Futile salary increase and fuel price hikes: Assad angers citizens and drags Syria towards a ‘true catastrophe’

Recent economic moves by Damascus impacted the cost of most basic goods and services, sparking a wave of protests in the country’s south and anger all the way to the coast.

23 August 2023

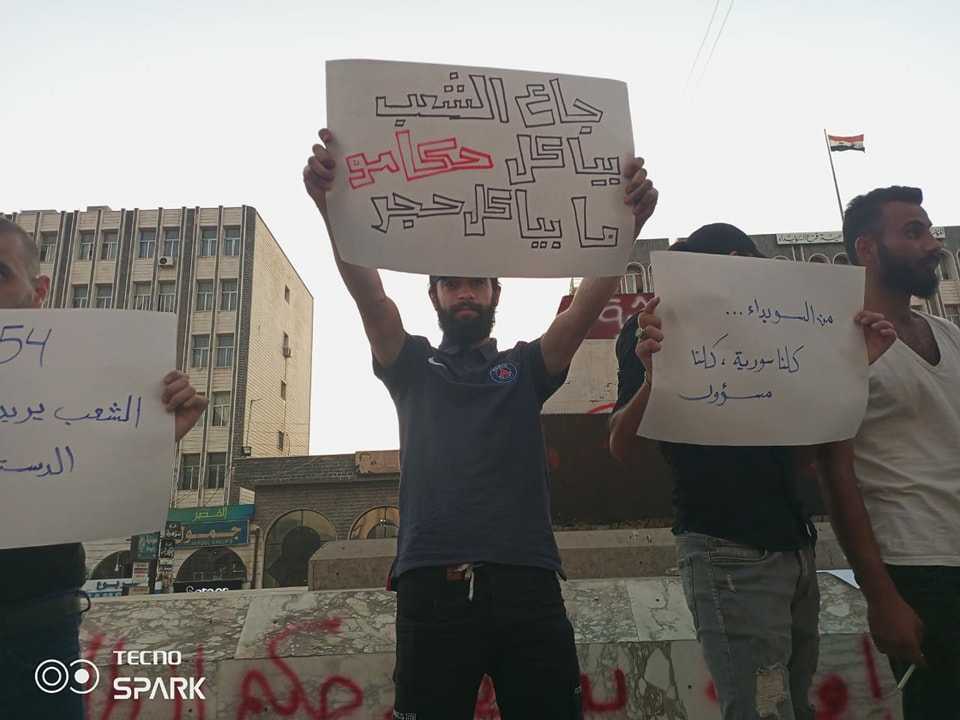

PARIS — Demonstrations continued in Syria’s southern Daraa and Suwayda provinces for the eighth day in a row on Thursday. For more than a week, protesters have decried deteriorating living conditions and called for the “fall of the regime” after Damascus hiked fuel prices on August 15 for the third time this year.

While the current protests are not the first Syria has seen in response to the country’s economic down-spiral, they appear to be more widespread than earlier outbursts: extending across Daraa’s Houran plain and Suwayda’s Jabal al-Druze. Discontent has reached the Syrian coast as well, where some activists have also voiced opposition to President Bashar al-Assad.

Syria’s official Syria Arab News Agency (SANA) has not directly reported on the ongoing protests in response to recent economic moves by Damascus.

On August 15, the same day the Ministry of Internal Trade and Consumer Protection issued several decisions raising fuel prices, Assad issued Legislative Decrees 11 and 12, doubling public sector salaries, wages and pensions. To some, it seemed as though the cost of increasing salaries was paid with one hand and recouped by raising fuel prices with the other.

The ministry set the price of one liter of subsidized mazot diesel fuel at 2,000 Syrian pounds ($0.13 according to the parallel market exchange rate of SYP 15,100 to the dollar at the time of reporting). The cost of industrial mazot was raised to SYP 8,000 ($0.52) per liter, and unsubsidized mazot to SYP 11,550 ($0.76).

Subsidized 90-octane gasoline was also raised to SYP 8,000 ($0.52) per liter, and premium 95-octane gasoline to SYP 13,500 ($0.89) per liter: an increase of 167 percent at fuel stations, sparking chaos in transportation services in the Syrian capital the day following the price hike.

To make matters worse, immediately following the two economic decisions, the Syrian pound fell against the dollar from SYP 13,900 to SYP 15,100.

The south ignites

As protests continued in Syria’s southern provinces this week, Druze-majority Suwayda recorded demonstrations at 40 different sites, extending into the center of the provincial capital on Tuesday. The province also saw an unprecedented general strike on Sunday and Monday, with protesters forcing government offices to shut down, blocking roads and renewing chants for “Assad’s departure” previously heard in 2020. That year saw a previous round of protests in Suwayda in response to the country’s economic crisis.

Neighboring Daraa province, which has seen occasional demonstrations since the signing of a Russian-backed settlement agreement between opposition factions and the regime in the summer of 2018, did not miss the opportunity to renew protests.

Demonstrations have broken out in the majority of Daraa’s cities and towns, accompanied by anti-regime graffiti. Protesters focused on deteriorating living conditions, calling for the regime to fall and for the release of detainees from its prisons. Some Daraa cities have been under an open-ended general strike since Sunday, August 20.

Economic floundering

Damascus’ latest economic decisions have impacted the prices of most basic goods and services, including the black market price of fuel. Following the fuel hike, the cost of one liter of black market gasoline rose from SYP 10,000 to SYP 18,000 (from $0.66 to $1.19), while one liter of mazot rose from SYP 8,000 to SYP 15,000 ($0.53 to $0.99).

The cost of food also increased as the exchange rate of the pound fell. In the northern Daraa city of Inkhil, the price of a kilogram of sugar rose from SYP 11,000 to SYP 14,000 ($0.72 to $0.92), a liter of vegetable oil from SYP 23,000 to SYP 30,000 ($1.52 to $1.98) and a 16-liter tank of olive oil from SYP 800,000 to SYP 1.2 million ($52.90 to $79.40), Abdulmajid al-Ahmad (a pseudonym), 27, who lives in the city, told Syria Direct.

With prices on the rise, it is as though the salary increase never happened. “It is not a solution,” al-Ahmad said. His father’s monthly pension as a retired teacher rose to SYP 220,000 ($14.50) from SYP 110,000 ($7.25) after the August 15 increase. But “it is only enough for three days,” he said. “The cost of filling a 30-barrel tank of drinking water is up to SYP 100,000 [$6.60],” nearly half the monthly pension.

This month’s economic moves by Damascus indicate “a major state of confusion in the regime’s economic policies,” Karam Shaar, the director of the Syria Program at the Observatory for Economic and Political Networks, told Syria Direct. “The regime was counting on economic support from Arab Gulf countries, but it seems it did not come.”

“The regime is aware that lifting subsidies in the manner and at the level that happened means the salary increase will last one or two months, and that it will evaporate due to the lifting of fuel subsidies, which impacts other goods,” Shaar added. The food industry and others “rely on fuel, directly or indirectly.”

Raising salaries the same day as fuel prices likely aimed to “lessen the degree of anger in the street, but it didn’t work because many people and experts agree that the doubled salary has no real meaning,” he said.

Manaf Quman, an economics researcher at the Turkey-based Omran Center for Studies, said “the salary is supposed to be measured by the rate of the increase in the prices of goods and services.” For example, the average monthly cost of living for a Syrian family of five is around SYP 6.5 million ($430) per month, while the minimum needed is SYP 4 million ($264). Some families estimate they need between SYP 150,000 and SYP 250,000 ($9.90 and $16.50) per day to spend on food for a family of four. In other words, “the salary an employee takes home at the end of the month is spent in the market in a single day,” Quman said.

“Whoever wants to raise salaries and wages has to ensure stability in the production rates of basic goods, and the increase in the money supply should be an expression of growth in real production to ensure price stability,” he told Syria Direct. “None of this has happened in Syria over the past years. The regime prints banknotes without the slightest value. This increase will evaporate before it reaches the hands of an employee, due to the market’s reaction and the imbalances in the economy.”

Damascus’ “intertwined” economic decisions to raise salaries and hike fuel prices can be explained through two main dynamics, according to Joseph Daher, a political economy researcher at Lausanne University in Switzerland. The first is the lack of state funds, as “the regime’s resources, reserves and revenue significantly declined during the war. In response, the government adopted austerity measures and cut subsidies on basic goods—such as bread and oil derivatives—leading to worse living conditions for large segments of the population,” he explained.

These policies, in Daher’s view, have “widened social, economic and regional inequalities—repeating the problems that existed before the war broke out in 2011.”

The second dynamic he described is that “the regime’s current policies are a continuation of austerity policies, accompanied by further liberalization of the economy, which the regime began before 2011 and accelerated in the past few years.”

Like other countries in the Middle East and across the world, “the Syrian regime often seizes crises as opportunities for economic restructuring, to push change forward in ways that were previously forbidden—including reducing the social role of the state, stopping subsidies and further liberalizing the economy,” Daher said.

More inflation

Syria has the third-highest level of annual economic inflation in the world, at a rate of 238 percent, after Venezuela and Zimbabwe, according to economist Steve Hanke’s Annual Misery Index. The index measures global economic inflation rates according to the data of local currency exchanges in the parallel market.

Locally, Rasha Sirop—an economist close to the regime—estimated in a Facebook post in June that inflation rates in Syria reached 16,137.32 percent from 2011 to 2023. In other words, prices increased by more than 161 times over 12 years.

These levels of inflation, as well as the national currency’s loss of value, have impacted the population’s purchasing power and significantly increased the cost of living.

The first half of 2023 saw the average national price of a standard reference food basket increase by 27 percent, reaching around SYP 530,000, or around $81, according to the official exchange rate at the time of SYP 6,540 to the dollar, political economy researcher Daher said. However, this past June, the cost of the basket became 70 percent more expensive than it was 12 months ago—around seven times costlier than it was in 2020.

Runaway inflation has tangible social consequences. “Increases in the cost of oil derivatives not only affect the structure of economic production, but also the entire society,” Daher said. He pointed to the negative impact of rising transportation costs on people who live outside main urban centers, where most state institutions and major economic activities are located. Similarly, increasing numbers of university and high school students who live in remote areas have stopped traveling to their places of study due to high transportation costs.

Higher transportation costs have also led to “more absenteeism in public institutions,” as “transportation costs sometimes account for around half an employee’s salary,” Daher said. An increasing number of employees in Syria’s public sector are resigning from their positions due to increased transportation costs and low salaries. In response, the regime has taken a number of measures to tighten the conditions for a resignation to be accepted.

In June, the Ministry of Education issued a memo specifying the conditions for accepting the resignation of its employees. These included that workers must have served for 30 years or more, been granted unpaid leave for two consecutive years, or have a specific health condition that prevents them from performing their duties.

Higher oil prices also have knock-on effects in housing and daily life: “The costs of running private generators are extremely high, leading to longer power outages,” Daher said. This has changed consumer behavior. “Electricity, whether provided by the public sector or private generators, is not able to operate refrigerators,” so “families generally buy food for one day only, or buy products that have a shelf life of a few days without the need for refrigeration,” Daher said.

Returning to Iran’s embrace?

Several Arab countries are trying to achieve tangible progress in the Syrian file, through a series of normalization efforts and a Jordanian-led Arab initiative. But there are little signs of progress, whether in terms of the level of discussions with the Assad regime or the flow of Arab assistance to cash-strapped Syria.

On August 15, the Arab Ministerial Contact Committee on Syria convened a meeting in Cairo of the foreign ministers of Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Jordan and Lebanon, as well as the Syrian regime. The meeting’s concluding statement held nothing new.

Progress is slow, with Arab states dissatisfied as a result of the continued flow of drugs from Syria and the regime’s failure to take concrete steps within the framework of the “step-for-step” Jordanian initiative, which includes “trust-building steps” in the first of three stages. Meanwhile, the regime’s economic collapse continues, leaving it with the choice of either creeping towards the embrace of Arab states or turning back to Iran.

In May, Reuters reported that Saudi Arabia offered Assad $4 billion in exchange for stopping the captagon drug trade, citing sources close to Damascus and the Gulf. A Saudi Foreign Ministry source denied the report.

“The regime was promised Arab money,” Shaar said. “In their context, these figures are bigger than Syria’s budget over the past two years, which ranged from $2 billion to $3 billion. But the money didn’t come as a result of pressure from the West, which insists on the regime making real concessions in exchange for funds.”

Losing hope in obtaining Arab funds leaves Damascus with “no real supporter left but Iran, if Russia is excluded as its military and political intervention is greater than its economic [intervention],” Shaar added. This has prompted Damascus to “make investment concessions in Syria to Tehran at an unprecedented pace.”

In the face of this complex situation, “there is no horizon for the Syrian economy,” researcher Quman said. “There are no partial or sustainable solutions, so long as the economic policies remain the same, and the regime’s approach continues as though we were in 2011.”

He expected “further price increases and a continued collapse of the pound, strengthening the course of Syria’s economic crisis.” Worsening economic crisis “increases the poverty of citizens, driving them to think of emigration,” with “children dropping out of school and turning more towards illegal activities—such as working in drugs and the like.”

All signs indicate that “Syria’s near economic future is very bitter,” Shaar concluded. “There seems to be no way out of the current situation, except through a political settlement that returns private capital, loans and foreign investment to Syria. If not, things are headed for a true catastrophe.”

**

This report was originally published in Arabic and translated into English by Mateo Nelson.