Incomplete awareness: Syria’s primary school curricula lack information on future water crisis

Facing the impacts of climate change and the fallout of a war that turned water into a weapon, what are Syria’s children learning about the dangers of the water crisis they face?

20 December 2023

By 2050, the year in which the annual water deficit in Syria is projected to reach more than 6 billion cubic meters, students currently in the first grade will be 33 years old. What are they learning today about the dry future they face?

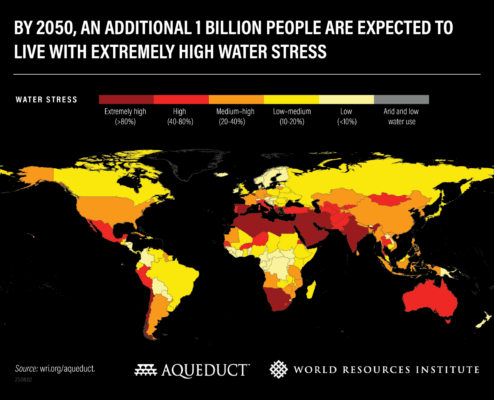

A map showing parts of the world facing the greatest threat of water insecurity by the year 2050 (World Resources Institute)

Syria and other Arab countries are among those most vulnerable to water insecurity. According to research citing the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations (UN), Syria has been classified as among the most water-poor countries since 2000.

One report, published by the international humanitarian organization of Action Against Hunger in 2020, warned of increasing water insecurity in Syria, noting that 15.5 million Syrians were in need of safe water. This held true across the country’s different areas of military control: territories held by the Syrian government, opposition and the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES).

Water and climate experts have warned that Syria is threatened by inevitable drought by 2050 if authorities do not take strict measures to prevent it.

“Before the Syrian crisis broke out, there were many challenges in managing the quantities [of water] available in the country with the average consumption in the agriculture, industry and daily use sectors,” said Adib al-Usta, a climate and water researcher living in Damascus. Then, “the war heavily damaged water infrastructure and reduced access to clean and safe water.”

“Providing clean and safe water to the population in Syria is a major challenge that entails improving the water infrastructure and implementing the necessary projects to meet basic water needs,” al-Usta added.

Taysir Muhammad, a water expert living in Syria’s northwestern Idlib province, agreed with al-Usta, adding, “changes to the climate threaten a harsh water future for Syria.”

The World Bank reported in April 2023 that, by the end of the current decade, the annual amount of available water per capita in the Middle East and North Africa would fall below the absolute limit of water scarcity, which is 500 cubic meters per capita annually. The report estimated that, by 2060, an additional 25 billion cubic meters of water will be needed every year to meet the region’s water needs.

These natural factors, along with more than a decade of war that saw water used as a weapon and the control of the flow of water by countries upstream—as in the case of the Euphrates River, which originates in Turkey and flows through Syria—raise an important question. Do the children of Syria, who will be young adults when the coming water crisis reaches its peak, have sufficient awareness of the dangers they face? Do current school curricula across the country’s different areas of military control provide the information they need about all aspects of this issue, from health to agriculture and the economy?

The results of 72 questionnaires distributed by the reporters to students and teachers across three areas of control in Syria show varying answers to questions about education on water and the future crises the country faces. Sixty questionnaires were given to primary school students, 20 for each area of control, and conducted in the presence of at least one parent outside of school hours. Twelve teachers were also surveyed, while direct interviews were conducted with educational officials involved in curricula across the three regions.

A written consent form obtained by the reporters before interviewing children, 2023 (Semav Hesen/Dahab Noura)

Cholera outbreak

On December 11, 2023, the number of suspected cholera cases in northwestern Syria—an opposition-controlled area inhabited by more than four million people— among them nearly two million displaced people, reached 186,297, according to the figures of the Early Warning Alert and Response Network (EWARN) of the Assistance Coordination Unit (ACU).

Several Syrian provinces have recorded an outbreak of cholera since late August 2022, in a country suffering from a shortage of potable water and pollution due to poor sewage systems. Displacement camps, in particular, lack minimum conditions for sterilization and hygiene.

Globally, “changing weather patterns, driven by human activity and burning of fossil fuels, is contributing [sic] to record numbers of cholera outbreaks,” World Health Organization Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said in a media briefing on November 29.

Weekly Report of the Early Warning Alert and Response Network, 11/12/2023 (EWARN)

Omar Hassoun (a pseudonym), 11, was infected with cholera along with all his family members on August 20, 2023. The family, which lives in the Idlib countryside city of Harem, does not know what caused the infection. “It could be the mixing of groundwater with sewage, or vegetables being watered with contaminated water, which is one of the causes,” Omar’s father told a reporter.

In a country with a collapsing health sector that is being struck by a cholera outbreak, “the primary school curriculum doesn’t address the effects of pollution on health, nor types of diseases and ways to prevent them,” Omar said. The sixth grader said he first heard about the cholera epidemic from Syrian Civil Defense teams conducting cholera awareness campaigns, he explained by phone.

Omar received only “very basic information about the epidemic and ways to prevent it from the school, despite the infection of a number of classmates,” he added.

The military actors in control of different parts of Syria may vary, but the situation of children is largely the same across geographical areas, especially regarding health awareness and education.

Ward Ahmed (a pseudonym), 12, lives with his family in Syrian regime-controlled areas of Aleppo city. He was also infected with cholera, and due to the high number of infections in Aleppo, “the analysis sample was sent to Damascus,” his mother said. She does not know how her son was infected, but “heard the water in Aleppo is contaminated.”

Ward “did not know about the dangers of water pollution and that it may cause death,” he said. Like Omar, he did not receive sufficient information about the epidemic, except for “instructions regarding washing hands and sterilizing fruit and vegetables.”

Manifestations of the water crisis, driven by nature and the conflict, have reached life-threatening levels in northeastern Syria as well. In 2022, more than 15,483 people there were infected with cholera, 28 of whom died.

On May 24, 2023, the number of infections in northeastern Syria reached 35,745 cases, according to the latest statistics issued by the EWARN. Justice for Life, an independent non-governmental human rights organization, warned that the health situation indicates that a cholera outbreak is likely to happen again “if the factors of its outbreak are not addressed on the local and international levels.”

In Syrian-government-controlled areas, the last update on the number of infections by the Ministry of Health was in January 2023, when the Ministry announced 1,652 confirmed cases of cholera and the deaths of 49 people.

Shallow information

The Global Drought Observatory (GDO) issued a drought alert for the eastern part of Syria in April 2021, noting that the percentage of cultivated land had declined by 53 percent, affecting livestock and agriculture as well as human and economic capital.

Today’s children are the ones who will face the consequences of drought when the water crisis is at its future peak. Hence, it is important to understand the current role played by Syrian educational curricula, across different areas of control, in raising awareness. How have curricula addressed Syria’s water crisis? Do students have enough information about the future risks of drought they face?

Reporters analyzed elementary school curricula—covering grades one to six, or ages six through 12—in Syrian government territory, the opposition Syrian Interim Government (SIG)-held northwest and the AANES-held northeast.

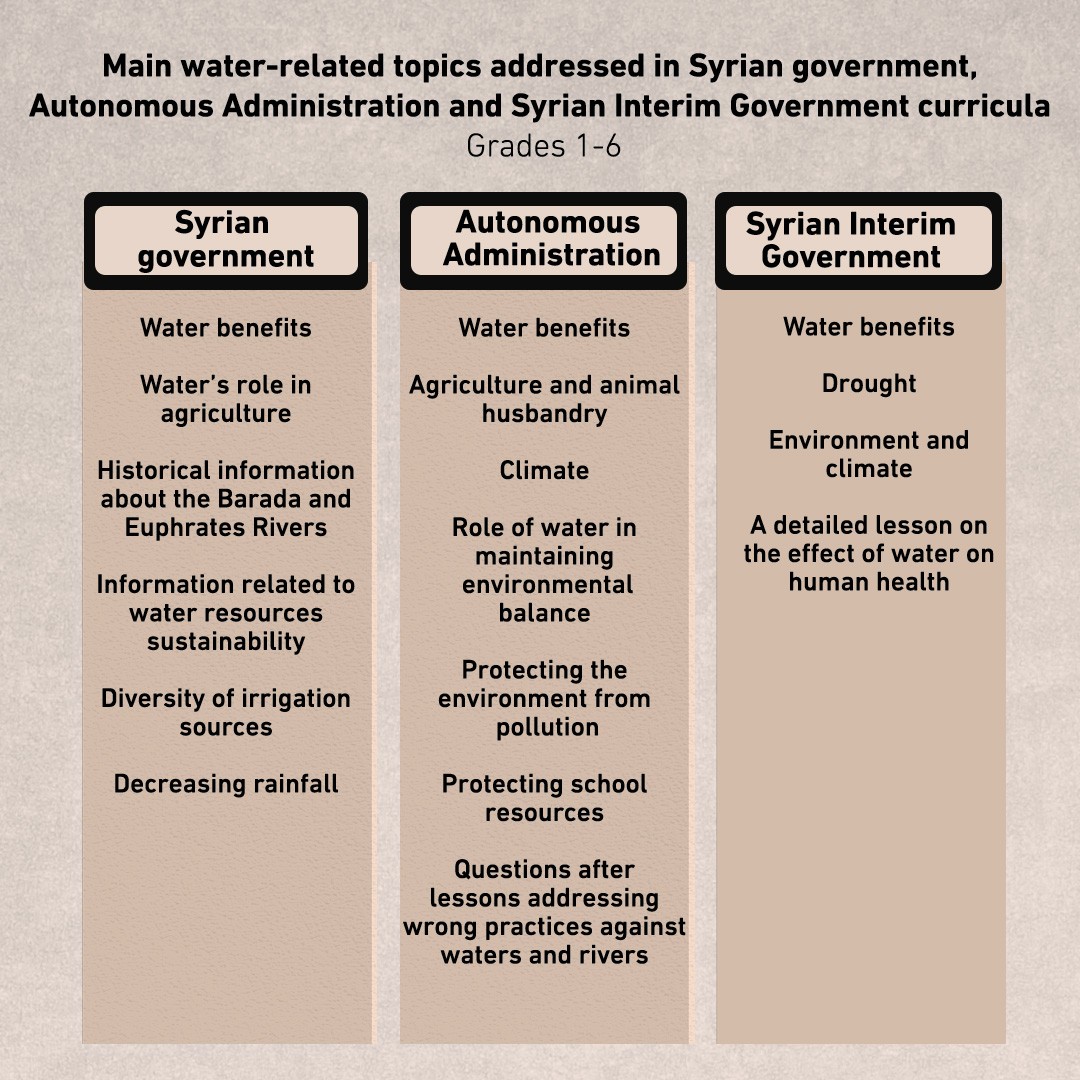

In government areas, subjects dealing with water issues include: biology, Arabic, social studies and emotional education. These courses touch on many topics, including agriculture. In SIG areas, biology, reading, social studies and Arabic classes include lessons on water. The government curriculum included 26 lessons related to water, compared to 14 in SIG areas and AANES areas, respectively.

Water-related topics covered in the Syrian curricula from first to sixth grade in the areas controlled by the Syrian government, AANES and SIG, 2023 (Simav Hesen/ Dahab Noura)

All three focused on knowledge of the historical reality of water in Syria, as well as drought and water resources, but neglected the impacts of drought on life and the economy. They also neglected the danger of climate change and its repercussions on water security in the years to come, although the curricula were updated or published coinciding with the environmental changes taking place in Syria.

Incomplete awareness

One Arab study, prepared to celebrate the World Water Day on March 22, 2002, pointed to the need to intensify campaigns aimed at mobilizing collective awareness, the impacted public and others to deal with the regional water situation. According to the study, curricula should discuss pressing issues, including: the proper use of water, information about local water issues, water security and sustainable management and water-related health education.

Syrian primary schools across the three areas of influence analyzed primarily provide geographical knowledge and general information about the environment, without a focus on the dangers of drought, Syria’s water crisis and its effects on the lives of the population in the future. They do not cover the available water sources of each region of control or the challenges Syrians face in accessing safe drinking water.

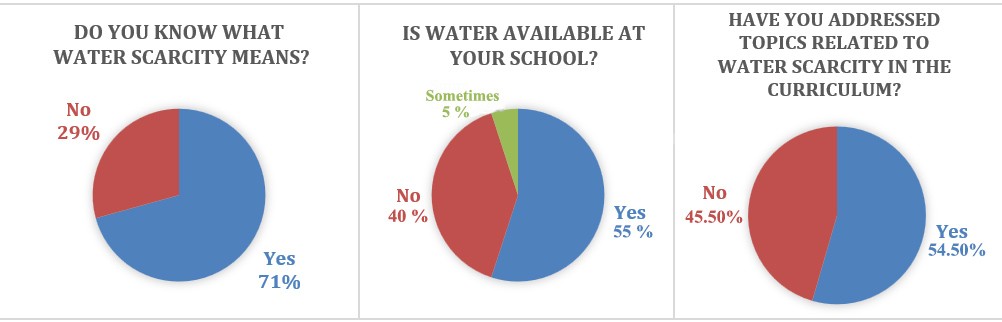

Of the 60 primary school students surveyed by reporters across the three areas of influence, 54.5 percent believe that the curricula they are taught do not provide them with enough knowledge about water problems. This is consistent with the curricula analysis, which showed a lack of focus on decreasing water resources as well as topics related to sustainable development and global solutions to confront water crises.

Answers provided by 60 primary school students in government, opposition and AANES areas surveyed about how the curricula in their areas address water issues, 2023 (Simav Hesen/Dahab Noura)

Only one of the 60 students said her teacher referred to new crises and wars in which water could be used to affect Syria. She studies in AANES areas, and said the teacher asked students to think about a decision they could make as future decision-makers to address water wars.

This answer intersects with answers to the questionnaire that was distributed to 12 teachers in the various areas of control. Some 24 percent of teachers said they provided additional information related to water-related topics, and all agreed that students are not sufficiently aware of the water crisis and its future risks.

In the students’ questionnaire, most of the answers indicated that the main topics they studied during the primary stage were related to: the dangers of wasting water, desertification, the importance of agriculture and water’s role in it, drought, rain scarcity and some information about Syria’s water geography.

While students mentioned some information related to the impact of water on human health, they were not taught anything about possible solutions to confront water crises and wars, or about their economic impact. The majority of students said that the main water issue in their areas is a lack of availability, which they attributed to power cuts without indicating other reasons.

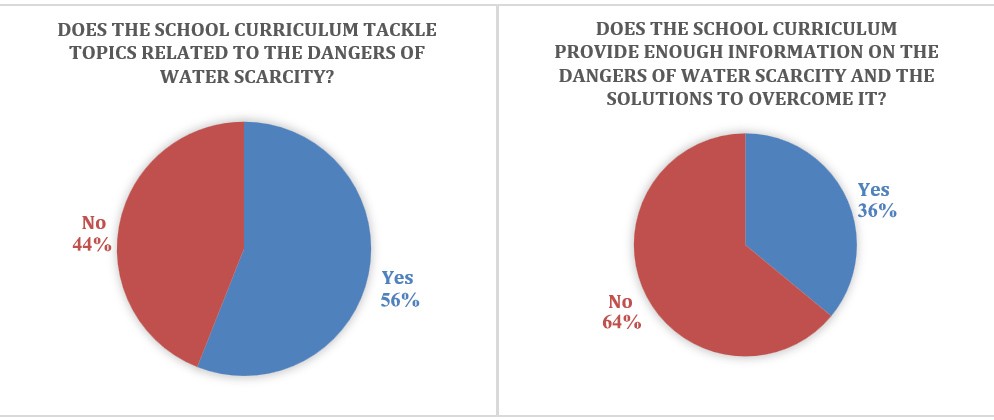

In this context, 44 percent of the surveyed teachers answered “no” to the question: “Does the school curriculum tackle topics related to the dangers of water scarcity?” Meanwhile, 64 percent answered “no” to the question: “Does the school curriculum provide enough information on the dangers of water scarcity and the solutions to overcome it?”

Answers provided by 12 teachers in government, opposition and AANES areas about how the curricula in their schools address water issues, 2023 (Simav Hesen/Dahab Noura)

The surveyed teachers pointed to several barriers to forming appropriate student awareness of Syria’s future water crisis, including:

- The curriculum is not broad enough.

- The water crisis is integrated into other crises, without enough space allocated for it, and there is a lack of materials and activities related to drought and its proposed solutions.

- Not explaining the systematic policies of countries that have water sources but use them as tools of war against other countries.

- Not updating the curriculum to reflect climate changes in the world.

- Lack of appropriate educational materials and lack of awareness sessions in this field.

- Extensive focus on the problem, while tackling solutions only briefly in one or two sentences per lesson. Students do not feel responsible, because they consider themselves far from the crisis, thinking that drought is in Africa, as depicted in the curriculum.

- Lack of field trips.

- Relying on traditional means of explanation in textbooks.

This information indicates that today’s students, who will be between 35 and 42 years old by 2050, are not being given the tools they need to deal with a disaster on the scale of the drought threat facing Syria. Their curricula are not adequately preparing them or prompting them to think about how to face this crisis and search for solutions.

The official stance

The official stances of educational authorities on the issue of drought resemble one another across different areas of influence, as does the weak approach of their curricula towards tackling future risks.

When presented with the reporters’ findings regarding the AANES curriculum, Darsheek Khalil, a member of the Monitoring and Evaluation Committee at the AANES Curriculum Management Association, said: “There is no doubt about the importance of water for sustaining life and that it comes before energy, and our curriculum must deal with this topic—but from the perspective of water rationalization, its role, importance, and preservation. As for addressing the water problem in the primary and middle school, it is very early. It could be addressed in secondary school in an age-appropriate way..”

Khalil’s response contradicts psychological studies that indicate that children’s awareness is formed early on, from the age of three, with each developmental stage related to the way information is presented.

Psychological and educational research shows that schools play a major role in shaping awareness about a specific topic, by stimulating a child’s imagination with the tools they prefer, such as cartoons and television shows. Teachers surveyed emphasized a scarcity or complete lack of visual aids in their lessons.

“We will try to avoid all errors in our curriculum, in the development process that we are undertaking,” Khalil said, “including the book Society and Life, to take the topic of water into account according to what the existing committees deem appropriate as a scientific subject.”

Ammar M., a member of the SIG Curricula Committee, said that the opposition government’s curriculum has not changed since 2013. He said the information it contains was appropriate for the past years, but acknowledged that “it is no longer valid.” From his perspective, “the period for amending curricula should range between seven and ten years,” which has not happened.

He also acknowledged that the SIG curriculum does not include the effects of drought on the environment, humans, animals and public health. Building awareness in areas where the SIG curriculum is taught happens in several ways, he added, including “providing specialized content, scientific activities, interactive teaching, field visits, live examples and awareness by participation.”

However, the examples he mentioned do not reflect the content of the curriculum analyzed by reporters. They also contradict the answers given by teachers who mentioned a lack of interactive tools and said information from outside the curriculum was not used.

In turn, an education supervisor from the Syrian government’s Ministry of Education, defending the curriculum, pointed out that “global curricula are amended every five years, and the Syrian curricula are constantly updated. Each grade contains age-appropriate topics related to water from first grade to 12th grade.” She stressed that “Syrian curricula are built on the topics of sustainable development and active citizenship.”

The response of the supervisor, who requested to stay anonymous, also does not match the findings of the reporters’ analysis, or the answers of the teachers in the areas controlled by the Syrian government. When asked about the curriculum’s coverage of sustainable development topics, they responded it was “insufficient.”

Determining the amount of lessons related to water depends on “ “the national standards document that is issued before starting to prepare curricula, and this is reviewed every five years.” This indicates that curriculum in the Syrian-government-controlled areas did not take into account climate changes in its latest update.

In response to not including the economy or water conflicts in topics taught about Syria’s water crisis, she said “primary school students cannot understand this.” She added, “children’s awareness is not only the responsibility of the school, but also their parents.”

While journalists, researchers and civil society are preoccupied with the critical water situation Syria faces by 2050, and the world talks and holds conferences about future water wars driven by climate change, this issue remains largely absent from Syria’s divided education system.

Omar, Ward and their fellow students in Syria remain without a minimum level of health education, with no educational plan to equip them to confront future risks. In the meantime, they do not know whether the next glass of water they drink will infect them with cholera or not.

This is one of six reports produced as part of an investigative journalism training program across various spheres of influence within Syria. Syria Direct is publishing the final reports in cooperation with the Syrian organization that conducted the training.

This report was produced in Arabic and translated into English.