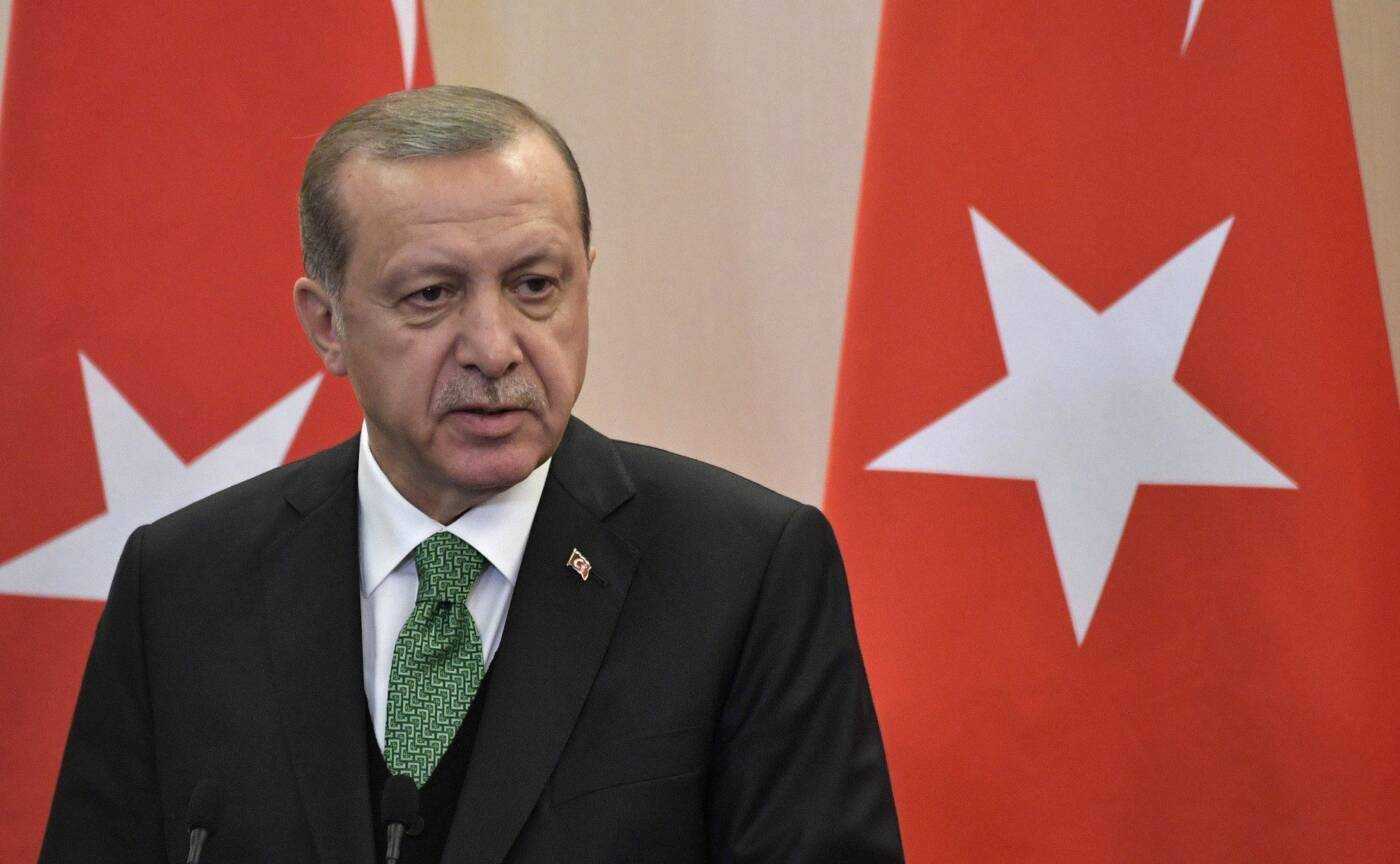

Erdoğan hints at normalization with Assad: Unpacking Turkey’s U-turn

With Turkey’s 2023 elections in sight and a surge in anti-refugee rhetoric shaping voter preferences, Erdoğan hints at possible reconciliation with Damascus. How could this apparent 180-degree policy shift play out in Syria?

26 August 2022

BEIRUT – Ankara is moving to mend ties with Damascus. At least, that is the scenario Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu hinted at earlier this month when he said it was necessary for the opposition and regime to “reconcile,” sparking a wave of protests in Turkish held areas in northwestern Syria. Erdogan later reaffirmed the need to keep “dialogue channels open with Damascus” and said the issue was “not about defeating or not defeating Assad.”

It remains to be seen how this apparent shift—from supporting the anti-Assad camp to opening up to reconciliation with Assad—could play out along the 911-kilometer, heavily militarized Turkish-Syrian border. After more than decade of conflict, this border has become a geopolitical nightmare of foreign powers holding conflicting agendas: United States (US) troops backing Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) next to Russian and Syrian army patrols in the northeast; former Al Qaeda affiliate, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) controlling Idlib; and the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army (SNA) and other proxy groups holding the northwest and a strip in the northeast.

In northwestern and northeastern Syria, the last two regions outside Damascus’ full control, the status quo appears unsustainable, yet frozen. Could a shift in Erdoğan’s position shake things up?

Is Erdoğan bluffing?

Analysts differ on whether rapprochement with Syrian President Bashar al-Assad is a real policy shift or just electoral rhetoric driven by a recent spike of anti-refugee rhetoric that has also seen violent incidents against Syrian refugees. Against the backdrop of Turkey’s economic crisis, 48 percent of Turkish citizens want the 3.7 million Syrian refugees in the country to return.

Turkish opposition parties have increased “pressure on Erdoğan to mend ties with the Assad regime because they see [it] as the only way to address Turkey’s refugee question,” explained Gönül Tol, Director of the Middle East Institute’s Center for Turkish Studies and author of the upcoming book Erdoğan’s War: A Strongman’s Struggle at Home and in Syria.

With re-election in 2023 in mind, Erdoğan is eager “to have some kind of deal that allows for the return of refugees, or that allows him to tell his voters that he has done something that would allow for the return of refugees,” said Nicholas Danforth, a Non–Resident Fellow at The Hellenic Foundation for European and Foreign Policy.

“It is hard to describe it as a policy shift, it is more statements for public consumption, to show the Turkish electorate that the AKP [Justice and Development Party] also has a plan on how to deal with refugees…and is ready to return Syrian refugees,” according to Elizabeth Tsurkov, a Non-Resident Fellow at the New Lines Institute for Strategy and Policy.

Erdoğan’s plan to deal with Syrian refugees has long included the goal of creating a “safe zone” inside Syria for them to return to. In May, he announced an eight-phase plan to facilitate the “voluntary” return of one million Syrian refugees to areas held by Turkish-backed factions in northern Syria. He also announced a cross-border military operation against the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) to create a 30km safe zone inside the Syrian border along the lines of the 2019 Operation Peace Spring. But that plan “didn’t play out the way he wanted,” Tol said.

Turkey’s threat to carry out a military operation in northeast Syria faced “significant pushback from the Iranians and the Russians,” forcing him to “backtrack” on this plan, Tsurkov said. The impossibility of creating a “safe zone” may explain this reconciliation rhetoric.

But for Armenak Tokmajyan, a researcher at the Carnegie Middle East Center, recent remarks by Çavuşoğlu and Erdoğan go beyond electoral rhetoric. “I don’t think it is just a bluff, in the sense that all these pre-election statements will be history once the election is over. Despite the animosity between Turkey and the Syrian regime in Damascus, both share the interest of killing the Kurdish political project in the northeast,” Tokmajyan said, adding that “sooner or later they need to talk and cooperate.”

Erdoğan has recently made several 180-degree policy shifts with countries he had rather troublesome relations with, such as the UAE, Egypt, Israel or Saudi Arabia. “We see a shift in Erdoğan’s foreign policy towards friendlier relations and increased cooperation with regional countries,” Tol said.

But the question is whether ties have only warmed in rhetoric alone. Danforth conceded Erdoğan had announced “rapprochements at large [with these countries], but has been hesitant to give the kind of concessions that would facilitate that rapprochement.” A key difference between reconciling with those countries and with Damascus is that the former “would help him manage the breakdown of ties with Washington,” but rapprochement with Assad “would play very differently in DC,” Danforth pointed out.

Domestic calculations dictate Erdoğan’s agenda in Syria

Each step Erdoğan takes in Syria has an explanation in domestic Turkish politics. “The main driver behind Erdoğan’s Syria policy has always been his efforts to consolidate power at home,” explained Tol.

As the 2011 Syria uprising led to war, Erdoğan joined a chorus of voices calling on Assad to step down and supported armed opposition groups like the Free Syrian Army, as well as Islamist factions such as Ahrar al-Sham and Faylaq al-Sham. Between 2011 and 2015, Erdoğan supported “the Islamist forces fighting against Assad in Syria,” Tol said. In her view, Erdoğan “had sidelined the secularists and embraced an Islamist narrative at home, so he could afford to pursue an Islamist foreign policy.” His main motive was “to consolidate power,” she said.

But in Turkey’s 2015 elections, Erdoğan’s party lost the parliamentary majority despite the backing of Islamist parties at home. “That’s when he switched tactics and aligned himself with Turkish nationalists,” Tol said.

This pivot shifted his priorities in Syria. “Toppling the Assad regime took a back seat to his efforts to curb the Kurdish gains in Syria,” Tol explained. “Every step that he’s taken in Syria has strengthened the Assad regime…Erdoğan has been weakening the Syrian opposition since 2015,” she said, citing Turkey’s withdrawal of support for rebels in Aleppo city in 2016.

“Turkey has succeeded in making the opposition not opposition anymore, but Turkish proxies,” said Suhail al-Ghazi, an independent Syrian researcher.

Erdoğan’s alliance with Turkish nationalists paid off. In 2018, Erdoğan led a transformation of Turkey from a parliamentary to a presidential system, with him at the top.

A year later, Turkish opposition parties calling for Syrian refugees to go back to their country swept the municipal elections. “In 2019, Erdoğan realized that the Syrian refugee ‘problem’ was going to be a bigger headache than he thought,” Tol said. “This new shift, which is talking about normalization with the Assad regime, is the culmination of that strategy.”

Tol expects Erdoğan to normalize ties with Damascus, though to what extent remains unclear. “Are we going to see a handshake between Assad and Erdoğan soon? I am not sure, but I think Turkey will take steps to increase cooperation and coordination with the regime,” she said.

But Danforth believes there is “a long way” to go before a handshake between Assad and Erdoğan. Public signs of rapprochement “would be of much more interest to the Syrian regime than to Erdoğan,” he said, because they would be seen as “much more of a concession of Erdoğan than from Assad.” Still, he agreed that reconciliation has been underway for some time. “Since 2014, Erodgan and those around him have given occasional hints that they’d be perfectly willing to reconcile with Assad under the right circumstances. The question has always been whether Assad would be open to the things that Erdoğan wants.”

Ankara’s agenda in Syria revolves around neutralizing the Kurdish project in north, ensuring the return of Syrian refugees and preventing any further exodus towards Turkey’s border. “If there were any kind of meetings between Turkish and Syrian government officials, Erdoğan would want to be able to announce correlated progress against the PKK or on the refugee issue,” Danforth said.

As for Kurdish forces in Syria and the areas controlled by the Autonomous Administration in North and East Syria (AANES), “for the regime to be able to fight the PKK it needs to have the desire and the the capacity to do so,” Tsurkov said. “Currently, the regime is way too weak to control these territories the SDF has controlled for many years,” she added. “Turkey has no reason to expect the regime to be able to prevent northeastern Syria from being kind of a PKK haven.”

Al-Ghazi agreed. “The regime cannot offer Turkey much,” he said. “They can offer information about YPG personnel for Turkey to track them and conduct an airstrike, but it can’t do anything more.”

Could the Syrian army absorb the YPG?

Damascus and Ankara’s interests converge in minimizing the power of Kurdish authorities in the northeast. One scenario to do so would be to integrate the YPG—which has sought support from Assad against the latest announced Turkish military operation—into the Syrian army, along the lines of the 5th Corps’ 8th Brigade in southern Syria. Following the 2018 southern settlements, former rebels were incorporated into the Syrian army under the 8th Brigade, with Moscow’s supervision. But analysts see this as a far-fetched scenario for northern Syria.

“In the abstract, both sides have an interest in minimizing YPG indepence, but the way that’s done is going to be difficult for them to agree on,” Danforth said. “Turkey’s preferred solution is not going to be Assad’s.”

Tsurkov said any YPG integration would be a “non-starter” for Ankara. “It will complicate the situation, because now [Turkey] can carry drone strikes against the PKK targets in NES; if those individuals become official parts of the military, it becomes harder to legitimize internationally that you are attacking the military of a sovereign state,” she said. Al-Ghazi and Danforth agreed that Turkey’s suspicions would not dissipate in such a scenario.

Unanswered questions leave the idea of YPG integration “vague,” Tokmajyanm said. “Would integration entail maintaining the command structure of SDF (which is dominated by PKK-related Kurds) or would it be abolished?”

Damascus may “accept low-rank officials, but the regime wants to be the only controlling force in every meter in Syria,” al-Ghazi said. Regime officials have said they would be willing to include them “as individuals but not as units, because they want to maintain control over them,” Tsurkov added.

Significantly, Ankara’s recent hints at normalization with Assad have been met by silence from the US, which has troops on the ground supporting the SDF in the fight against IS. Analysts agreed Syria is not a top priority for the Biden administration, which is waiting and watching to see where Erdoğan’s shift goes.

An unavoidable exodus in northwest

Northwestern Syria hosts 2.8 million internally displaced people, as well as a myriad of opposition, Islamists and Turkish proxy groups, all driven to a single corner of Syria after a decade of conflict. If rapprochement between Ankara and Damascus goes ahead, and Turkey withdraws, a regime takeover would lead to a mass exodus towards the Turkish border.

For significant rapprochement to occur, “the regime will not accept any type of Turkish presence in Syrian soil, and without Turkish military support, the rebels or the proxy groups that Turkey has maintained in northern Aleppo, they will be defeated by the regime, Russian and Iran,” Tsurkov said. “Syrian civilians and militants have no reason to trust the regime’s promises for civilian protection. They will try to flee, even at the risk of being gunned down at the border.”

An additional influx of refugees is a nightmare scenario for Turkey. And “the regime does not have the economic, political, security and military resources to retake and govern these areas with millions of people,” Tokmajyan said. So for now, “even if the regime advances on the Idlib front, there will at least remain a sliver of land between the regime forces and Turkey.”

Ankara’s “preferred solution,” as Danforth sees it, would be to reach “a deal with Assad enabling Turkey to leave without having to deal with a violent takeover.” But this option doesn’t fit into “Assad calculations,” he said.

Tol disagreed that Ankara would be willing to withdraw from the Syrian areas it occupies. “Some of the places are governed by Turkish municipalities, Turkey is sending Turkish imams, Turkish teachers, there is turkification going on—it is almost a nation-building exercise,” she said. “I don’t think that Turkey would withdraw…even if the Assad regime provides security guarantees.” The question is, as Assad continues to normalize ties with other countries in the region, “can Turkey remain in those regions when Russia and the regime asks Turkey to leave?”

Turkey may have painted itself into a corner in Syria. “Turkey has worked itself into a position that doesn’t have a great endgame,” Danforth said, referring to Turkey’s presence in the northwest. “HTS still has a lot of control in the northwest on its own and it’s not interested in making any kind of deal…the challenge for Ankara is to get its partners on the ground to go along with whatever it’s negotiated.”

“The lack of an endgame in the northwest will continue to be the major obstacle for the kind of rapprochement that Turkey wants,” he added.