Denmark pushes Syrians to return to ‘safe’ Latakia and Tartus

After deeming Damascus and Reef Dimashq safe for return in 2019, Denmark is now reassessing the right of Syrians from Latakia and Tartus to stay in Denmark on the grounds it is safe for them to go back to Syria.

29 March 2023

ATHENS – Danish immigration authorities are reviewing the status of about 100 Syrian refugees from Latakia and Tartus in Denmark, after designating both provinces safe for returns, according to the Danish Immigration Service.

Refugees from both provinces who were granted temporary protection status in Denmark due to generalized violence are now at risk of losing their residence permits and being compelled to stay at “return centers” indefinitely, flee to a third country or go back to Syria.

The move comes nearly four years after Denmark designated Damascus and Reef Dimashq provinces safe for return, a decision at odds with European and international assessments. Hundreds of families had their residence permits revoked as a result, but most were restored on appeal.

On March 17, the Refugee Appeals Board ruled on the first two cases of two Syrian families from Latakia affected by the new designation of Latakia as safe. Immigration authorities had revoked their residence permits on the grounds it was safe for them to return. The judicial body ruled in their favor and granted them refugee status based on individual risk. However, the Appeals Board’s ruling in both cases confirmed the Immigration Service’s assessment and held that Latakia is generally safe for returns.

This means that now Syrians from Latakia “can only retain their residence permit if they have individual reason to fear persecution,” said Eva Singer, head of the Asylum Department at the Danish Refugee Council, an independent body that offers legal services to refugees.

The Appeals Board, an independent quasi-judicial body, has not yet “taken a stance on the Tartus province,” a source from the Danish Immigration Service told Syria Direct, but it is expected that the board will take a similar decision as with Latakia.

Syrians with temporary protection status in Denmark must renew their residence permits on a yearly basis. As the cases of Syrians from Latakia and Tartus come up for review, migration authorities’ designation of the provinces as safe increases the likelihood that their permits will be revoked, though it is possible to appeal.

The Immigration Service could not provide an estimated total number of Syrian refugees from Tartus and Latakia in Denmark, but the cases of 100 individuals from those provinces are under review “in connection with the expiration of the [one-year] temporary residence permits.”

‘Fear is sown in our hearts’

One of the cases under review is that of Fayez Ahmad al-Sheikh. The 54-year-old Syrian fled Latakia in 2014, received temporary protection status in Denmark and later brought his wife and two children through family reunification. Their status came up for review almost a year ago, and given the recent designation of Latakia as safe, al-Sheikh is deeply concerned.

In his most recent interview with migration authorities, al-Sheikh told them that he was sought by the Syrian regime. “My business partner’s father was detained and killed by the security forces, and after I fled Syria, they came to my mother’s house asking for me,” al-Sheikh said.

Al-Sheikh, who currently works part time in a restaurant, was shocked that Danish authorities designated Latakia safe for returns. “How is Latakia going to be safe if it is a lawless place where someone can be detained and killed and you can’t do anything about it?”

Returning to Syria is not an option, he said, even if the immigration authorities revoke his family’s residence permits. “There’s no way we can return. In Latakia we are threatened, we are nothing, we have no voice there,” he said. Knowing that the government of the country where he has found refuge sees the province as a safe option, “fear is sown in our hearts,” he added.

Khaled Barkat Qadri also said returning to Syria is not an option. This month, Danish authorities reassessed the 55-year-old’s residence permit, and told him they will decide to extend or revoke it within the next six months. “If the migration authorities reject me, I will go to the Appeals Board. If I am rejected, I prefer suicide to return,” he said.

Before making his way to Denmark, Qadri fled Latakia for Turkey in 2013, after he was warned that the security services were after him. “My sister told me they came to our parents’ home and they were asking for me,” he said. “If the regime is asking for you, you know what that means.”

Over the past 11 years, Syrian regime forces have been responsible for the enforced disappearance of 95,696 people and the death of 200,291 civilians, according to the Syrian Network of Human Rights (SNHR).

Dubious results

Denmark’s latest designation of Latakia and Tartus as safe for return follows in the footsteps of its similar 2019 assessment of Damascus and its countryside. The earlier designation overturned the lives of hundreds of families for years, and only a very small number of Syrians returned as a result of their residence permits being revoked.

According to the Danish Return Agency—the body in charge of the return of foreign nationals without legal residency—as of July 2022, only 16 Syrians from Damascus and Reef Dimashq who had their residency revoked left Denmark.

Currently, 33 Syrians who lost residency are staying at return centers, according to immigration authorities. There, they are not allowed to work, must check in with the police several times per week and have to request authorization to spend two nights outside the center every two weeks. Breaking these rules may lead to a jail sentence.

“They are not marching people on planes because they can’t do that. These centers are a way to coerce them to reconsidering because people can’t live in dignity. These centers are designed to push people to consider returning,” said Nadia Hardman, a researcher in the Refugee and Migrants Rights Division at Human Rights Watch (HRW). It is “a shameful way to treat people that have come to one of the most devastating conflicts in recent times,” she added.

Danish police have also issued warrants for 76 Syrians whose whereabouts are unknown, meaning that they likely fled to a third country and did not inform Danish authorities. In August 2022, a Dutch court ruled that Syrians who lose residency and flee Denmark cannot be automatically returned because it could not be assumed that “the prohibition of inhuman treatment is respected by the Danish authorities.”

But most Syrians impacted by the 2019 designation regained their right to stay in Denmark after appealing. From June 2019 to March 2023, the Appeals Board overruled the revocation of residence permits in 54.7 percent of cases and sent 12 percent of cases back to the immigration authorities for additional review, according to data the Board provided to Syria Direct. In 32.5 percent of cases, the body upheld the Immigration Service’s decision to revoke or not extend residency.

Given this high rate of overturns, legal experts question the motivation of Danish authorities in expanding the areas they consider safe in Syria. “It’s a bit difficult to understand why the Danish Immigration Services keep on making decisions which are overturned,” Singer said.

Hardman called the policy a “political move trying to play into the unpopularity of the refugee issues. If the decisions are being overturned on appeal, it doesn’t seem like a sensible decision and is a huge waste of Danish resources.”

Since most Syrians from Damascus and the Reef Dimashq regained their right to stay, Singer asked those from Tartus and Latakia to remain calm. “Syrians from Latakia and Tartus shouldn’t panic, I think they have a good chance of not having their residence permit withdrawn,” she said.

Singer attributed the high success rate of appeals to changes in the individual situation of refugees—for example, if they have openly criticized the Assad regime since coming to Denmark—as well as to the Refugee Appeals Board considering “their link to Denmark, in terms of private and family life, to be stronger than the immigration services did.”

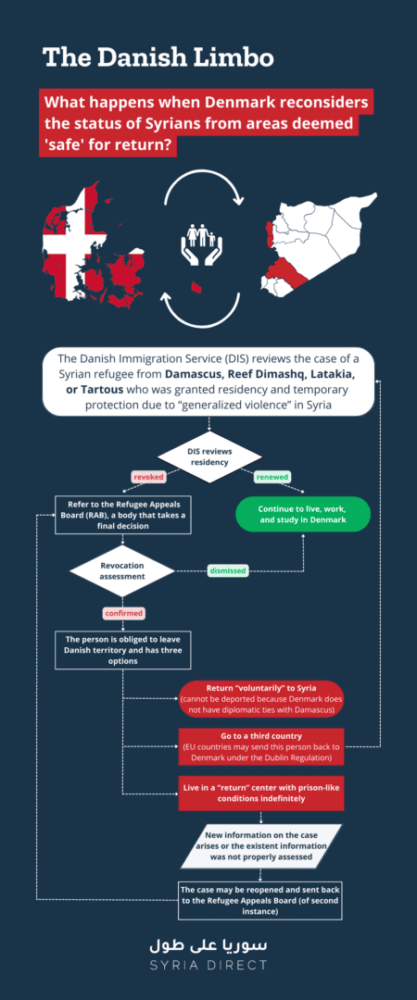

Infographic | The Danish Limbo: What happens when Denmark reconsiders the status of Syrians from areas deemed ‘safe’ for return? (Syria Direct)

‘An absurd notion of safety’

By considering parts of Syria safe for refugee returns, Danish policy contradicts European Union and United Nations security assessments.

“Danish authorities truly hold to this idea that safety is about bombs falling, the idea of generalized violence. These areas are under control of authorities that have continued to commit great violations of human rights,” Hardman said, calling the safety designations “absurd.”

Latakia and Tartus provinces are both controlled by Damascus. In 2022, 34 individuals in Latakia and 20 in Tartus were still “under arrest or detention or [were] forcibly disappeared in the detention centers of the Syrian regime forces,” Fadel Abdul Ghany, head of SNHR, said.

A 2021 report by HRW documented extrajudicial killings, enforced disappearances and cases of arrest and torture among Syrian refugees who returned to Syria. The same year, Amnesty International revealed cases of sexual violence against returnees by security officials.

“Our documentation from Syria shows that no returnee can feel safe from accusations of betrayal and punishment and is therefore at risk of violent abuse,” said Martin Lemberg-Pedersen, head of policy and documentation at Amnesty International Denmark.

In a 2021 report, Danish migration authorities reported two security incidents in Tartus and 119 in Latakia, and acknowledged that state authorities “continued to engage in arbitrary arrests, torture, forced disappearances and extrajudicial killings.”

The designation of Latakia and Tartus as safe is “just as problematic as the Damascus decision, and you could say even more so because we have more background information documenting the risk for returnees, which the authorities should take into consideration,” Singer said.

When al-Sheikh fled Syria in 2014, his son Ahmad was 12. Now 21, Ahmad is pursuing his studies in Denmark, the family’s home for the last nine years. “For me the most important thing is my son, his future is here, he’s studying baccalaureate, no way he will return to Syria,” he said.

But the designation of Latakia as safe has put the entire family’s future in jeopardy.

“In Denmark, this feels like a psychological war, like a slow death.”