Three Syrian survivors counter Greek authorities’ Pylos shipwreck narrative: ‘They tied a rope, we capsized, they sailed away’

Around 150 Syrians were among the estimated 750 people on board the vessel that capsized near Pylos last Wednesday. Only 104 people survived, including between 30 and 40 Syrians. Survivors held Greek coast guards responsible for the shipwreck and delayed rescue efforts.

19 June 2023

MALAKASA — Four days after surviving one of the deadliest migrant shipwrecks in recent memory, three Syrians countered Greek authorities’ narrative of how a fishing vessel carrying 750 people capsized and sank off the coast of Pylos on June 14.

Only 104 people survived the boat’s sinking, while 80 bodies have been recovered. More than 550 people are estimated to remain missing in the Calypso Deep, the deepest of the Mediterranean Sea.

On Saturday morning, 71 out of the 104 survivors were at the Malakasa reception center north of Athens. Camp authorities and police repeatedly tried to prevent Syria Direct’s reporter from speaking with survivors through its barbed wire fence, and barred survivors from exiting the camp to speak with members of the press gathered outside.

“The Greek boat tied a rope in the middle of the boat. It went right, left and then right again, very quickly. Then the boat capsized, and everyone fell into the water,” one young Syrian in his twenties said, requesting anonymity. “Then, they [the Greek coast guard] sailed away and watched us from afar. We spent about two hours in the water,” he added. Two other Syrian survivors gave the same account. “They came to rescue later with smaller boats,” he added.

These testimonies differ from the Hellenic Coast Guard’s narrative of the wreck. A Greek government spokesperson said on Friday that the coast guard tied a rope to the overcrowded boat three hours before it capsized, and that the intention was not to tow the vessel but to approach and see if they wanted help.

Greek authorities have been in the spotlight before for pushbacks, towing migrant vessels out of their territorial waters. According to the monitoring group Aegean Boat Report, between 2017 and 2022, 48,983 people were pushed back from Greek islands into Turkish waters.

Greek authorities also said that the boat had been on a “steady course and speed” and did not request help before it sank. However, a BBC investigation tracking data of the boats around the migrant vessel has revealed that it barely moved for seven hours before it capsized.

“It is vital that there will be a full and credible investigation and that might require international involvement,” Judith Sunderland, Associate Director of the Europe and Central Asia Division at Human Rights Watch, said. “Hundreds of people have died, so it has to be a criminal investigation leading to accountability, not only the truth about what happened but also full accountability for those responsible up the chain of command,” Sunderland added.

The UNHCR Special Envoy for the Western and Central Mediterranean, Vincent Cochetel, has also called for an independent investigation. “Some testimonies suggest that at that time there was a maneuver by the coastguards to take it away from the search and rescue area from Greece,” he told CNN last week.

Greek authorities have said there is no footage of the rescue because images from the coast guard vessel’s camera were not recorded. But while the full story of what happened from the first alert about the migrant boat on Tuesday until it sank in the early hours of Wednesday remains unclear, a rough timeline has emerged:

The Hellenic Coast Guard said its forces at the scene did not act before the boat capsized because the people on board refused assistance. Sunderland said that argument was “legally and morally” unacceptable. “The boat was in distress, it was unseaworthy, overcrowded and they had already launched distress calls to Alarm Phone. It is a paramount obligation of all vessels in the area, and certainly a coast guard, to provide immediate assistance,” she added.

Even if some people on the boat refused the coast guard’s assistance, that “does not absolve the Hellenic Coast Guard of their responsibility to immediately secure the boat and the lives of the people on board,” Sunderland added.

The European Council on Refugees and Exiles has documented Greece’s systematic lack of response to alerts of people in distress and pushbacks by land and sea. In May, the New York Times published footage of Greek authorities taking asylum seekers to the country’s coast and abandoning them on a raft, a practice that was also documented by Der Spiegel in October 2022.

“Given the history of misconduct by the Greek coast guard and its documented involvement in pushbacks, we certainly have reason to question their version of events,” Sunderland said.

“It is a responsibility and duty for the Greek government to give us transparent and clear answers, which is not happening for the moment,” Efi Latsoudi from the Greek NGO Refugee Support Aegean (RSA) said. “We don’t have a clear picture.

Malakasa ‘like a prison’

The Malakasa Reception and Identification Center north of Athens, where 71 survivors of the June 14 Pylos shipwreck were staying on Saturday, 17/6/2023 (Alicia Medina/Syria Direct)

Friends and relatives of the missing gathered at the door of the Malakasa Reception and Identification Center on Saturday morning. On the other side of the barbed wire fence, a handful of survivors stared at the photos on phones passed to them by family members frantically asking: “Is he alive?”

Five Syrian survivors at Malakasa told Syria Direct they believed around 150 Syrians were on the boat, most of them from the country’s southern Daraa province, but also from Homs, Aleppo, Damascus and Suwayda. Only around 30 or 40 survived.

According to AFP, there were 35 Syrians from the northern Aleppo city of Kobani onboard. A local media group in Daraa said 112 people from the province were also on the ship, 35 of whom survived, while 22 were among the recovered bodies and 55 are still missing.

All the 71 survivors at Malakasa are men, a spokesperson of the Greek Ministry of Migration told Syria Direct on Saturday. Five survivors who were minors were taken to other camps, while three minors remained hospitalized. Nine Egyptian nationals who also survived the wreck were detained by Greek authorities on Thursday night and accused of human trafficking.

Muhammad Sablah, a 24-year-old from Aleppo, is one of the survivors at Malakasa. Before boarding the ship, he had fled from Syria to Lebanon and on to Libya in the hopes of reuniting with his brother and sister in Germany. He did not want to talk about the sinking on Saturday. “I just want to leave this center and go to Germany,” he said. “They are telling us we can’t leave. This feels like a prison!” A camp worker told him to get away from the fence, and the interview ended.

Sablah said he only personally saw four women and three children on the boat, but that there were many unaccompanied teenagers. Amjad, a 27-year-old from Homs, confirmed these figures and said the boat was carrying “Egyptians, Syrians and Pakistanis.” Through the Malakasa fence, Amjad complained about the lack of phones to communicate with their relatives.

Another Syrian survivor, who asked not to be named, also complained about the lack of phones. Still, “we were able to contact our families through the phones of the other migrants here in the camp, via Facebook,” he said.

Migration authorities told Syria Direct on Saturday they would provide SIM cards to survivors the following day. Syrian survivors confirmed the center had doctors and psychologists. Since Sunday, “survivors have been contacted by lawyers and legal organizations,” Efi Latsoudi from RSA said.

Latsoudi explained Malaksa is a “closed controlled center,” meaning that camp authorities can control the movement of the people inside the camp, who can be in the center for up to 25 days until their asylum claim is processed.

“These people shouldn’t be detained, and shouldn’t be in the conditions of the camp because they are victims of a tragedy. They should be supported in humane conditions and according to their needs,” Latsoudi said, adding that survivors should have been provided access to phones quickly in order to inform their relatives and “not be treated as prisoners and deprived of talking about what happened.”

On Monday, six days after the boat disaster, Greek authorities still had not made a definitive list of survivors publicly available, while the Egyptian embassy had already shared the names of the 43 Egyptian survivors.

More than 100 Syrian families are still waiting for news of their loved ones.

‘Is he alive or dead? We want to know’

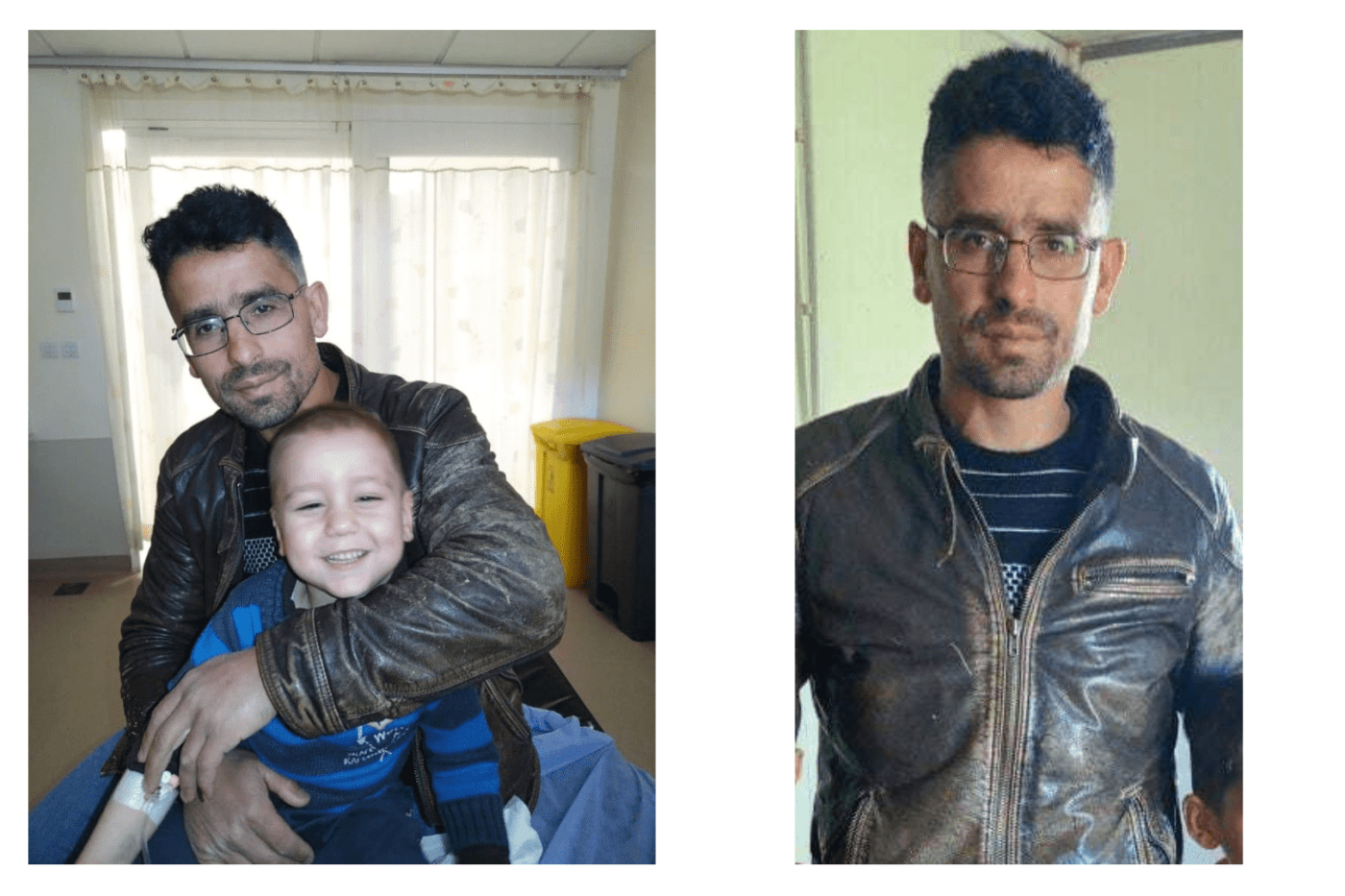

Thaer al-Rahhal, 39, is among hundreds of people missing following the June 14 Pylos shipwreck. Al-Rahhal, originally from Daraa province, lived in Jordan’s Zaatari refugee camp and made the risky journey to Europe in the hopes of finding work to pay for his four-year-old son Khaled’s leukemia treatment. (Photos courtesy of the family)

Nermin Hassan al-Zamal and her husband Thaer al-Rahhal had navigated life as well as they could at Jordan’s Zaatari refugee camp since fleeing Daraa in 2013. But one year ago, their four-year-old son Khaled was diagnosed with leukemia.

At first, Khaled received treatment at the King Hussein Cancer Center in Amman. Then, “it stopped my son’s treatment due to the lack of financial coverage,” al-Zamal explained. The Syrian mother said UNHCR told the family it could not cover the medical treatment. “They returned him to the camp, they stopped his treatment on July 4 of 2022,” she said.

Due to the “downward funding we’re witnessing in recent years, unfortunately, a number of partners have been forced to limit some of their services, or even worse, shut down some operations,” Meshal Elfayez, a Communications Officer at UNHCR Jordan, said. “More funding is needed to achieve solutions for the refugee response.”

After UNHCR informed the family they could not cover the medical costs, Khaled’s treatment at King Hussein Cancer Center was “continuously interrupted” due to lack of funds from private donors. Al-Zamal said the center informed her they could not cover the cost of a bone marrow transplant Khaled needed.

Thaer believed the only way to cover the medical costs was to try to reach Europe. His friends in Germany gathered money to pay the smuggler and two months ago, the 39-year-old flew to Alexandria and then traveled to Libya.

On Thursday, June 8 at 6:30pm, al-Rahhal called his wife from Tobruk. “He told me: ‘There are a lot of people on the boat, I don’t know if the smuggler will let me in, but I will prepare myself just in case,’” she said.

That was his last call.

“His only reason to get on that boat was to pay for our son’s treatment,” al-Zamal said.

June 8 was also the last time the al-Dnifat family heard the voice of 17-year old Sufyan. The Syrian teenager fled Daraa for Libya last year to avoid conscription in the Syrian army. “Life in Syria is unbearable, there’s no work and no stability and people live in fear,” his uncle Muhammad al-Dnifat told Syria Direct from Jordan.

Sufyan al-Dnifat, 17, from Daraa province is one of the hundreds of people missing following the June 14 Pylos shipwreck. He left Syria in 2022 to avoid conscription into the regime’s army. (Photos courtesy of the family)

“He told me they might travel on Friday. He was scared, but he didn’t know the condition of the boat or that it would be that many people,” al-Dnifat said. “Until now, we have no news about his fate. Where is he? Is he alive or dead? We want to know.”

“He just wanted to go and live a normal life like any other human, his goal was to leave for a better life,” his uncle said.

A cemetery in the Mediterranean

Rescue operations continued on Sunday, five days after the wreck. With 80 confirmed deaths and more than 550 people estimated missing, the Pylos shipwreck is one of the deadliest migration tragedies in the Mediterranean since April 2015, when 1,072 people perished as an overcrowding fishing boat sank off the coast of Libya.

The Mediterranean Sea is the deadliest migration route in the world. “Year after year, it continues to be the most dangerous migration route in the world, with the highest fatality rate,” Federico Soda, International Organization of Migration (IOM) Director for the Department of Emergencies, said. “States need to come together and address the gaps in proactive search and rescue, quick disembarkation, and safe regular pathways,” he added.

The fatality rate in this migration route can be explained—among many factors—by the European Union's attempts to reduce the number of arrivals at its shores. The European Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex) “and the European Union as a whole have pulled back vessels from the Mediterranean that could be used to do search and rescue, and have instead implemented Frontex aerial surveillance of the Mediterranean,” Sunderland said. She also pointed to obstruction and harassment of NGO rescue boats.

Sunderland also criticized Frontex’s “flawed and dangerous” definition of “distress at sea,” an approach that doesn’t comply “with the consensus definition of distress even in EU regulations.” She explained that is a standard practice for Frontex to only alert coastal authorities, not all vessels or NGO rescue ships, unless there is an “absolute imminent risk of loss of life.”

The head of Frontex resigned in April 2022 after an anti-fraud investigation and reports by investigative media organization Lighthouse Reports documenting human rights violations and pushbacks.

On June 8, the same day Thaer al-Rahhal and Sufyan al-Dnifat embarked from Libya with hundreds of others on their ill-fated journey to Italy, the EU reached a new agreement on asylum and migration management.

Human Rights Watch warned the deal would lead to more abuse at Europe’s borders for asylum seekers who entered irregularly or were rescued at sea, due to “sub-standard accelerated procedures with fewer safeguards, such as legal aid” where people will likely “be locked up during the procedure, which could take up to six months.”

Sunderland criticized EU leaders for “deputizing countries like Libya to do their dirty work to try to prevent boats from reaching Europe.” Under a Memorandum of Understanding with Italy signed in 2017, Italy helps the Libyan Coast Guard stop migrant boats and return their passengers to detention centers in Libya, where many face extortion and abuse.

Speaking from Libya’s coastal city of Tobruk, 22-year old Syrian Ameen al-Tibawi told Syria Direct two of his friends were on the vessel that sank in Pylos: 22-year-old Mahmoud Khaled al-Saidi and 23-year-old Muhammad Firas Mahameed. “They were in Jordan and left for Libya 10 months ago. They were jailed and faced a lot of hardships in Libya. They didn’t know how to swim,” al-Tibawi said.

Their goal was to reach Italy and then go to Germany. “One of the survivors told us that the Greek coast guard sank the boat,” al-Tibawi said.

Despite losing two friends on the shipwreck, al-Tibawi, who left Daraa in February, is waiting for his chance to make the crossing.

“I will try to embark on the next boat.”

Family members of those missing in the Pylos shipwreck can contact the Red Cross hotline by phone at 00302105230043, 00302105140440 (interpretation available) or by email at tracingstaff@redcross.gr. The Greek Ministry of Immigration and Asylum’s Hellenic Disaster Victims Identification Team can be reached at 00302131386000 and dvi@astynomia.gr.

This story has been updated with further medical details of Khaled's case.