnel dug from East Ghouta to a nearby town, Barzeh. They took nothing with them but the photo album, a book of memories frozen in time. That year, they made it to Lebanon. They have been in a plastic and wood tent ever since. Lebanese authorities ban permanent construction materials in Syrian refugee camps.

A year and a half after they arrived in Lebanon, their house in Jisreen was destroyed by a rocket. Mahmoud still hopes to return one day—he wants to rebuild. “I have hope to return, so I can go and fix my house. A stranger is not safe in any country,” he says. “Lebanon is not my home.”

Raida feels less confident. “I have no hope to return,” she says. “We have no security issues with the regime, but I’m afraid if we return we will starve. People struggle to eat today in Syria.”

Still, “there is nothing more beautiful than Syria,” she adds. “An hour in Syria is worth a lifetime,” Mahmoud agrees.