‘There is no future for us in Iraq either’: Statelessness plagues Syrian Kurdish refugees

Thousands of Syrian Kurds remain stateless 60 years after they were stripped of citizenship. As refugees, they face unique asylum challenges, pushing them toward dangerous, informal migration routes.

14 September 2022

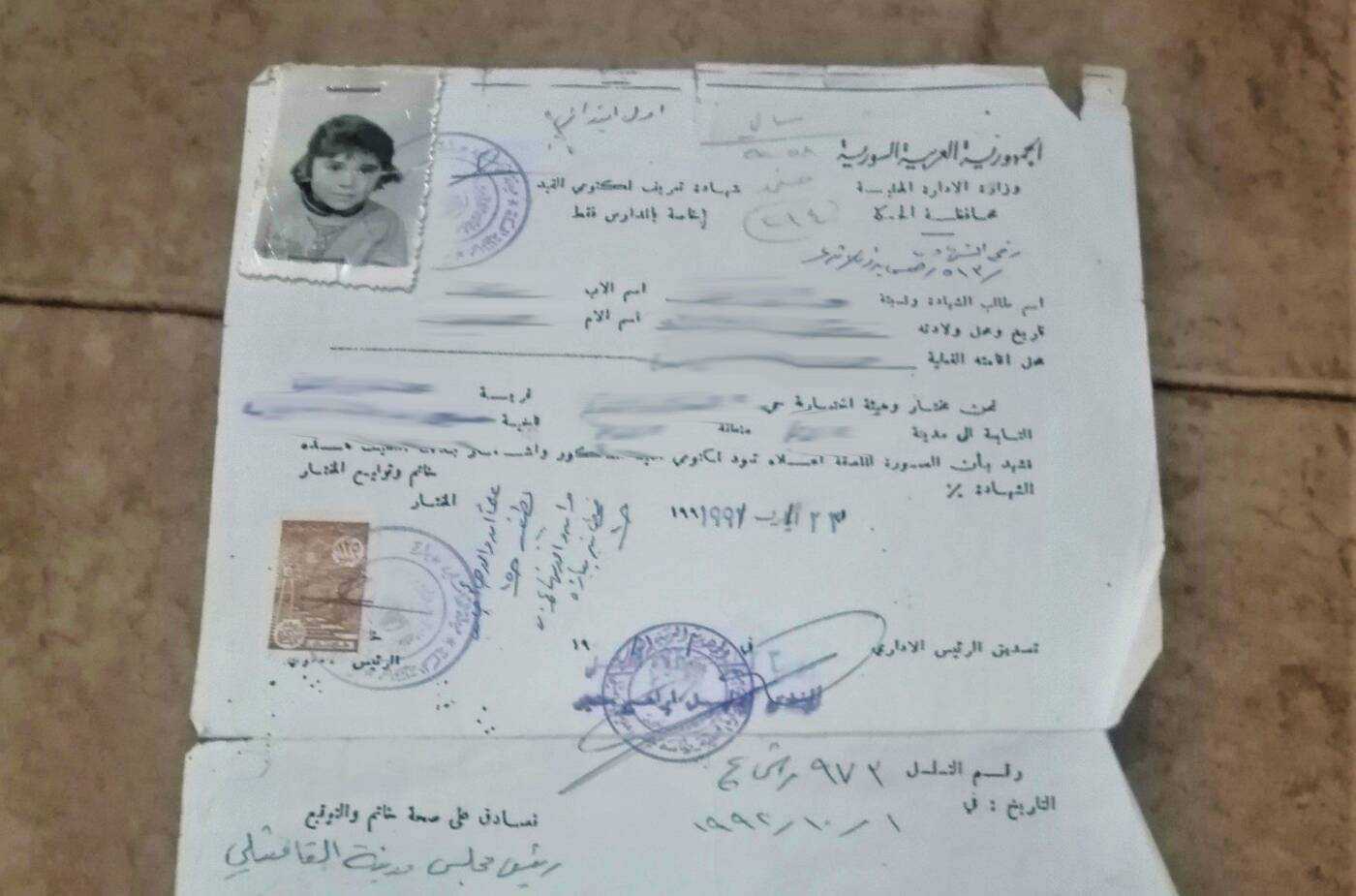

DOHUK — Sitting in a small living room carefully decorated in hues of gold and brown, Wane Musa Khalif carefully clings to a single sheet of paper. Delicately, she flattens the creased and worn document, slightly torn along the edges over the course of many years. Her younger self, a girl with short brown hair and a slight smile, looks out from a picture stapled to the upper left-hand corner. The paper, filled out in blue ink by a local tribal leader in her home province in Syria, was for many years Khalif’s only identification document and one of her most important belongings.

Khalif and her siblings were born stateless in Syria’s Hasakah province to Kurdish parents who lost their Syrian citizenship in 1962 during a sweeping government census carried out across the Kurdish-majority province. The official rationale for the census was that thousands of Kurds from Turkey had illegally emigrated to Syria in previous years. But this move also unfolded against a broader backdrop of government-led discrimination and demographic engineering policies aimed at Syria’s Kurdish minority.

Residents of the Kurdish-majority province were given a single day to provide identity papers proving that they had been living in Syria since before 1945. Those who could not were stripped of their Syrian nationality and property.

Around 33,000 Syrian refugees live in Domiz 1 refugee camp in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, including thousands of stateless Kurds, 5/9/2022 (Lyse Mauvais/Syria Direct)

The 1962 census deprived an estimated 120,000 Syrian Kurds of citizenship and associated basic rights: Stateless Kurds could no longer own property or businesses, travel, work in the public sector or earn university degrees. And as citizenship is hereditary in Syria, the population of stateless Kurds swelled to 300,000 by 2010.

“Throughout my childhood, we could not travel out of Syria, we could not study, most of us never went to university,” Khalif recalled. “Even if you completed your studies, it would be useless, no one would hire you.” When Khalif was diagnosed with cancer in 2007, her doctor advised her to seek care in neighboring Lebanon. But she could not travel abroad, so she stayed in Syria and had surgery in Damascus.

Khalif beat cancer and finally became a Syrian citizen in 2012, following Presidential Decree No. 49 of 2011, which allowed some stateless Kurds to apply for citizenship. Later displaced to neighboring Iraq by the war in Syria, Khalif now lives in Domiz 1—a camp on the outskirts of Dohuk in the autonomous Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI). Her four children are all Syrian citizens.

But statelessness is still a reality for many other residents of Domiz 1, which hosts around 33,000 Syrian refugees, most of them Kurds.

A recent assessment by the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) in KRI, where around 250,000 Syrians have sought refuge since the start of the war, estimates that one in 12 Syrian refugees in the Dohuk area are still stateless, 60 years after the 1962 census. Deprived of rights at home, statelessness followed them across the border, and thousands of Syrian Kurds face an uncertain future and unique obstacles as they work to rebuild their lives.

Second-class citizens

The 1962 census created two classifications of stateless Syrian Kurds: those who could not prove residency in Syria but had some types of identity documents became ajanib (“foreigners” in Arabic), while those who did not have any documents became maktoumeen (from the Arabic maktoum al-qaid, literally “concealed from the registry”).

Both groups experienced widespread discrimination from public institutions in Syria, and lost rights to property, education and healthcare reserved for citizens.

“We were second-class citizens in Syria,” Mustafa Ramadan Ali, a Syrian Kurd displaced to the Domiz 1 camp in 2019, told Syria Direct. “Everything was done to exclude us and dominate us. Even my grandfather, who had done his military service in the Syrian army, was not recognized as Syrian at the time of the census.”

Within the same family, it was common for various members to have different statuses, ranging from maktoum to full citizen. “Until 1986, I was a maktoum, but in high school my teachers told me I had to be at least ajnabi in order to finish my studies,” Muhammad Rashad Youssef al-Ali, a resident of Domiz 1, told Syria Direct. “My mother was maktoum like me but my stepmother was ajnabi, so by using connections to register as her son, I managed to become ajnabi and finish school.”

Maktoumeen men acutely felt the consequences of being stateless in their personal life. In Syria, only fathers can pass down citizenship, so Kurdish women who were citizens often refused to marry maktoumeen, fearing for their children’s future.

To overcome discrimination and recover basic rights, some stateless Kurds tried to use connections or bribe state officials. “It was difficult to become a citizen, but there was a slight possibility if you had any type of link with a Syrian citizen, any documents that could help and of course a strong link with a member of the regime,” Ramadan Ali said. “Some Kurds managed to get citizenship this way, because they knew someone.” In 1985, his grandfather, who had two wives—one of whom was a citizen—managed to recover citizenship for some of his children by paying huge bribes, he added.

An unresolved issue

The situation of stateless Kurds slightly improved in 2011, as nationwide protests erupted against the regime of Bashar al-Assad. Shaken by the fall of other authoritarian leaders in the region, Assad extended a hand to the very Kurdish minority his regime had historically repressed, seeking to appease them and limit the spread of revolution to Kurdish-majority regions.

Presidential Decree No. 49 of 2011 allowed all ajanib to apply for citizenship, and proved hugely popular. Syria’s ajanib population plummeted by 93 percent, from more than 300,000 in 2011 to less than 20,000 in 2018, according to the human rights monitor Syrians for Truth and Justice.

Still, many were excluded from the decision. Maktoumeen (around 150,000 people in 2011) were simply not mentioned in the decree, while some ajanib who could have applied did not because they did not know how, or distrusted authorities when the measure was first announced as repression of regime opponents raged on.

“This isn’t an issue that is gone and has been resolved, it’s still an issue affecting a considerable number of people,” Thomas McGee, a PhD candidate at the Melbourne Law School’s Peter McMullin Center on Statelessness working on the post-2011 evolution of statelessness in Syria, told Syria Direct. “The way [Decree 49] is interpreted [by many European lawmakers] is that there are no longer any stateless Syrian Kurds, and that the issue is solved,” he added. “This leads to issues of non-credibility for anyone claiming to be a stateless Kurd from Syria, now arriving in Europe.”

In fact, many stateless Kurds fled Syria before they could claim their rights, and ended up in exile without any official documents. A recent NRC survey of Syrian refugees in Dohuk found that 7,000 out of 86,000 Syrian Kurds in the region may still be stateless, or eight percent of the Syrian refugee population.

The same assessment found that one of the main obstacles to citizenship is the fear of returning to Syria: 14 percent of those affected felt they could not safely return to initiate the citizenship process, and another 14 percent did not know how to apply.

To recover citizenship, those who are eligible must travel to Syria—a daunting prospect for many who fear detention by the Syrian regime or the Kurdish-led Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES) if they have not completed their military obligations, for example. Those who are politically active may also be wary of returning due to persisting political tensions between Kurdish parties within northeastern Syria, which is politically dominated by the Democratic Union Party (PYD). Many of the Kurds who sought refuge in Iraq support the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), the ruling party in Iraqi Kurdistan, and its Syrian affiliate.

Other stateless Kurds balk at the cost of the trip, and the various fees and bribes they may need to pay. “My uncle went back to Syria three months ago and paid the equivalent of $2,000 to a lawyer, in order to be recorded as a citizen along with his wife,” Ramadan Ali said. “And he has eight children for whom he still needs to do the paperwork.”

A shop in the Domiz 1 refugee camp for Syrians in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq advertises German language classes. Emigration to Europe is a dream for many Syrian Kurds, 5/9/2022 (Lyse Mauvais/Syria Direct)

Eyes on Europe

Kurdish authorities in northeastern Syria and the Kurdistan Region of Iraq do not differentiate between stateless and citizen Kurds. Both are eligible for locally issued identification documents.

In fact, “for most of these [stateless] families, the KRI residency is the first form of legal identification that they have ever had,” Caroline Zullo, Policy and Advocacy Advisor at NRC Iraq and co-author of the organization’s August report on stateless refugees, told Syria Direct.

Now a schoolteacher in the Domiz 1 camp, al-Ali (who was almost prevented from finishing school because he was maktoum) says he does not know how many maktoumeen and ajanib students attend his classes, because their status is simply not recorded. “Any child who has residency in Iraqi Kurdistan can be registered,” he said.

But problems arise when Kurdish refugees try to leave Iraq, where many feel considered as “forever guests.” “There is no future for us in Iraq: We will never become citizens, we will never own houses and land,” Ramadan Ali said. Although KRI can issue residency permits that are valid in Kurdish areas, granting Iraqi nationality remains the prerogative of the central government in Baghdad, which likely has no intention of nationalizing tens of thousands of additional Kurds.

As a result, many Syrian Kurds believe they need to reach a third country to seek a stable future, but statelessness exposes some to additional challenges.

“There is a huge information gap about stateless Syrian Kurds, what documents they are supposed to have,” Zullo said. “There have been issues, in terms of applying for resettlement, or seeking asylum in third countries, because most authorities assume they should have applied for citizenship after the 2011 decree. In some ways, [this confusion] could foster more informal pathways of migration and displacement, if there is no formal pathway to take,” she said.

In practice, asylum authorities struggle to recognize the identification documents issued by local authorities for stateless Kurds—often a simple sheet of paper with a photograph— because they cannot authenticate them, and the documents seem easy to forge.

“Stateless Kurds also face specific challenges when it comes to family reunification,” McGee said. “It starts with the fact that to initiate family reunification, the family member in Europe has to demonstrate they are related. But again, how do you prove something when your only documents are not considered as credible?”

Some families have been asked to undergo DNA testing, but recognized centers are not always available where they live. Often, they have to present themselves to an embassy, in the best case in Erbil or Baghdad, which can be challenging since KRI residency is not valid in the rest of Iraq. Other asylum seekers have to go all the way to Beirut, Amman or Cairo, all without proper travel documents. “Some might consider smuggling themselves in through Turkey,” McGee said. “I know of cases that have gone back to Syria in order to get to the border with Lebanon.”

‘We already lost our rights’

When Decree No. 49 was issued in 2011, al-Ali was among the thousands of stateless Kurds who rushed to become a citizen. He hoped to be able to work in the public sector as a teacher, something he could not do as an ajnabi. But this time it was the advancing war that stood in his way. “I didn’t get a single benefit from becoming a citizen,” al-Ali said regretfully. “We left Syria in 2013 and I didn’t even have time to register our house under my name.”

Likewise, by the time Khalif became a citizen in 2012, the damage was already done. “We had already lost our rights, we lost the opportunity to get an education, so becoming citizens didn’t change much for our situation,” she said.

An overwhelming 94 percent of stateless Kurds interviewed by NRC in August said they do not intend to return to Syria. But even in exile, citizenship is the only path to a more stable future. “What if tomorrow international organizations or Iraqi authorities tell us to go back to Syria, and we are forced to return? We need to ensure that if we go back, we will have some rights there,” Mustafa Ramadan Ali’s wife Hiyam told Syria Direct.

“We need help from international organizations for those wishing to recover their rights and become citizens,” Ramadan Ali added. “We need people to help us with legal procedures in Syria so that we no longer have to give our savings to lawyers. In reality, many people want to return to their land, because in Syria we are not foreigners.

But that will only be possible if we get our full political rights.”