Detained, deported, disappeared: Assad’s critics face ‘nightmare’ in Lebanon

As Lebanon presses forward with mass deportations of Syrian refugees, those openly involved in opposition activities against the Assad regime face a growing danger.

9 February 2024

TRIPOLI/BEIRUT — In Lebanon’s northern city of Tripoli, Abdullah’s phone rings off the hook. Dozens of callers ask about the whereabouts of his relative, Yassin al-Atar. His voice is hoarse, his eyes bloodshot. Since January 25, the day Abdullah heard Yassin would be deported, he has barely slept.

Abdullah (a pseudonym) is working around the clock—speaking with lawyers, journalists and human rights organizations—to try to prevent 27-year-old Yassin from being deported to Syria, where he feels certain he “would be killed.”

Yassin’s is one of hundreds of deportation cases against Syrians in Lebanon in recent years, as the country’s government presses forward in its efforts to induce refugees to leave, whether “voluntarily” or by force. Lebanon currently hosts approximately 1.5 million Syrian refugees.

In October 2022, the Lebanese government resumed what it calls a “voluntary return” plan, aiming to send back 15,000 Syrian refugees per month under the contention that Syria is safe for return. Since then, the number of Syrian refugees deported from Lebanon has spiked.

Last year, the Access Center for Human Rights (ACHR), a human rights organization based in Beirut and Paris, documented 1,080 arbitrary arrests and the deportation of 763 Syrians. In 2022, just 154 Syrians were deported, and 59 in 2021, according to ACHR.

“Syria is not safe for returns,” Human Rights Watch (HRW) researcher in Lebanon, Ramzi Kaiss, told Syria Direct. In 2023, HRW documented the arrest, forced conscription and torture of multiple deportees once back in Syria.

While all deportees face risks, the danger is enormous for those, like Yassin, who have been openly involved in opposition activities against the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

When Yassin was just a teenager, he took part in mass pro-democracy and anti-regime protests that erupted in his city of al-Qusayr, in Syria’s central Homs province, at the start of the 2011 revolution. Yassin’s father and two uncles were also involved in different forms of anti-regime activism, including organizing demonstrations, working for various media outlets to document human rights violations and helping injured people access treatment outside Syria.

Assad responded brutally to the demonstrations, slaughtering hundreds of protestors in the weeks and months before the uprising turned to war. Syrian security forces have arrested and tortured, sometimes to death, those who helped organize campaigns against the ruling regime.

Yassin’s father was arrested by Syrian security forces in 2011, taken from his home in al-Qusayr. His family has not heard from him since. “We don’t know if he’s alive or dead,” Abdullah told Syria Direct.

In 2012, about a year after his father was taken, Yassin fled his Homs village, with his mother and six siblings, for the Lebanese border town of Arsal.

“If Yassin went to Syria, we wouldn’t see him again,” Abdullah said. “It’s very dangerous. They would torture him, abuse him and likely kill him.

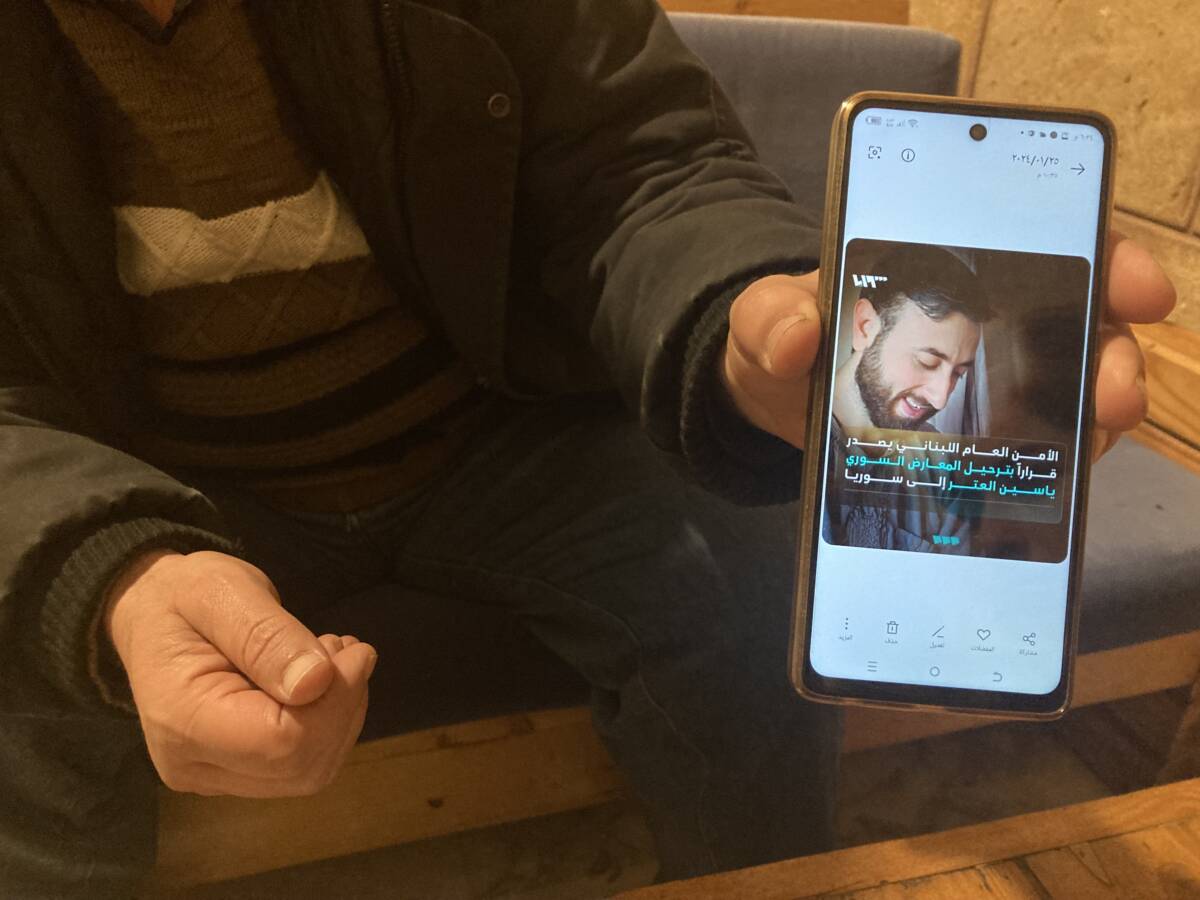

Abdullah (a pseudonym), shows a picture of Yassin al-Atar, his relative facing deportation from Lebanon, at a cafe in Tripoli, 31/1/2024 (Hanna Davis/Syria Direct)

Relatives and former neighbors in al-Qusayr told Abdullah that Syrian intelligence agents came to collect information on Yassin’s activities in Lebanon on January 25, he said, the same day he was given the deportation order. He also heard that security forces demanded the entire family return to Syria.

Yassin has been detained at Lebanon’s General Security branch since December 19, where he has been able to call Abdullah periodically. In the latest call, Yassin told Abdullah he would start a hunger strike on February 9 to protest his return to Syria.

Skirting the law to deport

As Lebanon forcibly deports Syrians by the hundreds, there are many cases like Yassin’s, Muhammad Sablouh, a human rights lawyer who is representing him, told Syria Direct at his office in Lebanon’s northern city of Tripoli.

Every day, Sablouh said he hears of roughly 10 Syrians who are deported. “I’m sure many of these cases aren’t being heard or reviewed [prior to their deportation],” he added. The stack of legal papers on his desk grows high.

Muhammad Sablouh, a Lebanese human rights lawyer, works at his office in the northern city of Tripoli, 31/01/2024 (Hanna Davis/Syria Direct)

In one such case, Sablouh said the Lebanese military deported 33-year-old Raafat Abdel Qadar Faleh—a defector from the Syrian military— to Syria in early January. Raafat’s parents contacted Sablouh for help. Defectors from the Syrian military have been found subject to arrest, detention, enforced disappearance and torture by the Syrian regime.

Raafat is from Busra al-Sham, a town in the former opposition stronghold of Daraa in southern Syria. In 2018, after Damascus retook control of the province, Raafat was called to join the Syrian military, his uncle told Syria Direct in messages sent through Sablouh.

Rafaat enlisted, but defected in 2019, a year later, largely due to atrocities he witnessed during intense fighting between the Syrian military and opposition groups in the Aleppo countryside, according to his uncle. Shortly afterwards, Raafat fled to Lebanon with his wife and children.

On January 10, Raafat was stopped at the al-Madfoun checkpoint, between Lebanon’s Jbeil and North governorates, and arrested by Lebanese military personnel. At the end of the month, Rafaat’s uncle heard from a relative in Daraa that Syrian military intelligence had asked for information about him. During the conversation, intelligence officers told the relative that Rafaat would be handed over to Syrian authorities, he said.

ACHR reported that the Lebanese army arrested 15 Syrian refugees on January 9 and 10 at the al-Madfoun checkpoint and deported them immediately to Syria through the Wadi Khaled border crossing. A Lebanese man who was driving the microbus Rafaat was in on January 10 confirmed to Sablouh that he was among those arrested. There has been no news of him since.

Sablouh has filed a missing persons complaint and a complaint about Raafat’s detention by the Lebanese army. “The Lebanese army has no right to deport people. This is a violation of the law,” Sablouh said. The public prosecutor has mostly ignored the complaints, Sablouh said, and told him he was “busy.”

The deportation of any Syrian refugee violates Lebanon’s obligations as a signatory to the United Nations Convention Against Torture. It also runs contrary to the international law principle of non-refoulement, or a country’s obligation to not forcibly return people to countries where they would face torture, persecution or other forms or irreparable harm.

Summary deportations of Syrians, carried out by the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF), also appear to violate Lebanese law, under which deportations must be conducted through a judicial authority, or “in exceptional cases,” by the decision of the General Director of General Security based on an assessment of individual circumstances.

Cases of summary deportations documented by HRW include Syrians whose residency papers had expired were deported without a judicial decision or opportunity to challenge their removal, HRW’s Kaiss told Syria Direct.

Since 2015, Lebanon has imposed residency regulations that have made residency renewals an “inexplicably difficult task,” Kaiss added. The vast majority, or around 83 percent, of Syrian refugees in Lebanon do not have legal residency, according to the UNHCR.

In response to HRW inquiries about the legality of summary deportations by the army, the LAF responded that it was implementing the Higher Defense Council’s April 2019 decision to deport Syrians who entered Lebanon irregularly after that date.

‘Arbitrary’ deportations

Yassin’s trouble with Lebanese authorities began in 2017, when he was arrested on a terrorism charge and ultimately sentenced to 10 years in prison. At the time of his arrest, he was 20 years old and living in Arsal, on Lebanon’s northeastern border with Syria.

Lebanon’s army has periodically raided refugee camps in Arsal and arrested hundreds of Syrians searching for fighters with armed groups such as the Islamic State (IS) or Jabhat al-Nusra. In the summer of 2014, the Lebanese army and Hezbollah clashed with IS and Jabhat al-Nusra fighters in Arsal. The fighting killed 69 civilians, fighters and soldiers.

Abdullah insists Yassin was not involved with any armed group. “He was a humanitarian, a student, he was young,” he said. Yassin was not arrested during a raid, but while undergoing a military security check to travel from Arsal to Tripoli.

Sablouh said that many Syrians in Lebanon have been wrongly accused of terrorism, as civilians were intermixed with fighters in border towns like Arsal and insufficient efforts were taken to distinguish between each case.

Seven years into his 10-year sentence, Yassin paid $3,400 for an early release from prison on December 19. He was then transferred to General Security, where he received his deportation order around a month later.

Sablouh said General Security is treating deportation cases in a “very arbitrary way,” often without judicial review. In some cases he has seen, Syrians were forced to consent to deportation, he added. He said he has not been allowed to visit Yassin at General Security. Syria Direct was not able to directly contact Yassin.

The United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) in Lebanon, the body responsible for protecting, assisting and advocating for refugees in the country, can do little to intervene in deportations. Sablouh accused UNHCR, like Lebanese judges, of “not taking the deportation cases seriously.”

UNHCR Lebanon spokesperson Lisa Abou Khaled said the agency takes reports of deportation “very seriously” and advocates for the respect of international law and the protection of refugees from refoulement. She told Syria Direct UNHCR has raised the issue of deportations with authorities and “will continue to do so.”

Danger grows

Under the growing threat of deportation, life is increasingly precarious for Syrian opposition activists in Lebanon, whose public profiles leave them particularly at risk.

In 2019, Lebanon’s Higher Defense Council issued several decisions, ordering the summary deportation of those entering the country irregularly and cracking down on Syrians working without authorization, which increased pressure on Syrian refugees in Lebanon. The result has been “a host of coercive regulations and ad hoc practices designed to ensure Syrian refugees will eventually feel like they have no choice but to return to Syria,” according to a 2023 HRW report.

One longtime activist, who goes by Abu Ali, has mostly ceased his political activism and is laying low as the Lebanese government cracks down on Syrians. Sitting at a café in Beirut this month, the 50-year-old drew one hand across his neck in a slashing motion. “I would be killed [upon return to Syria],” he told Syria Direct.

Abu Ali spread his hands wide to display his fingers, explaining that they were all broken when he was tortured in a Syrian prison in 2012. He was imprisoned in Syria five times due to his activism against the Assad regime: twice before the 2011 revolution and three times afterwards, he said.

In 2013, Abu Ali fled his hometown of Salamiyah, in Syria’s central Hama province, for Lebanon. During the first few years in Lebanon, Abu Ali and his activist peers were able to continue their conversations about the future governance of Syria and maintain a social media presence in Beirut. They had a degree of protection under Lebanon’s Progressive Socialist Party, led by Walid Jumblatt, a vocal critic of the Syrian government, he said.

However, around 2015, the tide turned as pressure began to ramp up on Syrians in the country. Abu Ali shifted his efforts to humanitarian support, he said.

Sitting beside Abu Ali, Haitham*, a 28-year-old Syrian activist, said navigating the threat of deportation has reshaped his life in Lebanon. He mostly stays close to home, careful to not venture too far into the wrong neighborhoods or be caught at one of the army’s many checkpoints set up around the capital.

At the start of the Syrian revolution, Haitham worked in Damascus for media outlets critical of the regime. He is certain he would be arrested if he is sent back. He attempted to register with UNHCR in 2015 and get more protection due to his situation, but said his request was denied.

Now, Haitham lives in a state of almost constant anxiety. “There’s a fear to walk at night, to go out. We are dead [if they catch us],” he said.

‘Lebanon is a nightmare’

For many Syrians, the pressure in Lebanon has become unbearable. Naama al-Alwani, 32, who was a vocal critic of Assad through her work as a journalist in Homs before fleeing to Lebanon, said that many Syrian activists, like herself, have now left.

“They’ve almost disappeared,” she told Syria Direct. “It’s very hard to speak of the Syrian revolution inside of Lebanon.”

Naama was imprisoned in Syria for eight months, between October 2013 and June 2014, due to her activism. A month later, she fled. “We knew, from the beginning, it would be difficult to be an activist in Lebanon. But we didn’t have another option,” Naama said. “We’d started in Syria, we weren’t afraid of the regime, so we continued to not be afraid of anyone.”

In Tripoli, Naama continued to work as a journalist, and was active on social media. However, a few years after she arrived, she began to receive threats from members of Hezbollah, a Lebanese armed group closely allied with the Assad regime. Naama received sexual insults, death threats and threats to her family, she said. As a result, she restricted her movement around the country and shut down all of her social media accounts.

Naama also said she faced frequent intimidation and harassment at Lebanon’s General Security each time she went to renew her residency. Her mother is Lebanese, which entitles her to a three-year residency, but she was given eight-month renewals instead, she said. Lebanon’s laws require citizenship to be passed from the father—a law common throughout the region, including in Syria.

So in 2019, Naama found help from Reporters Without Borders, who helped her apply for a visa to travel to France, where she arrived in 2021. “I left Lebanon as fast as I could,” she said.

“Lebanon is a nightmare for me,” Naama said. “But if I go to Syria, I’ll face death, as applies to every activist and journalist [against the regime].”

She noted that the tone of activism among many of her fellow activists still in Lebanon has turned to the economic crisis in Syria, rather than political activism against the regime. Many activists would like to distance themselves from trouble, she added. “People have different priorities now.”

“The situation in Lebanon is getting harder, year after year, making it even more difficult for Syrians to handle,” Naama stated.

Waiting for news

Yassin’s relative, Abdullah, has pinned all of his hopes on the media to spread awareness of Yassin’s deportation case and help get him released. Media attention is often the only way to prevent a deportation case, Sablouh said. But as the days pass without updates from Yassin, hope is wearing thin.

At first, Abdullah tried to keep the news of Yassin’s deportation order away from the 27-year-old’s mother. She lives with his four sisters in Tripoli, and had been eager to see her son again after his release from prison in December.

Still, the news leaked in: buzzing Facebook notifications and social media posts about Yassin, and the imminent danger he faces. There is little she can do but wait.

“His mom and sisters, they’re all waiting,” Abdullah said. He breathed a sigh, reaching for the box of tissues to dab away a tear. As of the time of publication, there were no updates on his case.

In his latest call, Yassin told Abdullah he would start a hunger strike on February 9 to protest his return to Syria.