Syria online: Digital archives reconnect a generation scattered by war

Digital archives are preserving crowdsourced testimonies of war and creating spaces where Syrians at home and in the diaspora can piece back together their history, shared culture and lived experiences.

20 August 2023

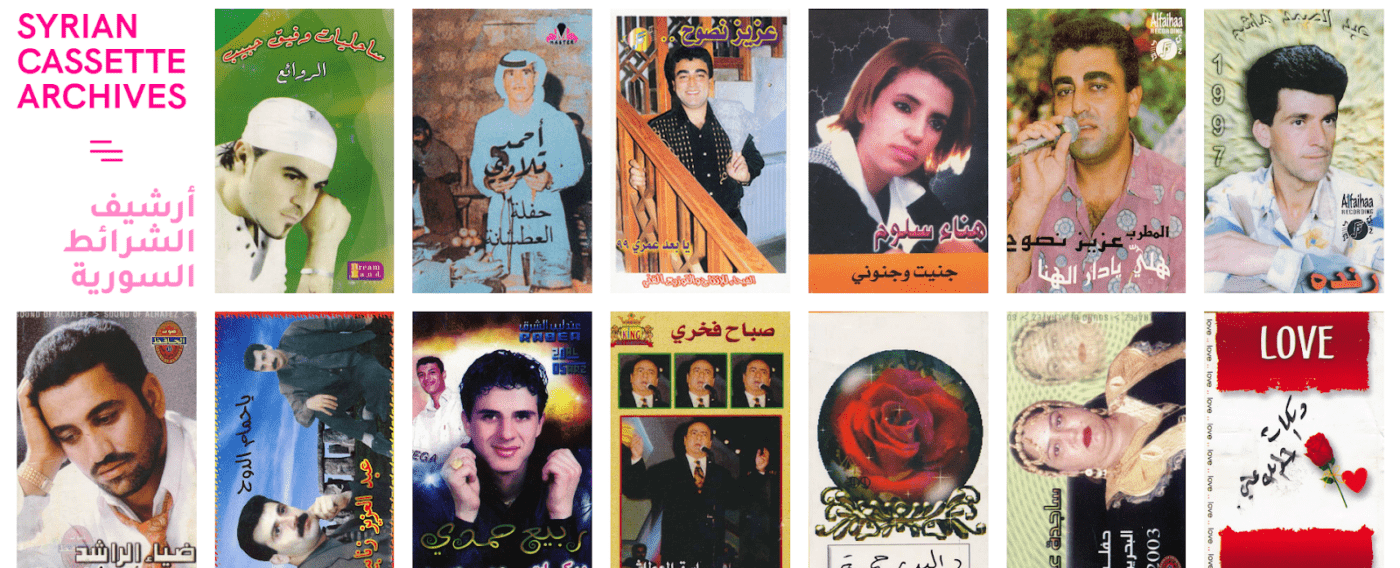

AMMAN, ERBIL — Rainbow fonts, thick mustaches, 1980s-style sunglasses, vibrant collages and fading portraits of beautiful divas form an eclectic gallery of cassette-tape illustrations on the website of the Syrian Cassette Archives, an online platform dedicated to preserving Syrian cassettes produced since the 1970s.

The archive’s cassettes contain a unique collection of hits, children’s music, folklore songs, Arabic classics and dabka rhythms. When clicked on, each cassette unleashes its tunes: melodious songs by Arab, Kurdish, Assyrian or Armenian musicians, rhythmic religious chants or the powerful voice of an Iraqi singer exiled in Syria.

The archive, which launched its website in early 2022, grew out of the private collection of Mark Gergis, an Iraqi-American musician, and is curated by Gergis and Yamen Mekdad, a Damascus-raised DJ. It is one of dozens of digital archives—large and small, private and crowdsourced—that have flourished online since the Syrian revolution began in 2011, each working to document a facet of the country’s history, memory and culture.

“There are several initiatives that aim at collecting and preserving crowdsourced archives of the Syrian uprising. Some of them are institutional and some of them are community archives,” Dima Saber, a researcher who has published several articles on Syria’s crowd-sourced archives, told Syria Direct. “Some of them look at artistic and creative memory, some look at human rights violations.”

Perhaps the most well-known of these, the Syrian Archive, documents human rights violations and crimes committed since 2011 through millions of crowdsourced photographs, videos and digital testimonies. Others—like the Cassette Archives, the storytelling platform Qisetna, the visual repository Creative Memory of the Syrian Revolution and websites Notah and Alkhashabeh—pursue another essential goal: holding on to different aspects of Syria’s scattered cultural landscape to ensure they remain accessible to current and future generations.

While each archive has its own goals, methods and abilities, they are part of a common effort and face similar challenges. For all, the time-consuming, methodical quest for documents and sources is often a race against time due to the fleeting nature of much of the content they seek to harvest.

Part of a poster for “The Whirlwind,” a play by Egyptian writer Mahmoud Diab performed in Syria in 1972, which has been digitized and stored by the Syrian Theater Archive – Alkhashabeh (Alkhashabeh)

Documenting war crimes and rescuing culture

People save and archive materials for a few reasons, Saber said. “One is that people archive for testimonial and historical values—because they want to preserve the stuff that they think is important. There’s also an evidential value, if they think it can be turned into evidence that can later be used in court, and there’s a creative value.”

The first two rationales drive the Berlin-based Syrian Archive, launched in 2014 to preserve digital content coming out of Syria during the revolution and war. Its collection includes videos documenting the chemical massacres carried out by the Syrian regime against civilians.

Over nearly a decade, the Syrian Archive has collected more than 5.2 million items—including texts, articles, images, videos and maps—related to Syria. It has also become a key source of evidence for investigators, journalists and human rights organizations working on the conflict.

“The purpose behind establishing this archive is to preserve the materials [documenting human rights violations],” Haneen Haddad, the archive’s research coordinator, told Syria Direct. “Some of them are very important evidence or sometimes the only evidence to a certain crime. So if it disappears, the memory behind this incident will disappear, and we will not be able to prove anything in the future.”

The archive regularly receives external requests for documents that have been deleted from other platforms where they were originally posted. Several sister archives were born out of this successful experience, covering conflict zones like Yemen, Sudan or Ukraine.

Alongside the Syrian Archive, other online repositories emerged in recent years—often led by Syrians in the diaspora aiming to preserve different aspects of the country’s history, culture and heritage.

“Any national identity has different components. Part of it is built around culture and artistic memory, and that part of our identity is now threatened,” Muhammad Amireh, programs officer at Douzan Arts and Culture, a Turkey-based organization working to preserve Syrian cultural memory, told Syria Direct. “After the huge number of people that fled out of the country, or claimed asylum, Syrian identity is really threatened to be demolished and lost.”

Douzan runs a few virtual archives that document different aspects of Syria’s artistic production, past and present: Notah, which archives music and folklore dances through music score sheets, research, records, videos and biographies of Syrian artists, and Alkhashabeh, which focuses on theater through recorded plays, playscripts, posters, brochures and other documents.

A 1972 performance of “The Whirlwind” in Syria, directed by Hussain Edlby (Alkhashabeh)

Often, the work done by these organizations troubles dominant narratives of Syrian culture that prevailed before the war. “Through our research, we found that there was a theater scene in each city in Syria – not only in Damascus. There was a theater scene in Suwayda, in Hama, in Salamiya…but some of those artists were not included in the picture that was shown to the audience outside of Syria,” Amireh said.

Online cultural archives consciously include the work of local and marginalized artists, reflecting the diversity of ethnic, religious, cultural and political currents that fed into Syria’s vast pre-war cinema, theater and music scenes. Notah has a special project focused on folklore songs passed down from one generation of farm workers to the next, and the Syrian Cassette Archives includes songs for children that may have no known authors, as well as religious sermons.

Connecting Syrians across borders and time

Much of today’s Syria-focused archival work is less about preserving the past than preparing for a shared future.

“I think there’s an important connection between being able to establish consensus on our collective past and being able to coexist and build a stable and peaceful future,” Saber said. “Archives can allow communities to build a shared understanding of their collective experiences and play a key role in building collective memory. I wanted to contribute to efforts that could avoid the same Lebanese tragedy—not reaching a consensus on the history of the Lebanese civil war—happening again in Syria.”

In order to develop a collective memory of the war, Syrians need access to shared historical resources, documents and evidence. The same is true of culture. With around one fourth of Syria’s pre-war population now living in exile abroad, many Syrian youth are growing up with increasingly tenuous connections to their own history and heritage.

“There’s a huge number of the new generation of Syrians who don’t know what Syria produced,” Amireh said regretfully. And those who would like to reconnect to their roots may not even know where to start.

“[If you left] Syria when you were around 10 years old, going to a new country as a refugee…and then you become interested in art production, most probably you’re going to be introduced [to it] in the new country that you are in now,” Amireh said. “What we are trying to do through our archives is to enable young Syrians and young artists to check out what Syrian art was like, and get inspired in creating new, modern, contemporary productions. Through the Notah and Alkhashabeh programs and archives, we are trying to open a space for people to dialogue, to discuss, to open their eyes to the history of Syria.”

Through their work, these organizations help piece back together fragments of an artistic landscape splintered by war and displacement. Douzan’s archivists apply a broad definition of “Syrian art” that encompasses work produced in Syria before and since the 2011 uprising, as well as creations by Syrian artists in exile. The organization also disseminates artistic productions and information through social media, trying to reach a broader audience of people who may not be familiar with Syria’s long theater or music history.

A race against time

Whether archiving visual evidence of atrocities or the legacy of Syrian artists, all of these initiatives are fighting an uphill battle against time and the partial fragmentation of Syrian society.

“At the archiving level, it’s been hard to find resources and reach out to sources, because some of the artists and producers have died,” Amireh said. But even material that has already been published online is at risk of disappearing overnight.

Social media platforms’ fast-changing policies are one of the main challenges these organizations face. “Any changes in the policies of social media platforms affect us a lot,” Haddad, of the Syrian Archive, said. “Changes can create bugs and other preservation challenges, so we are always racing to find a new technical solution.”

“We found a lot of Facebook pages and social media pages that are no longer active since three or four years,” Amireh said. “In such cases we try to contact the owners and archive the work that they published, because this page is going to be closed.”

In 2017, YouTube began to take down a massive number of videos deemed to contain graphic or inappropriate content, including many videos documenting war crimes in Syria. And in May 2023, Twitter announced that it would start removing inactive accounts, sparking concerns that content posted by activists who have been jailed, killed or disappeared would be lost to investigators.

“All of these challenges mean we are in a race with time to preserve and rescue this content before it is deleted,” Haddad said.

The Syrian Archive uses in-house software to download and save content from a list of what it deems to be credible online sources. This way, much of the content being produced from and about Syria is backed up on the organization’s own servers, where it can be recovered in the future even if the website or social media account that first shared this material is taken down.

But even automatic archiving cannot beat the speed with which algorithms—and increasingly artificial intelligence—identify “graphic” content and remove it from social media. “I want to emphasize that any content on social media platforms is not stable,” Haddad said. “Activists in any conflict area should not deal with social media platforms as servers, because they cannot ensure that this content will stay forever.”

Saber, now the program and impact director at Meedan, a nonprofit that supports independent journalism, media literacy and human rights efforts, is also working with members of the Syrian Archive on a new project called Syrian Digital Memory. The project will showcase some of the Syrian Archive’s videos alongside the stories of the Syrians who filmed them.

“There are different reasons why they do this, and one of them is this obsession with Hama,” Saber said, referring to the 1982 massacre committed by the Syrian army in Hama city in response to an uprising against the regime of then-president Hafez al-Assad.

Estimates on the final death toll in Hama vary. Indiscriminate bombings may have killed as many as 40,000 residents, but virtually no visual or historical evidence of the killings remains. A months-long media blackout and decades of public silence about the event left little for survivors to cling to, and no space to share their plight with other Syrians.

“This kind of haunts all the videographers we spoke to,” Saber said. “They say it should never happen again.”