Keeping hope, but still waiting: Syrian feminism and a decade of revolution

Women’s presence and role over the past decade reflect the course of the revolution: the militarization, emergence of separated areas controlled by different international, regional and local actors, as well as the rise of extremist groups such as ISIS and HTS.

4 March 2021

AMMAN — Razan Zaitouneh, Samirah al-Khalil, May Skaf, Fadwa Suleiman. These are the names of women who have become, with many other Syrian women, defining figures and symbols of the Syrian revolution.

The Syrian revolution was sparked in 2011 by the Assad regime’s brutal response to peaceful demonstrations. Women’s contributions to the revolution over the last decade – as activists, journalists, teachers, doctors, field nurses and even fighters – “did not come from nothing,” according to Yasmin Sharbaji, a human rights activist and coordinator of the Families for Freedom movement in Lebanon. Rather, it came after years of the Assad regime imposing “political tyranny” and “detaining educated women.”

Prior to the revolution, there was the “social tyranny [embodied by] customs and traditions that frame women’s work as caring for her husband and her children,” Sharbaji added, and “religious tyranny, which is the false understanding of religion as man’s guardianship over woman, even if he is beating her; and economic tyranny, represented by [denying her the right] to work outside the home and obtain an independent income.”

“Many women paid with their lives for their belief in the revolution. Others were detained, and their rights were violated after they broke taboos in the society, crossing red lines with their bravery and enthusiasm for change,” Alia Ahmad, a researcher and trainer on women’s rights who currently lives in Germany, said. That led to “the formation of a kind of parallel society, which may be small but posed a challenge to the patriarchal society that gripped many aspects of women’s lives.”

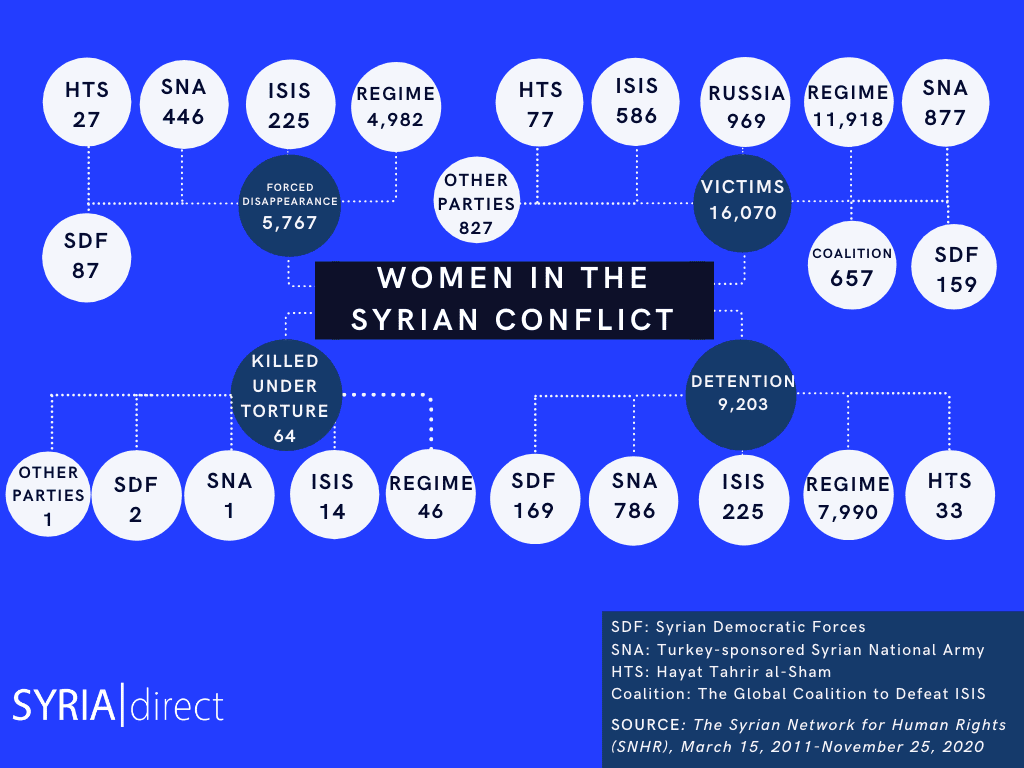

However, women’s presence and role over the past decade also reflect the course of the revolution: the militarization, emergence of separated areas controlled by different international, regional and local actors, as well as the rise of extremist groups such as ISIS and Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS). All this has cast a heavy shadow on the Syrian feminist movement, which has become subject to the de facto authorities controlling the different areas of influence.

Fragmentation and a crisis of priorities

The Syrian feminist movement in territories outside of Damascus’s control “has so far been unable to crystallize its identity and vision to deal with different issues from a feminist perspective,” Alia Ahmad said. Further, “it suffers from fragmentation, in addition to the contradictions and gap between slogans and theoretical proposals on the one hand, and practice on the other.”

“We’ve come to see closed-off feminist collectives, real-life and virtual, that put forth glittering slogans but which, in their behaviors and interactions, blend into the exclusionary patriarchal mindsets that reject difference,” Alia Ahmad added. “This sometimes drives women who have approached these feminist bodies or who have dealt with their representatives, to reject feminist thought and its propositions, and view it as a claim with no basis: just a job, a way to make a living.”

Similarly, while Sharbaji considers the emergence of feminist organizations “promising,” they “lack coordination” in general. “We often see several feminist organizations in the same area proposing the same projects to empower women,” she said, “rather than agreeing amongst themselves to implement various projects that would lead to the empowerment of women in different fields.”

There is also the “funding agendas” problem, according to Ilham Muhammad (a pseudonym), an activist in Idlib who asked for her identity not to be revealed. Donors “do not understand what women need and the marginalization they have been suffering for decades,” she explained. “Many women’s basic living needs are not ensured, so how can we empower them with their rights while not securing the least of their rights – the right to live?”

The funding problem is not limited to inside Syria and extends to countries of asylum such as Lebanon. There, “the funding bodies often impose workshops discussing the consequences of child marriage,” Sharbaji said, “and in this case, a Syrian woman says: How can I not marry off my daughter when I cannot support her?”

“We are still suffering from men’s view of women’s work as silly. I have met women who have lost their breadwinners who work outside and inside the home with an energy that no man could bear. Unfortunately, loathsome customs still govern us.”

Different environments, different rights

As if historical obstacles were not enough, the extremist organizations’ control of women in some regions, the latest of which is Idlib, has led “to a rollback of women’s gains” in those areas, Sharbaji said. Ilham Muhammad echoed the sentiment. Despite the “active role” of feminist thought and its institutions after the revolution “to recruit and empower women,” Muhammad said, it is still “a modest empowerment due to several reasons, including HTS [Hayat Tahrir al-Sham] control over [northwest Syria].” Besides, there are the issues of “the funding, mentality and patriarchal [practices] that still prevail in our society.”

Throughout the Syrian revolution, many feminist organizations emerged to empower women in northwest Syria. These include the organization A Glimpse of Hope, active in the city of Idlib since 2015, the Syrian Women’s Collective in the Idlib countryside cities of al-Bab and Azaz since 2017, the North Syrian Women’s Association in Jabal a-Zawiya since 2017, the Women Now center in Maarat a-Numan that opened in 2014, and the Sama volunteer team.

The areas of northeastern Syria controlled by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) supposedly present a different model to that in the northwest, especially the HTS-controlled areas. Women in the Kurdish-majority region enjoy a relatively broad scope of participation in the institutions of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES). Since its foundation in November 2013, the AANES implemented a co-presidency system, whereby women occupy at least 50 percent of all official and community councils and institutions. These institutions also include women’s councils, committees and legislation aimed at protecting women.

However, this is not necessarily reflected in other spheres of life. The “law is still not sufficient, both in terms of its content and its implementation,” Ghandi Safar, the director of the Eridu Center for Civil Society and Democracy in northeastern Syria’s Qamishli city, previously told Syria Direct. “Many women are afraid of resorting to the courts.”

Conversely, the Syrian woman has been able “to develop better and realize higher achievements” in European countries, according to Sharbaji, because she “shook off the dust of the patriarchy that adopts the principle that [men] are entitled to what women are not. She has been able to learn her rights and duties and assert herself. She became an active member of her environment, managing her duties as a mother and a father at the same time.”

The feminist organizations active in countries of asylum include Together to Make Decision, which started working in Turkey in 2016; the Syrian Women’s Political Movement, founded in Paris in 2017; the Syrian Women’s Movement, established in Sweden in 2013; and the Syrian Women’s League – Turkey, founded in 2015.

Feminist political work

In late 2019, eleven months after she was appointed to the Idlib Local Council of the HTS’s Salvation Government, Amina al-Ahmad resigned from her position at the council’s Women’s Office.

“Women’s representation is declining within the HTS-controlled local councils,” al-Ahmad told Syria Direct, “because of the authoritarian [behavior] of the men in them over the women, even in expressing opinions.” That, in turn, goes back to “the military policies and traditional mentality against women taking on any political or administrative position.”

Muna Muhammad, a former member of the AANES’s Raqqa City Local Council, was forced to “leave work and sit at home,” she said, because of her tribe. While the AANES granted women in northeastern Syria “rights we did not dream of in the time of Daesh [ISIS],” she said, tribalism “restricts women’s work as a whole, not only in politics.”

As for women’s political presence in the institutions that are supposed to represent the revolution, it still “follows a limited approach, under the pretext of a lack of capacities,” Sharbaji said. “Despite the presence of many female politicians who can take up the helm of leadership,” she said, men “do not want them to enter the political arena so as not to fight for women’s rights.”

This reality extends to political parties as well, according to Amina al-Ahmad. “Women’s representation in the political parties and bodies formed after the revolution is insufficient.” The reasons for that are “the domination of patriarchal thought and the trivialization of women’s capabilities in positions that do not fit the stereotype,” she asserted. “It is also unpleasant to many to have women as peers in decision-making positions.”

What does the future hold?

In addition to women’s representation in the AANES’s institutions and legislative changes related to women in northeast Syria, many of the feminist institutions established in northwest Syria have also “played a role in preparing some women to enter the labor market, especially since many of them have lost their breadwinners,” according to Muhammad. These institutions, she believes, have made “a great achievement within the available capacities. By realizing material self-sufficiency for women, their perception expands to think of themselves and empower themselves in other scientific and cultural fields such as learning languages and using computers, and then training others.”

Still, the number of beneficiaries from empowerment programs “is negligible compared to the huge number of women who need work, while we still suffer from men’s view of women’s work as silly. I have met women who have lost their breadwinners who work outside and inside the home with an energy that no man could bear. Unfortunately, loathsome customs still govern us.”

The feminist movement has “a beautiful face,” but “its activation remains unclear,” according to Sharbaji. While pointing out that there are men who came out during the revolution to support women’s rights, “they are still few,” and “many still believe that a woman’s voice is nakedness [‘awrah] and that she should be confined—not out of fear for her, but fear of her.”

On the other hand, “feminist representatives, activists and organizations,” in Alia Ahmad’s view, “have not yet succeeded in reaching out to the targeted group on the ground. Feminist discussions are generally limited to media platforms and are far from the interests and perspectives of most of the community and have no notable popularity.”

Nonetheless, “the Syrian feminist movement is taking its first shuffling steps,” she said, “and it is unfair to start evaluating its achievements from now. The obstacles are many.”

“Women are now learning to organize themselves, shuffle their cards and work together in challenging and complex circumstances. They seek to develop a general feminist vision that includes multiple and fragmented feminist identities.”

This report was originally published in Arabic and translated into English by Mateo Nelson.