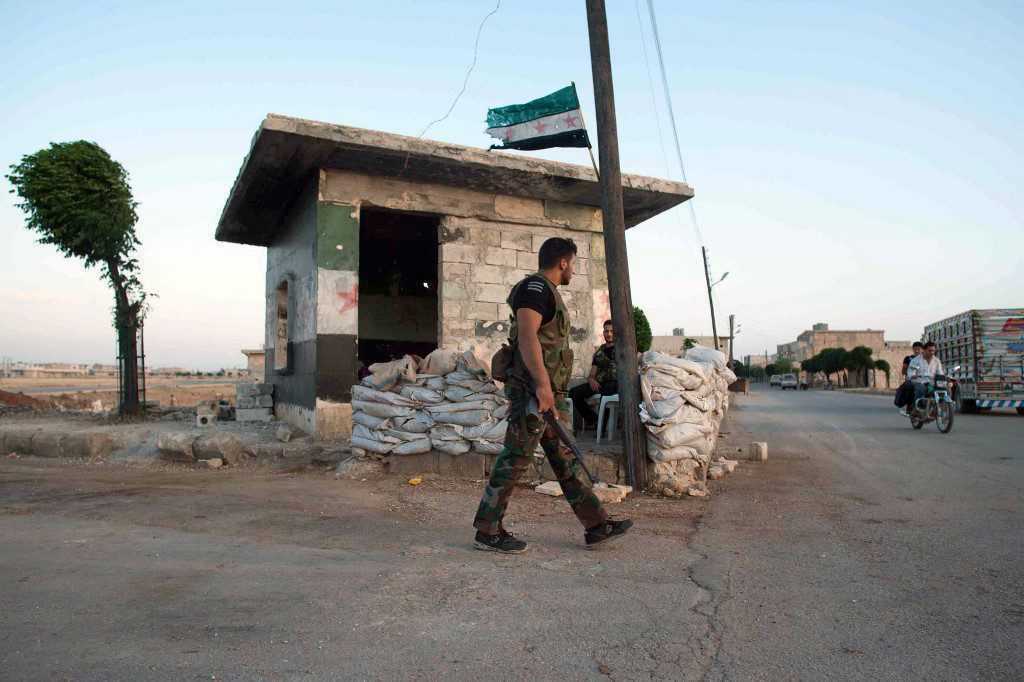

Missing in action: What happened to the once prominent Free Syrian Army?

Over the course of the war, internal and external factors have led to the erosion of the Free Syrian Army that was once the protector of civilians against the Assad regime forces.

24 March 2021

AMMAN — “Sorry, I don’t have time. I work from seven in the morning to 10 at night.” This was the message Syria Direct received from a Syrian officer who had defected from the government forces, become a military commander in an opposition faction based in Idlib province’s countryside, and eventually ended up in Turkey.

“I work at a grocery store to feed my kids. Maybe this summarizes what became of the Free [Syrian] Army,” the former officer concluded.

Scattered local groups

In reaction to the Assad regime’s brutal response to the peaceful demonstrations in the early months of the Syrian uprising, small local groups began to form – armed with hunting weapons, rifles, pistols and even knives – to deter government security forces and their allied shabiha (thugs) from attacking protesters and rebelling areas.

Simultaneously, the Syrian regime was “trying to drag the revolution into taking up weapons,” defected Colonel Abduljabbar al-Akidi said. “The military choice wasn’t the Syrian people’s.”

The taunts were evident in Bashar al-Assad’s first speech after protests broke out in the southern province of Daraa on March 18, 2011. He began with “many accusations against the revolution, by talking about terrorism, jihadists and Al-Qaeda,” al-Akidi told Syria Direct. He “said if you want war, we’re ready for it.”

On top of daily killings and targeting demonstrators, “the regime posted videos of rape, especially in Daraa and Homs, to incite the people and drive them to take up weapons to defend their honor and dignity, as well as the demonstrations,” al-Akidi added.

The defection of Lieutenant Colonel Hussein Harmoush from the army on June 9, 2011—the first military officer to do so—was a turning point in the course of the revolution’s military mobilization. After moving to Turkey, Harmoush founded in July 2011 the Free Officers Brigade, the first militant opposition body and the nucleus of the Free Syrian Army (FSA).

This new experiment in a country known as “the kingdom of silence” was not organized in a disciplined way. “From the beginning of the revolution until mid-2012, the military mobilization stayed scattered, unorganized and local, until military councils emerged in each province,” al-Akidi said,

However, “that state of chaos and disorganization with scattered and diffuse groups was a positive factor that helped protect these groups and their members,” according to Wael Alwan, a researcher at the Turkey-based Jusoor Center for Studies who was previously the spokesman for the opposition-affiliated Failaq al-Rahman in East Ghouta. “When the regime detains a person, he would only know in a limited way about the whereabouts, movements, location and working method of his group.”

After the formation of the Joint Command of the Revolutionary Military Councils in Syria in September 2012, “work started to be more organized. Defections increased and became more frequent in all regions, and [Assad’s] army began to wear thin. It was no longer prepared, and many barracks were liberated and weapons, including heavy weapons, seized,” al-Akidi said.

Increased defections in the government army’s ranks “accelerated the formation of the [opposition] factions, because the defecting [officers and soldiers] announced that they would not only leave armed work with the regime in protest of its actions but that they would also defend the demonstrations and protect them with weapons,” Alwan said. This “created balance, to some extent, in the sense that the regime was no longer able to enter any city any time it wanted to victimize its people.”

“Internal and external conditions were in favor of the [Islamist factions] growth and becoming a cancerous disease”

The Islamist dilemma

The FSA’s growth coincided with “the Assad regime releasing the Islamists from its detention centers, a large portion of whom needed a very long period of recovery,” according to Alwan, “from the psychological pressure, confinement and torture they were subjected to.”

“The regime caused an increase in some of [the Islamist prisoners’] extremism, malice and hatred of their surroundings and everything, as a result of the pressure and torture,” Alwan explained. “The regime knew that releasing them would Islamize the revolution; not the normal and natural Islamization, but rather of extreme radicalism and terrorism, which would negatively impact the [opposition] factions and their movement in general.”

Due to “public sympathy for religiosity in the Levant, many revolutionary youths were deceived by the slogans of these extremists,” Alwan added, “weakening the role of the defected officers and the political, intellectual and cultural elites.”

Further, extremist organizations “received huge support in comparison to the [FSA] factions, which were vulnerable to looting and robbery by the Islamist factions then,” Alwan said. Thus, “internal and external conditions were in favor of the [Islamist factions] growth and becoming a cancerous disease; slowly devouring the FSA factions in many regions.”

Al-Akidi echoed a similar opinion, comparing the “transnational Islamist organizations” to “a poisoned dagger stabbed into the chest of the revolution.”

Jabhat al-Nusra’s (now Hayat Tahrir al-Sham) declaration of its affiliation with Al-Qaeda in April 2012 was a “strong blow to the Syrian revolution, as it coincided with international discussions on supporting the FSA and providing it with quality weapons,” al-Akidi said. “In my opinion, it was no coincidence that [HTS commander, Abu Muhammad] al-Jolani’s announcement coincided with this conference, especially since support stopped following the declaration.”

At the end of 2013, another turning point in the revolution and FSA’s military operations came when the so-called Islamic State (ISIS) invaded large swathes of FSA-controlled territory and eliminated their leaders and forces, including defected officers.

This caused the “revolutionaries to put confronting the regime on the back burner,” al-Akidi said, “to protect their villages from ISIS and stop the organization’s creep into more liberated areas.”

In Syria’s southern Daraa province, Jabhat al-Nusra’s abduction of Colonel Ahmad al-Nemah, the commander of the opposition Military Council in Daraa, was a turning point for the FSA factions in the province, according to a former military commander in the opposition factions there.

“Al-Nemah’s kidnapping and disappearance [in May 2014] sent some of the FSA factions in Daraa off course,” the source told Syria Direct on condition of anonymity because he still lives in Daraa. “Al-Nemah had been leading the military council, receiving support and meeting with the Friends of Syria [an international collective of pro-opposition countries and bodies] by himself. With his abduction, every faction came to have an external representative receiving funding and meeting with supporters, which caused some to go astray and be bought.”

“This incident wasn’t spontaneous or not externally planned,” the source added. “Some supporting parties wanted to get rid of the negotiation process with one person and move to direct coordination with the factions on the ground.”

Self-inflicted setback

Internal factors were central in limiting the role of factions and contributed to their retreat. According to Alwan, these factors include “lack of or failure to build competent leaders, as well as intra-conflicts and disputes, which the Islamist factions were the main initiators.”

“Jihadist factions are characterized by rapid fragmentation, division and takfir [declaring others to be apostates],” Alwan added, “[so] there was no space to appeal to discussion and dialogue, but rather each faction fortified itself with weapons.”

On top of that, “Jabhat al-Nusra had a project—regardless of its content—and maneuvered and tried to achieve what it wanted. So today it still exists,” according to Abdulbaqi Hamdan (a pseudonym), a former commander with Nour al-Din al-Zinki Movement, a former opposition faction in northern Syria, “while some FSA factions’ lack of a project caused them to disappear.”

“The revolution bounded the FSA factions together, [but] it is just a general framework. There was no unified structure or organizational state, nor management of risk, challenges and obligations. So, for example, if an area was captured by the regime, the rest of the factions would not care, but rather say ‘we’re fine.’”

Antagonism between factions after any merger or formation of an operations room compounded this problem. But al-Akidi saw this as “natural” and “part of the labor of the military experiment that we are going through for the first time.”

“Mergers and formations were driven by seeking support, and with its absence, the factions would move to merge with another group that could provide it. However, the inclination for power among some of the commanders was a reason some new formations appeared.”

Further, the continuous support to “certain factions” negatively impacted the “formation of a general staff for the opposition factions and a ministry of defense belonging to the interim government,” according to al-Akidi. “You cannot have authority over these factions, especially in the absence of organization and real military discipline, so long as the funding does not pass through you.”

Exacerbating the situation, officers who defected from the regime were not given a real role in the FSA factions. “They were under the command of either a sheikh from Islamist groups, who did not understand anything about the military, or people from other professions in other factions: engineers, doctors and teachers,” according to Alwan. “The officer found himself obliged to carry out unprofessional orders, disastrous orders from non-specialists and, little by little, began to distance himself and withdraw.”

Also, “Islamists’ treatment of the defected officers as though they were raised by the Baath [party], led to excessive sensitivity among them. This greatly contributed to their reluctance to have any role in leading the factions. This badly affected the latter’s performance on the battlefield and their management of the liberated areas,” Alwan added.

“International support for the FSA all but stopped in 2016. Even before then, this support was small; just enough for the revolution to continue but not to be victorious”

External support or deceit?

Nine years ago, Nour al-Din al-Zinki took over a west Aleppo countryside town using just four rifles and a 12.5mm machine gun, Abdulbaqi Hamdan said. On the contrary, when opposition factions came to possess heavy weaponry and equipment, they could not match what they had achieved during the first years of the revolution.

“The transformation of opposition factions into this form, without agency, is normal and expected in the course of revolutions in which the army or military forces stand with the oppressive regime,” Alwan said.

Defection from the regime military and intelligence apparatuses was “very small,” compared to those who stayed with the regime, he added. Thus “confrontations become a zero-sum game, resulting in many victims and leading to neither victory nor defeat. In many cases, both sides come out of the battle defeated; no party reaches its goal.”

“Regional and international powers will soon be able to intervene widely in such cases,” Alwan said. And in the Syrian case, “all parties have become subject to external interference.”

However, “international support for the FSA all but stopped in 2016,” according to al-Akidi. “Even before then, this support was small; just enough for the revolution to continue but not to be victorious, due to the international community’s lack of confidence in the FSA and fear of the prevail of Islamists and jihadist factions.”

Alwan agreed, saying that “the external parties were able to bring the battle to an end, but they didn’t want that. Rather, they left the factions vulnerable to regional and international bargains and blackmail that have brought them to where they are now.” On top of that, “some countries provided money and support to factions with beards and turbans to support specific jihadist tendencies,” which includes “leading the revolution astray, and not supporting it,” he said.

On the other side, the regime’s Iranian and Russian allies put their total weight behind it. “The broad, large Russian support had no equivalent for the rebels,” according to Alwan. This situation deepened with “the American support for other parties, such as the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) that is hostile to the other two [the FSA and the regime].”

This was “a crucial transformation that made the local players unable to continue on their own or with their own capabilities, and gradually made them lose everything, even the margin of internal decision-making.”

Is the FSA finished?

“The FSA was not just a name,” Hamdan said. It “was tied to several things, and when it lost them, we started to lose the FSA.” The name “Free [Syrian] Army was connected to liberation and the state of security and stability people experienced in its areas.” It belonged “to the community itself. It was the child of this [Syrian] society. It was impossible to see a fighter harm civilians and the people of his village at that time. When all that went away, and the FSA was unable to fulfill the promise to unite and be an organized army, it began to erode.”

In parallel with Syrians’ tragic situation in the camps, the signs of arrogance began to appear in some military commanders, creating “a gap between society and the factions’ leaders,” according to Hamdan. “Syrians were waiting for the Syrian National Army to appear, which is meant to be a continuation of the FSA in a united form.” But “even as an institution, the community does not cling to it today because it wants the National Army to respect it, reorganize itself, and protect people from bombs, but it is unable to do so. And if not for the Turks, the Russians would have reached the border. For that reason, the legitimacy of the FSA’s presence has disappeared. The FSA has disappeared.”

In the same vein, Alwan said, “The FSA became a name with no meaning when the Islamist and radical factions claimed to be part of it.”

“The FSA is, by definition, groups of officers and defected forces, later joined by civilian volunteers to protect the revolution and rebel areas. But when this name became general, a card that anyone can carry and claim, it no longer had a meaning in the Syrian revolution. It began to disappear until it vanished.”

Conversely, al-Akidi asserted that “a large part of the [Turkish-sponsored Syrian National Army] factions represent the FSA.” Despite the presence of “those who deviated in different directions and became tools in the hands of others and mercenaries, the lion’s share of the factions that exist today are an extension of the Free [Syrian] Army.”

This report was originally published in Arabic and translated into English by Mateo Nelson.