Difficult diplomacy: Russia’s stranglehold on northwest Syria

Russia threatens to veto the delivery of cross-border aid to Syria at the Security Council. What is it seeking from this diplomatic ultimatum?

7 July 2021

AMMAN — Russia has vetoed no less than sixteen UN Security Council (UNSC) resolutions on Syria and has threatened to do so again at a key vote due tomorrow, July 8.

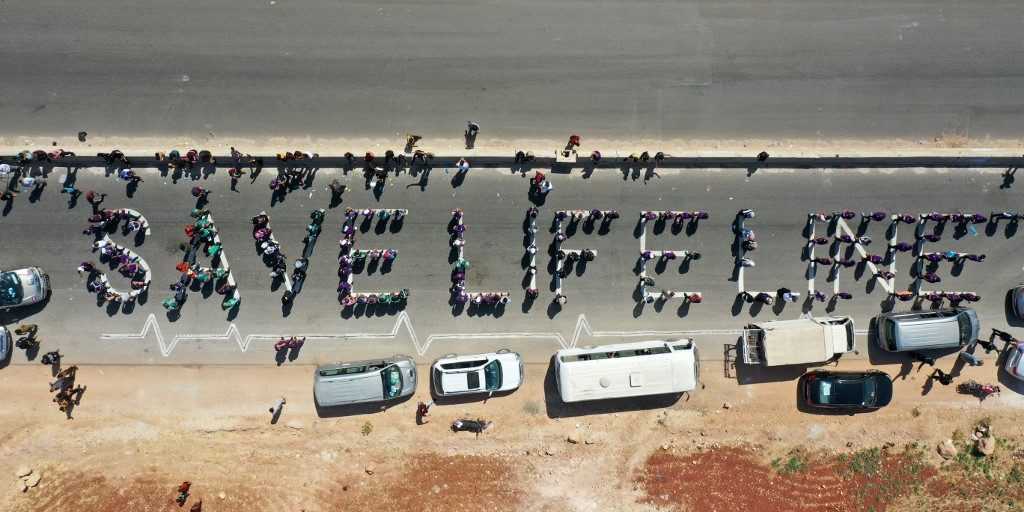

UNSC members have until July 10 to reach a consensus on a resolution renewing the UN’s authorization to deliver aid in opposition-held areas through the Bab al-Hawa border crossing with Turkey. Failing this, the UN’s ability to deliver aid into the region, where four million people live, will be interrupted.

On the eve of the vote, it remains unclear what Russia seeks to gain through this diplomatic showdown. Analysts and diplomats hope an agreement can be reached in the coming days – although the heart of the negotiations could be playing out outside the UNSC.

Renewing the lifeline

The cross-border aid mechanism was established in February 2014 through a landmark resolution authorizing the UN to deliver aid without Damascus’ approval through four designated crossings at Syria’s borders.

But in 2017, Russia, backed by China, started withdrawing support for the mechanism and abstained from an annual vote to renew the resolution. In late 2019, it openly broke away from the majority of the UNSC by vetoing the draft, insisting on excluding al-Yaroubiah crossing between Syria and Iraq. Last July, it used its veto power to further cut down the mechanism to a single crossing.

[irp posts=”42046″ name=”Lessons from al-Yaroubiah: Can cross-line aid replace the UN cross-border mechanism in northwest Syria?”]The initial draft of the upcoming resolution, penned by Norway and Ireland and shared with UNSC members on June 25, proposes the delivery of aid through the Bab al-Hawa crossing into northwest Syria (currently in use) and through the al-Yaroubiah crossing into northeast Syria (closed in January 2020).

Deeming the draft insufficient, the US also called for reopening a second crossing in northwest Syria – Bab al-Salaam, closed in July 2020.

The draft resolution will likely have evolved significantly by the time of the vote. Russia already discarded the possibility to reopen new crossings, calling it a “non-starter.”

What does Russia want?

Russia has stood firmly on the position that cross-border aid should be replaced by cross-line aid delivered through Damascus. Its proposed alternative to Bab al-Hawa is the opening of three crossings between regime and opposition-held areas.

Cross-line aid would position the regime centrally within aid flows and normalize its administrative power over aid, a preparatory step in Russia’s long-term agenda to attract reconstruction funding to government-held Syria.

“Cross-line assistance reinforces the power of the Assad regime,” Nicholas Heras, a Senior Analyst for the Washington-based Newlines Institute, told Syria Direct. “A significant amount of humanitarian assistance would be distributed by the UN via regime-held territory into the remaining areas of Syria that are not controlled by Damascus, expanding the regime’s [leverage] on the Syrian actors that oppose it.”

This would position the regime centrally within aid flows and normalize its administrative power over aid, a preparatory step in Russia’s long-term agenda to attract reconstruction funding to government-held Syria.

[irp posts=”26241″ name=”Russia urges Syrian refugees to return – with no guarantees for their safety”]The insistence on cross-line assistance is also driven by symbolic considerations. “Russia appears motivated to reaffirm Syria’s territorial integrity under the country’s sovereign government and to discourage any tendencies towards a more permanent division of the country,” Sam Heller, an analyst and fellow at the New York-based Century Foundation, told Syria Direct.

Uncertain concessions

Russia’s threat to veto the next cross-border aid resolution has fueled speculations about the concessions it is seeking from Western partners.

On June 16, the US and Russian presidents held a highly anticipated meeting in Geneva. However, no commitments were announced around the renewal of the cross-border aid resolution.

The alleviation of sanctions, which is in line with Russia’s goal to float up the regime’s economy, could also be among the bargaining chips of the Biden administration.

At the end of May, the Biden administration withdrew the license of Delta Crescent Energy, a little-known American company that was authorized to operate in northeast Syria’s oil fields by the Trump administration. The deal between the American company and the Kurdish-led coalition controlling northeast Syria was decried by the regime and by Russia, as Russian companies have competing licenses in the area. Therefore, some speculate the move was a gesture of appeasement – suggesting the US weighed “oil for an aid bargain with Russia” at the Security Council.

The alleviation of sanctions, which is in line with Russia’s goal to float up the regime’s economy, could also be among the bargaining chips of the Biden administration. In June, the US Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) issued a general license, valid for one year, authorizing all transactions and economic activities with Syria related to “the prevention, diagnosis, or treatment of COVID-19.” The license explicitly allows banks, NGOs and suppliers to deal with the Government of Syria and two sanctioned companies on these matters.

“I don’t think that this recent OFAC general license was linked directly to cross-border renewal, but it does fit into a larger effort by the Biden administration to signal its commitment to addressing Syria’s humanitarian need (…) and to dial down the Trump administration’s general bellicosity,” Heller noted. “This broader effort may contribute to a more functional dynamic with Moscow on Syria.”

In any case, Russia welcomed the move in a June 23 statement at the UNSC, saying it has “taken note of Washington’s attempt to loosen the sanctions pressure,” while calling on European states to consider similar measures.

A show of force

In parallel to these humanitarian discussions, Russia and the Syrian regime have engaged in a deadly show of force against Idlib, the heart of the last opposition-held enclave. In the past month, hundreds of strikes have killed and injured dozens of civilians, including first-aid responders, medical staff and children.

Strikes attributed to the Assad regime and Russian military in northwest Syria (June 1-25) – data provided by the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED)

“The Russians and the Assad regime escalate airstrikes on Idlib before the U.N. Security Council deliberations on cross-border aid into Syria as a means to signal to the international community that Assad, and not his foreign enemies, will determine the fate of his country,” Heras told Syria Direct previously.

At the same time, “the real goal of [the escalations] which take place from time to time is to send a message, or as the Syrian expression says, to “pull the ears” [of Turkish President Erdogan when he] seeks rapprochement with Washington and with Brussels,” Dr. Naser al-Yousef, a Syrian analyst specialized in Russian-Syrian affairs, told Syria Direct.

The Turkish player

The real solution to the cross-border showdown may well be playing out outside the UNSC: at the ongoing round of the Astana Talks (July 7-8) in Kazakhstan between Iran, Russia and Turkey.

Through the Astana process, Turkey and Russia have managed to mostly freeze the conflict in Idlib since March 2020. A land offensive on Idlib or the gradual collapse of its humanitarian ecosystem are likely to trigger new mass displacement towards Turkey, a nightmare scenario for the Turkish government.

But just as Ankara depends on Moscow for stability in Idlib, Russia seeks to preserve a functioning relation with Turkey to keep it from engaging the regime militarily. According to Heller, Turkish military influence on the ground and its working relationship with the militia controlling Idlib, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) will be instrumental in negotiating cross-line access.

Consequently, the Russians are likely to seek a pragmatic discussion with Turkey and settle on a solution that preserves the ceasefire. “There is a bit of a different atmosphere this year in the UNSC negotiations,” Kelly Petillo, Middle East and North Africa Programme Coordinator at the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR), told Syria Direct. “Turkey very much wants to keep the border crossing open, and it is very important for Russia to salvage this relationship.”