Snowball effects of Lebanon’s economic crisis fall hard on Syrian children

Syrian children are among the hardest hit as Lebanon’s public education system falters under the weight of economic crisis and dwindling funding.

30 October 2023

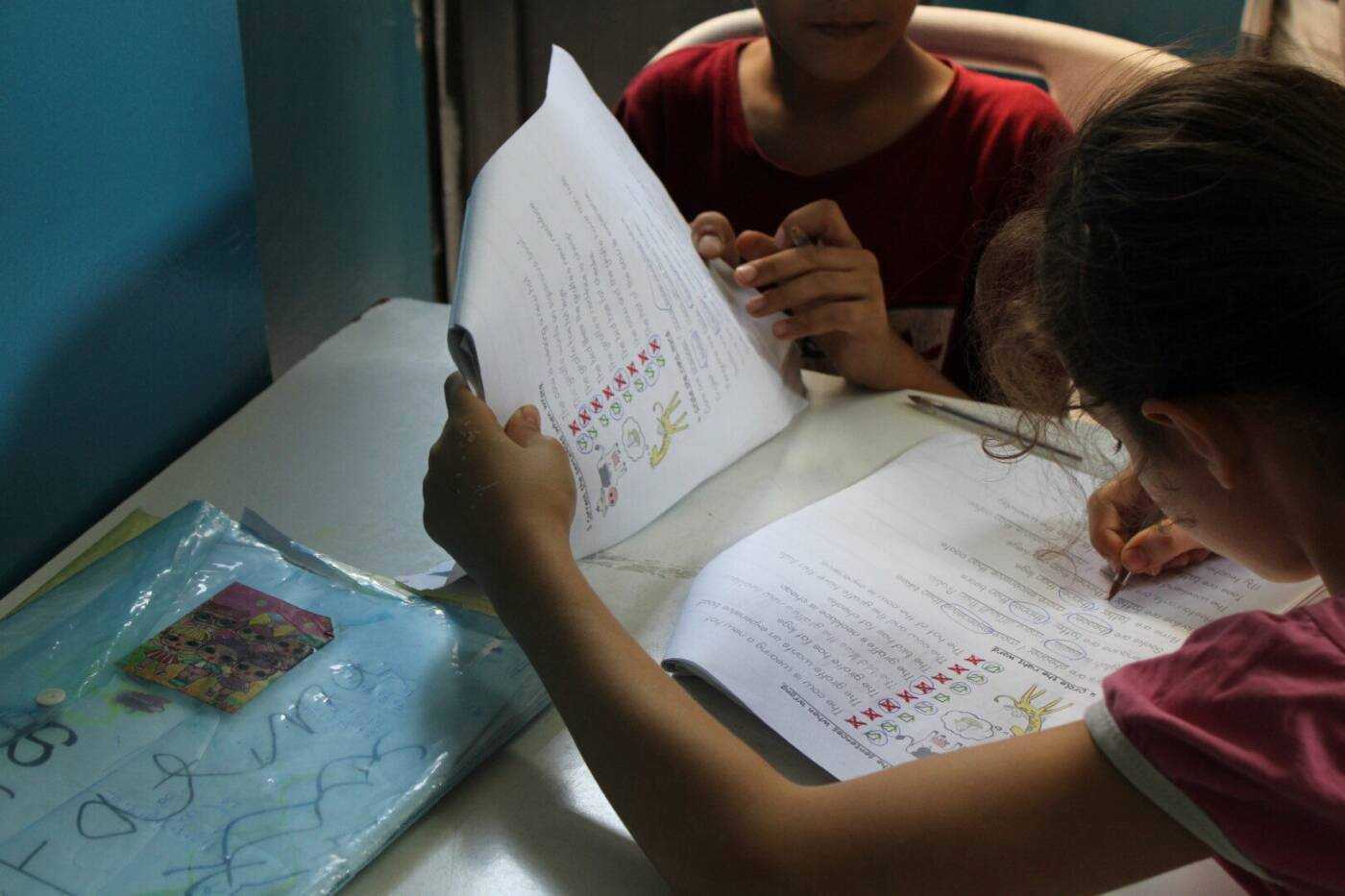

BEIRUT — At a learning center nestled in Beirut’s Hamra neighborhood, a cacophony of voices rang out one day in October. Inside, children pointed to giraffe, elephant and octopus cut-outs pasted on the walls, shouting animal names out loud in English. A few older children sat nearby with volunteer teachers, completing workbooks of English activities while others drilled math problems.

The center, 26 Letters, currently offers alternative education to 131 Syrian refugee students in Lebanon’s capital city. “It’s the place I felt safe and welcomed,” the center’s youth director, 19-year-old Issa Mustafa, told Syria Direct. Issa began as a student at 26 Letters soon after he fled Syria in 2016.

Because Issa, like the vast majority of Syrians in Lebanon, does not have legal residency, he was not able to take the exam required to begin secondary school. 26 Letters, a small, volunteer-based nonprofit founded in 2015, was the only education option he had left, he said.

Hundreds of thousands of children and youth, like Issa, have fled from Syria to neighboring Lebanon since the war began more than a decade ago. Lebanon currently hosts the highest number of refugees per capita in the world, while also facing one of the world’s most severe economic crises, caused by financial mismanagement and corruption by its sectarian ruling elite.

Four years into the crisis, Lebanon’s state coffers are bone dry, leaving the public education system in tatters. The estimated 660,000 Syrian refugee children living in the country are among those hit hardest. When funding for schools and teachers runs low, services for Syrians are often the first to be cut.

This year in Lebanon, the start date for Syrian students—most of whom attend “second shift” afternoon classes in public schools—was pushed back to at least the end of October, UNICEF Chief of Education in Lebanon, Atif Rafique, told Syria Direct. Lebanese students began their classes on October 9, while registration for second-shift Syrian students is set to begin on October 30.

At 26 Letters—which is not an official school—more than 4,000 children are on the waiting list to take courses, the center’s founder, Janira Taibo, told Syria Direct. Most are Syrian, while the list also includes a number of Lebanese children and children of other nationalities.

Syrian children face huge obstacles to school enrollment in Lebanon. More than half of all Syrian children, ages three to 18, are not in school and many have never stepped foot in the classroom, Rafique said. And more than 99 percent of all non-Lebanese students, most of whom are Syrian, are not enrolled in secondary school past the ninth grade.

UNICEF only subsidizes public education in Lebanon until the ninth grade, the compulsory years. Afterwards, “you have a real cliff for the most marginalized,” Rafique said, with few non-Lebanese students continuing to higher grades.

“This is devastating for children and their life chances,” the UNICEF education chief added.

A volunteer teacher instructs a student at 26 Letters, a learning center in Beirut’s Hamra neighborhood, 04/10/2023 (Hanna Davis/Syria Direct)

At work, out of school

In one of Beirut’s Palestinian refugee camps, Sabra—where many Syrians also live for affordable housing options—Mahmoud al-Ali, 46, lives in a one-room home with his wife and four children: 14-year-old Kawthar, 16-year-old Fatima, 18-year-old Sidra and a two-year-old boy.

In 2012, al-Ali’s family fled Syria’s opposition-held northwestern Idlib province. More than a decade later, Idlib continues to face bombardment and attacks that make it unsafe to return to. But life in Lebanon has not been easy.

“We’ve faced all kinds of racism, in all of its forms,” Mahmoud told Syria Direct. “We’re going through a lot just because we’re Syrian,” he said. “Why? We are human beings. We are good people.”

Mahmoud’s two eldest daughters, Fatima and Sidra, dropped out of school when they were 12 and 15, respectively, because they did not have legal residency papers, he said. The cost of school materials was an additional barrier. Some 90 percent of Syrian refugees in Lebanon live in extreme poverty, compared to 36 percent of Lebanese citizens.

While both Fatima and Sidra are officially registered as refugees with the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), their residency in Lebanon has expired. To renew it, they would need to return to Syria to get a personal identification card or civil registry document—an option that is out of the question, Mahmoud said.

It has become “increasingly difficult for Syrians to renew their residency papers,” Ramzi Kaiss, a researcher for Human Rights Watch in Lebanon, told Syria Direct. As a result, some 83 percent of Syrians in Lebanon do not have legal residency.

Even for Syrians who do have up-to-date identity documents, many struggle to afford $200 annual renewal fees. Since 2015, Lebanon has prevented Syrian refugees from registering with UNHCR. So, to get legal residency outside the UN agency, a Lebanese sponsor—with the approval of authorities—and the high renewal fee are required, according to a 2021 Brookings report.

Instead of going to school, Fatima and Sidra now work at a clothing shop near their home in Sabra. Most weeks, they work 12 hours a day, seven days a week, bringing home just $25 each—around 20 cents an hour.

Mahmoud fears that his youngest daughter, Kawthar, could also be forced to drop out of school one day. “The situation is so hard. We want to leave,” he said. “I want my children to finish their studies, go to school, and achieve their dreams.”

‘Coercive measures’

Over the past several months, Lebanon has seen a “marked intensification” of government resolutions, security protocols and provocative media directed at Syrian refugees in the country. Life in Lebanon, as well as official procedures such as school enrollment, has grown increasingly difficult for Syrian refugees as a result.

“There’s certainly a rise in anti-refugee sentiment that’s being propagated by Lebanese officials,” Kaiss said.

Media campaigns organized by Lebanese politicians, which blame Syrian refugees for Lebanon’s ongoing economic crisis, have caused public tensions to escalate and has accumulated into increased acts of violence against Syrian refugees overall, according to the Access Center for Human Rights (ACHR), a human rights organization based in Beirut and Paris.

On October 5, Lebanon’s caretaker Interior Minister Bassam Mawlawi issued a series of memos addressed to the Internal Security Forces (ISF) and the Beirut governorate, calling for a crackdown on Syrian nationals in the country.

Mawlawi directed security forces to stop “motorcycles or mopeds driven by Syrians who don’t have a residence permit,” enforce a ban on donations related to displaced Syrians that might “justify their staying in Lebanon” and combat street begging, English-language Lebanese daily L’Orient Today reported.

One day before issuing the directives, the minister had announced that Lebanon “will not allow the random Syrian presence,” adding that the government was working to “stand against the immense harm inflicted on Lebanon, the Lebanese people, and Lebanese demographics as a result of the chaos and unacceptable behavior due to the Syrian displacement.”

Since the start of the year, the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) have carried out an unprecedented wave of arrests and deportations of Syrians. Hundreds of people have been sent back—including some registered refugees—regardless of the risks of persecution they face.

“Authorities are ramping up their scapegoating against vulnerable populations, as a way of avoiding their responsibility for the dire economic crisis, instead of taking the needed steps to put the country back on the path to recovery,” Kaiss said.

In September, caretaker minister Mawlawi called on municipalities across Lebanon to conduct an “immediate survey of displaced Syrians” and remove all “violations,” praising municipalities that had already cracked down, Arabic TV channel Alhurra reported.

At the end of the month, Maan Khalil, mayor of the Ghobeiry municipality in Mount Lebanon governorate south of Beirut, posted on X (formerly Twitter) about the closure of more than 50 shops and restaurants “rented to and employing foreigners working in violation of the law.” Days later, 86 motorcycles, tuk-tuks and trucks were also seized due to foreigners driving “without registration,” Khalil posted.

The Ghobeiri municipality also issued a statement to school principals in early October, requesting the names of all enrolled foreign students and emphasizing that public schools were not to admit students without legal residency or risk being closed.

On paper, Syrian students may enroll in public schools up to the ninth grade without legal residency, though this is not always the case in practice. Some schools require valid residency permits, while others request different types of documents, like birth certificates, UNICEF’s Rafique said.

Lebanon’s Minister of Education Abbas al-Halabi pushed back on “the Ministry of Education being accused of racism and inhumanity” in a statement last month, adding that he has submitted a draft law to the Council of Ministers every school year to ease school registration requirements.

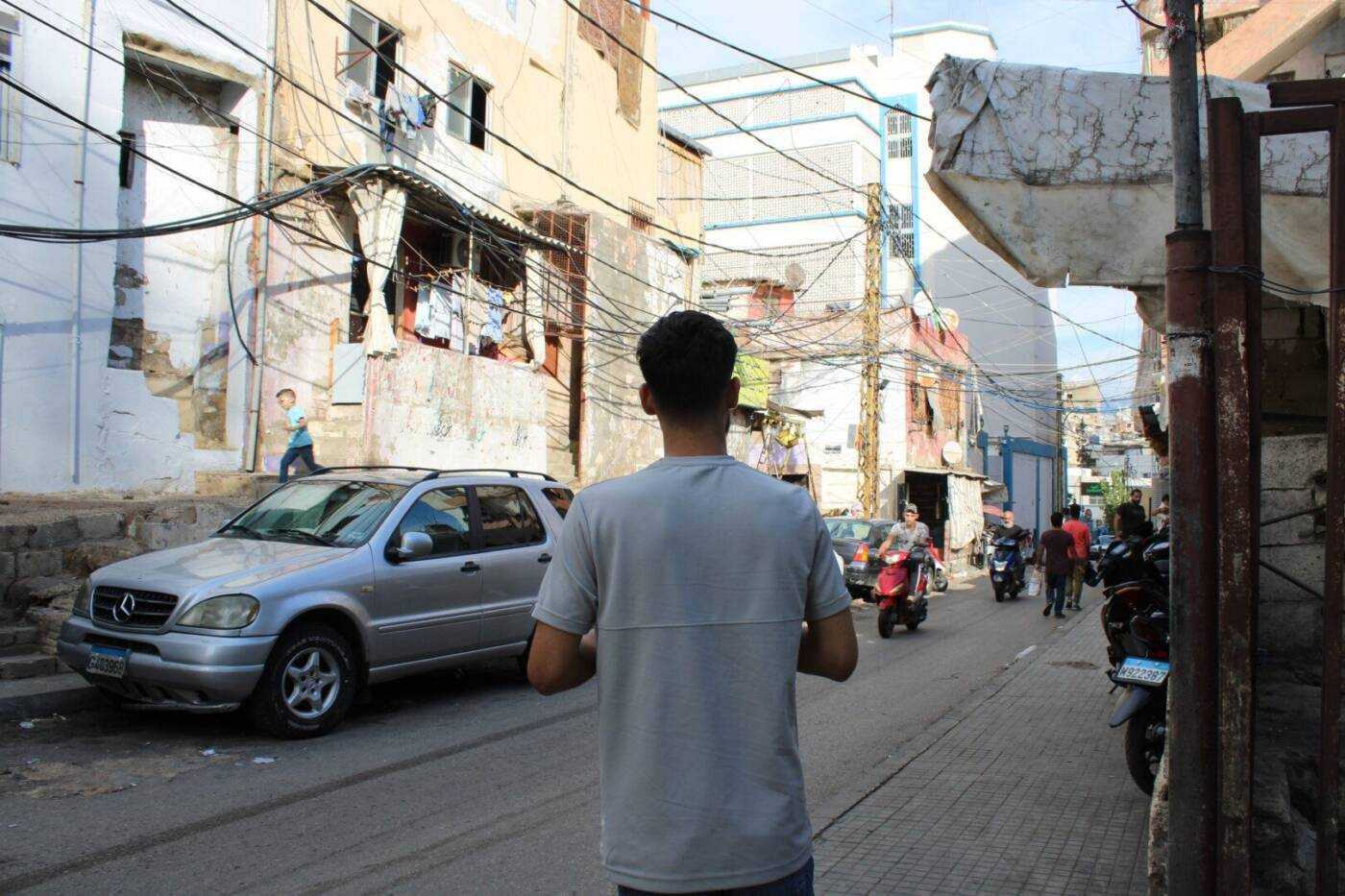

Muhammad al-Hassan, 21, stands outside his home in Beirut’s Sabra refugee camp, 04/10/2023 (Hanna Davis/Syria Direct)

Dropping out

Not far from Mahmoud’s home in Sabra, 21-year-old Muhammad al-Hassan lives with his mother and two younger siblings. His family is also from Idlib, and fled to Lebanon in 2011. Muhammad’s aunt and her infant son were killed in the fighting four years later, leaving Muhammad’s mother terrified to return.

Muhammad attended school in Lebanon, but dropped out when he was 16 to work and support his family. Still, “I love studying,” he said.

This year, Muhammad decided to resume his education, but could not reenter the public school system because he had been absent for more than two years—another barrier that thousands of Syrian students face.

Private school was his only option, at a cost of hundreds of dollars per semester. To save up, he found a new job at Spinneys, an upscale supermarket chain, in Achrafieh, a more affluent area of Beirut, earlier this month.

Soon after, however, Muhammad put his job on hold in order to stay close to home. His residency permit expired on October 12, and he feared being swept up in Lebanese authorities’ crackdown on Syrians.

His fears were realized on October 24, when he was arrested while driving his moped through a checkpoint. He says he was held for 24 hours, threatened with deportation and not allowed to inform his family of his whereabouts. His moped was also seized, though he managed to get it back after hiring a lawyer, he said.

“When I see a checkpoint, my heart drops,” he said. “If they don’t take me, they’ll take my motorbike.” Muhammad said a number of his friends have had similar experiences, and that some were beaten after they were arrested.

To avoid another run-in with the authorities, Muhammad has still not returned to work. A friend loaned him money for his first school payment, but when the next payment comes due, he worries he will have to put his education on hold once again.

“I am super, super scared,” he said.

Violence at school

Increasing hostility and violence against Syrian refugees in Lebanon has also trickled into classrooms, some Syrians say.

Last year, Muhammad’s mother volunteered to help with afternoon classes at a public school in Beirut, where she said she saw teachers carry out abusive punishments. The “psychological pressure” eventually led her to quit the position, she said. “It is really bad. They don’t teach, they are very racist. They threaten the kids,” she said.

Rafique, from UNICEF, said “violence is an issue across the school system” in Lebanon, though he did not differentiate between the treatment of Syrian and Lebanese students. “It is a significant issue, and it affects the demand for public education and the learning continuity for these children,” he said.

Kawthar, Mahmoud’s youngest daughter, who attends afternoon classes for Syrian students, told Syria Direct that her teachers are often angry and lash out at her. “If I tell the teacher to repeat the lesson, she gets angry and asks me why I wasn’t paying attention. She has hit me with a ruler on my hand,” she said. “This happens to us in the afternoon, because we are Syrian.”

Rafique said UNICEF offers psychosocial support to students and is trying to implement quality-training programs for teachers. However, he added: “the quality agenda becomes even harder when you have a demotivated workforce that can’t make ends meet.”

Teachers’ salaries in Lebanon have depreciated to a mere $90 per month, barely enough to cover transportation, amid the ongoing economic crisis. Frequent teacher strikes in response have also led to prolonged school closures.

UNICEF and the international community have provided billions of dollars in recent years to keep schools open in Lebanon, contributing about $140 per Syrian student and $18.75 per Lebanese child, according to a September report by Human Rights Watch. But these funds are drying up. A $200 million World Bank and UK grant that had covered previous schools is now exhausted, the rights organization noted.

“International funding is going down, including for education,” Rafique said. “For sure, international support is important, but frankly, it’s also about the government contributing its fair share and in an efficient way. Lebanon needs to make choices about investment in the public school system,” he added.

Dreams

For many Syrian children, their dream is to leave Lebanon. In Sabra, Kawthar dreams of one day becoming a surgeon. She shadows a doctor at a nearby clinic all day, six days a week, while she waits for school to start.

“She’s so smart,” her father said: “She says: ‘Baba, I want to become a surgeon’. But in this situation we are living in, how can she do this?”

“I really want to continue and complete my studies,” Kawthar told Syria Direct. “But in Lebanon, this is not possible. There is so much racism and the education is not good.”

Issa, the youth director at 26 Letters, has found a community in Lebanon where he feels safe. The rest of his family has not, and recently decided to return to Syria, despite the risks. “My father says it’s better we live in a dangerous place, than here with racism,” he said.

Issa is not going back with them. “I’m staying here, for 26 Letters,” he said.