Awaiting reconstruction: For displaced residents of Damascus’ Jobar neighborhood, no return until redevelopment

Five years after residents of Damascus’ Jobar neighborhood were displaced, they are still denied return. The release of Development Plan 106 last June has only heightened fears and uncertainty about the future of their property.

24 April 2023

DAMASCUS — Five years after Syrian government forces retook control of opposition-held areas of Damascus and its eastern suburbs in March and April 2018, former residents of the Jobar neighborhood are still barred from returning.

“Entering the neighborhood is completely forbidden,” 60-year-old Abu al-Ezz Moumina said. Even the cemetery is off limits. “Residents of Jobar cannot bury their dead there,” he told Syria Direct.”

Moumina left Jobar in 2013, after the neighborhood became a “military flashpoint” as battles between government and opposition forces intensified. He rented a house in the government-controlled Damascene suburb of Jaramana, where he still lives.

When opposition fighters evacuated the Damascus suburbs, including Jobar, for northwestern Syria under the 2018 settlement agreement, Moumina tried to return to the neighborhood and access his home. He was prevented from entering “even for the purpose of visiting,” he said.

For years, Moumina has lived in the hope of returning home. But since Damascus province released a detailed development plan in June 2022 for six real estate areas in and around the capital, he fears that his property is under threat. Particularly concerning to him is that residents like himself will not receive alternative housing, as Damascus Director of Development and Urban Planning Hassan Traboulsi told local media when the plan was issued, but rather shares in the new developments as a form of compensation.

A vague development plan

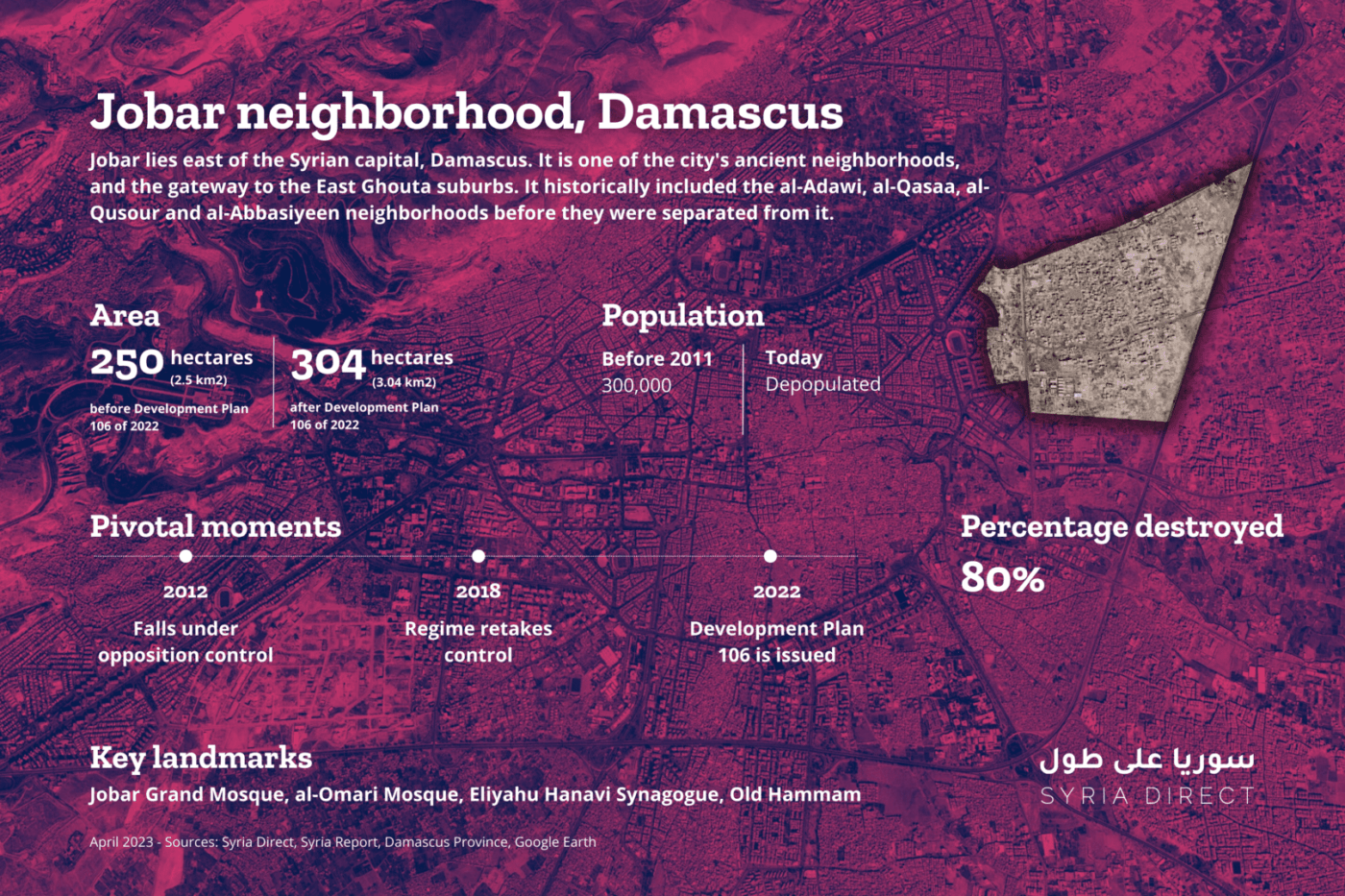

Jobar is located in northeast Damascus, bounded by the neighborhoods of Bab Touma, al-Qasaa and al-Tijara to the west, Qaboun to the north and Zamalka to the east. Between 2012 and 2018, it witnessed battles between government forces and opposition factions, until the latter took control of the neighborhood. Most of its remaining residents were subsequently displaced, and at least 80 percent of the neighborhood was left in ruins.

Under Development Plan 106 of 2022, Damascus province aims to reclassify six real estate areas—Jobar, Qaboun, Masjid Aqsab, Arbin, Zamalka and Ain Tarma—as areas “under urban development.” Previously, these areas were classified as protected zones, agricultural areas or residential expansion zones.

Development Plan 106 was issued following a study of Jobar and its surroundings conducted by Damascus province. The plan adds portions of adjacent areas to Jobar, increasing the area of the mostly destroyed neighborhood from 250 hectares to 304 hectares. Jobar is subject to Planning and Urban Development Law 23 0f 2015, Traboulsi told radio station Sham FM last year.

The redesignation of these areas as “under urban development” in accordance with Syria’s Urban Planning Law—Decree 5 of 1982, amended by Law 41 of 2002—means that residential, commercial and service construction is permitted under the new detailed development plan.

Under Syria’s Urban Planning Law, a detailed development plan determines “all the planning details for a network of main and subsidiary roads, pedestrian walkways and public spaces, as well as all details for land use and does not contradict the general development plan or construction codes,” Wissam al-Sali, a Damascus-based specialist in architecture and sustainability, told Syria Direct.

The incorporation of Jobar and the other areas included in the plan “will inevitably lead to the full or partial seizure of some owners’ properties in the Jobar area, as development will require existing roads to be expanded and new roads, gardens, schools and other public facilities to be built,” a Syrian lawyer and expert in real estate ownership issues explained to Syria Direct, asking to remain anonymous for security reasons.

After the detailed development plan was issued and approved by the Ministry of Housing last year, it was displayed on the Damascus Provincial Council’s bulletin board, Traboulsi said at the time. Residents of the neighborhood had one month to review it and submit their objections in person, which would be passed on to a regional technical committee headed by the governor for review.

Infographic | Jobar, Damascus 24/4/2023 (Syria Direct)

“Giving citizens a short time frame to raise objections or prove their ownership is not enough. It is difficult to prove ownership within this period, especially as most of the residents of areas included in the new development plan may be wanted [by the security services] or displaced,” the lawyer said. Given objections must be submitted in person, it is virtually impossible for most refugees and displaced people–especially those residing in opposition areas–to contest redevelopment plans.

A number of Jobar’s former residents have tried to object to the detailed plan for their city’s redevelopment since it was displayed in the Damascus province’s headquarters last year. But as the neighborhood is empty and its displaced residents do not have enough information about the future of their rights under the plan, “most of those objecting do not know what they are objecting to,” Moumina said.

Architecture and sustainability specialist al-Sali attributed the weakness of community action in opposition to—or in favor of—the plan to “the absence of a civil action mechanism, given many years of systematic oppression that has prevented any civil movement from being formed.”

In his view, the development plan should have “taken into account this inherent fragility, and included mechanisms for communicating with residents inside and outside the country,” al-Sali told Syria Direct. This approach would have reflected “a duty rather than a favor to residents.”

While urban planning head Traboulsi initially expected the final decree approving the detailed development plan to come within six months, it has yet to be issued nearly one year later.

“The delay in implementing the decision is not as important as the way urban development decrees deliberately remove all residents from their damaged and destroyed homes and turn them into hectare shares in the development plan,” al-Sali said. “Damascus province’s plans have become a tool for deliberately displacing the owners of property and land, despite recognizing their rights,” he added.

Al-Sali criticized the release of a plan of this size “without any mechanisms for engaging with residents, especially in the post-war construction phase, while many Syrian academics are being excluded from the planning and implementation phases and there is no clear vision of the current situation in Jobar.”

A violation of property

While a large share of residents from Jobar were displaced to opposition areas or abroad, others took refuge in government-controlled areas. Those who remain in Damascus live in rented homes in the capital and its outskirts, where living conditions are deteriorating and rents are high.

Manal Ajaj, 46, told Syria Direct that she pays SYP 350,000 (approximately $44.58 according to the current black market exchange rate of SYP 7,850 to the dollar) each month for a residence in Jaramana. The average monthly salary of a public sector employee in Syria is around SYP 100,000 ($12.73). She described her housing as “poor, compared to my home in Jobar,” which she was forced to leave in 2013. She does not know what has become of it since then.

Former residents of Jobar object to not being permitted to return to their homes, unlike those from other areas that Damascus regained control over, Ajaj said. They also criticize the fact that the entire neighborhood is subject to the development plan, including real estate. “Damascus province has prevented us from returning to the area, as well as from selling or buying [property] within it,” she said.

In this context, al-Sali wondered: “Is the whole neighborhood really in need of a new plan, or only part of it? Is the whole infrastructure damaged?” He said the provincial government had established a border around Jobar, “which is one of the most infuriating violations for residents, as it is a stone’s throw away but remains off limits to most of them.” Syria Direct was not able to independently confirm the nature of the security restricting access to the neighborhood.

Although Damascus has not officially announced that residents of Jobar are barred from returning, local media reported in 2021 that the Damascus Provincial Council had made an “unannounced” decision stipulating that residents of the neighborhood be permanently prevented from returning, under directives from the security services.

Ajaj still has the ownership documents for her home in Jobar, but members of her family lost their documents when they were displaced by battles raging in the neighborhood. Still, even with her ownership documents, “I fear our rights will be lost and that we won’t be able to recover them because of the development plan,” she said. “Perhaps our grandchildren will get our rights!”

In Jobar, Ajaj and her family owned homes and commercial spaces. Today, they live off of “aid and God’s mercy,” as she put it. “My brother owned a shop in Jobar. Now he is 50. What work can he find at that age?”

The desire to return

If Damascus province proceeds with the development plan for Jobar, then it must “set a date and determine the timescales for construction as soon as possible so that people can get their properties,” Ajaj said. She added that “the province has [so far far] abandoned the plan and neglected the issue, showing no regard for the pain and suffering of the residents.”

Abu Amjad, 60, agreed with Ajaj. “Is what happened in Jobar a form of collective punishment?” he wondered. “Most of the neighborhood is included in the development [plan], so how will it be redeveloped? And how much of our original property will remain?”

Abu Amjad lives in rented accommodation in Reef Dimashq, for which he pays SYP 350,000 (approximately $44.58) a month. According to him, his home in Jobar could be lived in “following minor restoration,” but he is not allowed to return to it.

“The development plan is not supposed to be a large piece of paper setting out the areas and boundaries of the land; rather it should be a way of communicating these [engineering] symbols directly to the owners of these properties, without any middlemen, holding companies or real estate companies,” al-Sali said.

“Damascus province should have begun the development of Jobar through small planning clusters rather than starting to develop the neighborhood and surrounding areas as a whole, an area measuring 3 million square meters,” he added.

“Converting a home into a hypothetical share of the development is particularly violent to a fragile and homeless community,” he concluded. It is difficult to explain to the neighborhood’s displaced residents that “none of their houses will be the same as they were before, or in the same neighborhood and quarter.”

This report was originally published in Arabic.