Killed, displaced, exiled: Syria’s women’s movement 13 years after revolution

As Syrians mark the 13th anniversary of the March 2011 uprising, activists reflect on the state of the women’s movement after more than a decade of revolution and war. In the face of conflict, displacement and persecution, what remains of it today?

15 March 2024

MARSEILLE/IDLIB — As Syrians mark the 13th anniversary of the March 2011 revolution this month, Ghalia al-Rahhal is far from home. The co-founder of Mazaya, an Idlib-based women’s empowerment organization, lives in exile in Berlin. She has been displaced twice: first by the Assad regime, then by an assassination attempt in northwestern Syria.

Al-Rahhal is originally from Kafr Nubl, a south Idlib town that rose to prominence as one of the creative hearts of the revolution. For years, demonstrators in the town regularly posed with banners written in English, addressing the Assad regime, world governments and global conscience.

A hairdresser before the revolution, when it began al-Rahhal became an activist, doing relief work and mobilizing in support of the uprising and Syria’s women.

When the regime recaptured Kafr Nubl in 2020, she fled north to territories beyond Damascus’ grasp, where the hardline Islamist organization Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) rules and Islamic State (IS) sleeper cells lurk, and where she continued working to empower women.

After around a year, “I faced a direct assassination attempt by car bombing,” al-Rahhal told Syria Direct. She suspects HTS or IS of being responsible. She fled again, this time to Turkey, and was finally resettled in Germany in 2023.

Al-Rahhal is far from the only Syrian women’s activist who has faced death and displacement in recent years. Muna al-Farij, an activist from Syria’s northeastern Raqqa city, was targeted by IS in 2014. Before the group proclaimed the city the capital of its caliphate, al-Farij was the only female member of the Free Raqqa Local Council—an opposition body founded shortly after the Syrian regime withdrew and the Free Syrian Army (FSA) took control of Raqqa in 2013.

“IS raided my family’s house to arrest me,” al-Farij recalled. She narrowly escaped by fleeing from the rooftop and made it to Turkey in 2014. “For four months I was afraid to even open the door of the house,” she said. In 2017, al-Farij returned to Raqqa after IS was expelled by the US-led coalition and Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF)—only to be forced to flee to Turkey again in 2019, she said, after facing stalking and extortion by a member of the SDF.

Women like al-Farij and al-Rahhal were an integral part of Syria’s revolution from the beginning, as organizers and active participants. As new spaces opened for political and social participation, feminist organizations took root and grew, and women made their voices heard in new ways. However, “we can’t mention the revolution without talking about 12 years of war that followed,” Maria al-Abdeh, who heads the rights organization Women Now for Development, said.

The reality in Syria today, after more than a decade of revolution and war, is bleak. Widespread poverty and insecurity hits women particularly hard, and women activists face wide-ranging threats: from de facto authorities, the Assad regime and their own communities. Some have been killed, displaced and driven into exile. Others still carry the fight forward on the ground, but the dangers they face are real. The recent hanging of prominent feminist activist Heba Haj Aref in northern Aleppo is one fresh wound that casts a long shadow.

Thirteen years after the 2011 revolution, what remains of Syria’s women’s movement?

Finding a place in the revolution

Al-Farij and al-Rahhal have vivid memories of peaceful demonstrations in their respective hometowns in 2011 and 2012. Women participated in sit-ins demanding the release of detainees from regime prisons and raised their voices to demand political reforms.

At that time, Maysa al-Mahmoud was a university student in Aleppo city. When the revolution began, she co-founded a local coordination committee there to organize protests in collaboration with similar groups in other Syrian cities. At first, she used a male pseudonym. “Not many women were joining protests because of customs and traditions,” she explained. With time, that changed, and al-Mahmoud started going by a female pseudonym.

As dissent spread, Damascus cracked down on its opponents, hunting, detaining and forcibly disappearing protesters. In 2012, al-Mahmoud’s home was raided, and she fled for opposition-controlled Azaz, in the northern Aleppo countryside. Relief groups, like one al-Farij created in Raqqa, worked to provide aid to those fleeing bloody repression.

Still, city by city, Damascus lost its grip and the FSA took control. As revolutionary ideas flourished, so did feminist ideas. Al-Abdeh, of Women Now for Development, remembers the 2011 revolution as “an important moment that struck the status quo, opening doors to ask questions and discuss topics that weren’t open to discussion” before.

Under single party rule in Syria, “we did not have this openness,” al-Rahhal said. Women’s political participation was largely restricted to the Women’s Union of the Baath Party. “Any woman who held a position spoke in the regime’s name,” al-Mahmoud added.

Today, “the circle of feminism is expanding, with more women joining,” al-Rahhal said. She sees this as a “success in itself, because we as Syrian women did not have knowledge of something called feminism.”

Bushra al-Dabel, who heads the Center for the Rehabilitation of Women and Children, a local volunteer organization in northern Idlib, agreed. “Before, women wouldn’t dare speak of their rights, nor did they know their rights,” she said. After the revolution, “they opened up and began to demand them.” These demands included “accessing job opportunities, having an opinion, and playing a decision-making role,” she added.

“There was a wonderful civil movement, with the formation of groups, civil society organizations,” including women’s groups, al-Farij recalled. Young men and women alike worked to organize elections in newly opposition-controlled areas.

As the years went by, some volunteer women’s groups, like al-Rahhal’s and al-Abdeh’s, later gained funding and became established non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Grants from international donors helped them expand and formalize their work, but also left them dependent on them. Today, as funding for Syria dwindles, this means their future is increasingly uncertain.

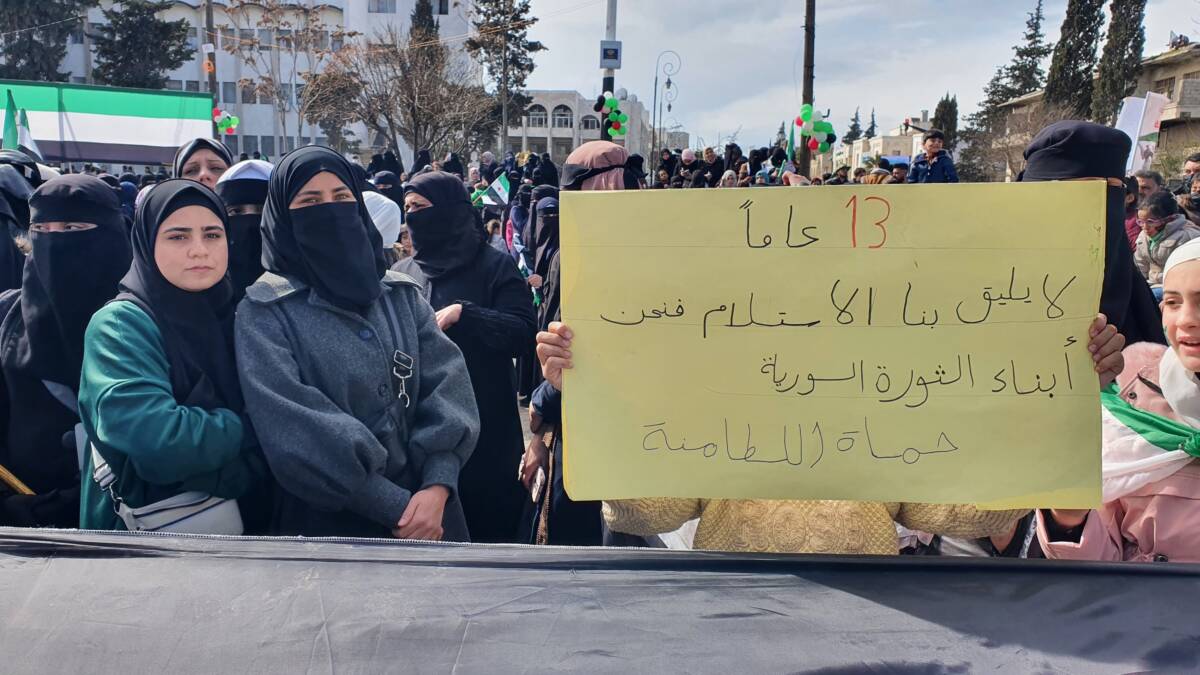

Women in opposition-held Idlib city, in northwestern Syria participate in a demonstration marking the 13th anniversary of the Syrian revolution, 15/3/2024 (Afaf Jakmour/Syria Direct)

NGOization

Founded in Kafr Nabl in 2013, al-Rahhal’s Mazaya organization started as a volunteer-run women’s center, providing professional training and first aid courses as regime barrel bombs rained down on opposition areas.

With external funding, the center expanded to become a well-established nonprofit. Today, it provides psychosocial support, education and literacy, and promotes political empowerment, such as voting, advocacy and leadership skills, for women in northwestern Syria.

Al-Abdeh’s organization, Women Now for Development, also started out as a volunteer-run initiative. Founded in 2012, the organization started out creating “safe spaces” for women in East Ghouta and Idlib, she said. Its activities today include psychosocial support, economic empowerment, and political engagement for the “future of a democratic Syria” across all areas of control.

But NGOization has come at a price: funding comes with “conditions” and follows “trends” depending on the catchword of the day, al-Abdeh said. It has also come at the expense of sustainability.

Both Mazaya and Women Now are currently at a crossroads as support for Syria is being scaled back. “The support must continue,” al-Rahhal said. “If the support is cut off, it will create a huge gap in society.” She fears an increase of “violence in society, including killings, assassinations and suicides.”

While al-Abdeh’s organization also relies on donor funds, she noted there are “organic initiatives that will continue even if they don’t receive funding.” For example, some groups like al-Dabel’s Center for the Rehabilitation of Women and Children have largely remained small volunteer organizations, only occasionally awarded one-off grants. Founded in 2017 in Kafar Takharim in Idlib Governorate, it is run by a team of 15 women volunteers.

The organization provides technical and professional training so that “women can become financially independent,” al-Dabel said, in a context where men are often absent—killed, disappeared or in exile. Her organization also provides legal services so that women can claim their housing and property rights, obtain inheritances and prove guardianship of their children.

Other grassroots initiatives include online women’s groups that mobilize around local and national issues. The Free Women of Syria Coordination Committee, founded by al-Mahmoud and other activists in 2014, is composed of women from across the country and abroad. The group’s members organize demonstrations on WhatsApp, most recently holding protests in Azaz to demand the release of detainees from regime prisons. They have also participated in demonstrations in solidarity with Suwayda’s protest movement.

These initiatives leave hope that Syria’s women’s movement is resilient. “Women will continue to fight, they don’t have a choice,” al-Abdeh said. Women, who reportedly now make up a majority of the population inside Syria, “will rebuild the country,” she added.

Women hold a 75-meter long flag of the Syrian revolution knit during a handicrafts workshop at the Mazaya’s women’s center in Kafr Nubl in 2014 (Mazaya Organization)

‘No horizon’

For all five activists, the conditions for women in Syria are inextricable from the country’s security, political and economic situation. This includes widespread violence, absence of the rule of law and insecurity that women are particularly vulnerable to.

“Syrian women did not get their rights, so they are still under threat,” al-Rahhal said. “The evidence is that a girl named Heba was killed,” she added, referring to activist Heba Haj Aref’s death on February 26.

Read more: ‘Today Heba, tomorrow us’: Feminist activist’s hanging casts long shadow

Haj Aref was found hanged at her home in northern Aleppo last month following a long string of threats, including from a powerful local faction. Local authorities ruled her killing a suicide shortly afterwards, without conducting an autopsy. However, fellow activists and members of her family have little doubt she was assassinated.

Members of al-Mahmoud’s group were deeply affected by Haj Aref’s death, but did not organize demonstrations due to widespread fear and concern for their safety, she said. “Other avenues are being used to pressure the local authorities to reopen the investigation,” she explained. The Syrian Women’s Political Movement, which al-Mahmoud is a member of, has called for an independent, international investigation.

Al-Abdeh described the security situation for women as “not any better in regime areas” and “a little better in northeastern Syria,” which is controlled by the SDF. For example, the SDF-backed Autonomous Administration in northeastern Syria has taken steps to penalize so-called “honor” killings beyond those taken by any other authority inside Syria. Still, these crimes continue due to deeply entrenched social norms.

Read more: Patriarchy stronger than law: ‘Honor’ killings persist in northeastern Syria

Meanwhile, the country remains suspended in a political stalemate. “There are no signs of a political transition, transitional justice or stability,” al-Farij. Where some semblance of democracy exists in areas outside of the regime’s control, women’s representation in politics remains symbolic at best, multiple activists said. “Women are only a front and a figurehead,” al-Farij said of northeastern Syria, where quotas exist for women’s political representation.

Syria is also facing its worst economic crisis since the 20th century. Poverty disproportionately affects women: women-led households are twice as likely to report being unable to meet basic needs compared to male-headed households. “Women took the largest share of the war, assuming the role of fathers as the wives or mothers of detainees or martyrs,” al-Mahmoud said, with hundreds of thousands of men killed or forcibly disappeared.

Feminist movements in stable countries have a “horizon,” al-Farij said. But in a context where “threats come from everywhere,” she fears what remains of Syria’s feminist movement has “no future.”

In Syria and across the region, the picture is “quite dark,” al-Abdeh said, referring to regional instability exacerbated by Israel’s ongoing war in Gaza. “We cannot begin to talk about a feminist future when children are dying of famine in the 21st century in Gaza,” al-Farij added.