Turkish-backed opposition shelling keeps ‘a people of olives’ from their land in Afrin

When Turkish-backed opposition forces took control of most of Afrin in 2018, villages on its outskirts became a line of contact with regime forces. There, residents face repeated shelling and cannot access their farmland, once their main livelihood.

23 June 2023

AFRIN — Ahmad Majid, 70, stands a few hundred meters from his land in the Sherawa subdistrict of Afrin, in the northern Aleppo countryside. From here, he can see the olive trees whose fruit he has not been able to harvest for the past five years. In that time, some of his trees were consumed by fire as he watched from a distance, unable to put it out.

Majid lives in Sughana, a village controlled by the Syrian regime south of Afrin city. Five years ago, his village—and the agricultural land surrounding it—became a line of contact with Turkish-backed opposition Syrian National Army (SNA) factions stationed in the Afrin area.

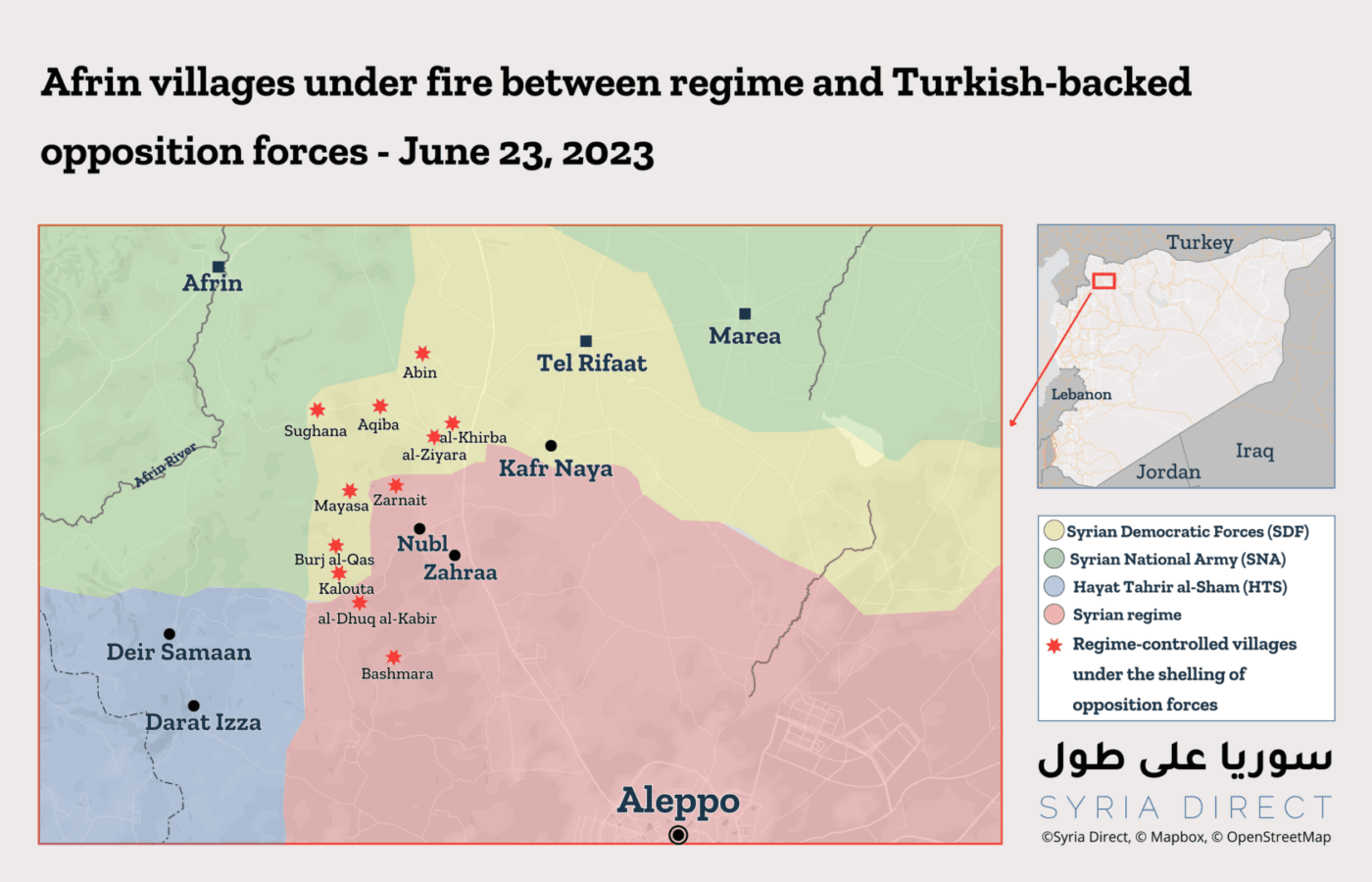

On January 20, 2018, Turkey and the SNA launched Operation Olive Branch, a cross-border military operation against the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG) in the Afrin area of Aleppo. Opposition forces took control of Afrin, with the exception of several villages located in the Sherawa subdistrict: Sughana (also known as al-Basliya), Aqiba, al-Ziyara, al-Khirba, Burj al-Qas, Abin, Kalouta, Bashmara, Zarnait, Mayasa and al-Dhuq al-Kabir. Regime forces entered the villages in March 2018 after Kurdish forces withdrew.

The Sherawa villages are now militarily controlled by Damascus, while they lie within territory controlled by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), of which the YPG are a main component.

Afrin villages under fire between regime and Turkish-backed opposition forces – June 23, 2023 (Syria Direct)

The villages form a dividing line between areas of Turkish influence in Afrin and the Shiite-majority towns of Nubl and Zahraa in Aleppo countryside, both of which are controlled by the regime and Iranian militias affiliated with it. People here believe there is an undeclared Syrian-Turkish agreement making their villages a buffer to protect Nubl and Zahraa from opposition attacks, local civilian sources told Syria Direct.

Operation Olive Branch blocked the main road leading to Sughana village, Majid’s hometown. Before, the route was lively and crowded, a link between the cities of Aleppo and Afrin. It is the same road former Lebanese President Michel Aoun traveled in 2010, when he visited the tomb of St. Maron in the ancient village of Brad.

Today, Sherawa’s villages are hit from time to time by shells originating in areas controlled by opposition factions and Turkey. The attacks have killed and injured civilians, destroyed many homes and burned agricultural lands that are a main source of livelihood for their owners.

Sughana, a village in the regime-controlled portion of the Afrin countryside. In the distance lies farmland that is a line of contact with Turkish and Turkish-backed opposition forces, 16/4/2023 (Sozdar Muhammad/Syria Direct)

In mid-April, several shells landed on Sughana and Majid spent “a terrifying night in a cave near the house” with his family. The shelling “damaged some houses, and many residents temporarily left their homes,” he said.

As he spoke, Majid gestured with his hand to the neighboring village of Kimar, which is controlled by the Ankara-backed opposition. “The shells came from there. Thank God nobody was hurt,” he said. “This has been our situation for more than five years.”

In Aqiba, two kilometers from Sughana, Ahmad Ali Manla’s father was killed and his sister was injured during opposition shelling in February 2020, the 43-year-old told Syria Direct.

Five years of shelling have pushed many families in the area to leave their homes. Some left for regime areas: Aleppo city or camps in villages in the al-Shahbaa area of the northern Aleppo countryside. Others traveled to SDF-controlled northeastern Syria.

In Sughana, only 20 families are left out of 150 families who inhabited it before 2018, people from the village estimated. Those who remain are clinging to their homes, trying to cope with the current conditions. For Majid’s family, “shelling has become commonplace,” he said.

Fallow land

After the villages became a line of contact with Ankara-backed factions five years ago, some property owners tried to access their nearby land to plow it and harvest olives, but were shot at, multiple local families told Syria Direct.

Since then, farmers have not been able to cultivate or till their land, which lies fallow. According to the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA), fallow land is “cultivated land that is not seeded for one or more growing seasons. The maximum idle period is usually less than five years.”

Majid owns two hectares of land in Sughana, upon which he once grew wheat, barley and lentils. He also had 400 olive trees and a number of fig trees and grape vines, which he planted with his father more than 5o years ago. “The land was our family’s sole livelihood for four decades,” he said.

Many of his olive trees, wheat, barley and lentil crops were burned during Operation Olive Branch, and “opposition factions stole 40 sheep that were grazing near the village,” Majid said.

His wife, Zulikh Maamu, interjected, saying: “He cried for his sheep for several days, after we received word that opposition forces in Kimar slaughtered them to eat them.”

In Aqiba, Manla is in a similar situation. He owns 200 olive trees, fig trees and grape vines in an area near Basla village, which is controlled by the Turkish-backed opposition. He cannot access them “for fear of being shot,” he said.

Manla’s land used to produce between 20 and 30 16-liter tanks of olive oil each year. But today, he uses vegetable oil to prepare food, making do with buying “small bottles of olive oil,” he said.

Agriculture and livestock rearing are among the most important sources of income in these Afrin villages. As years of shelling has prevented residents from accessing their land, the economic situation of those who remain in the area has deteriorated. Local families rely on monthly food aid provided by the Syrian Arab Red Crescent (SARC), consisting mainly of rice, bulgur and lentils. As for fruits, vegetables and meat, “most of us can’t buy them,” Majid said.

Abud Bakri Abdo, 51, and his three brothers live in the regime-controlled village of al-Dhuq al-Kabir, but their 15 hectares of land lie near the opposition-held village of Kabshin. They have not been able to access or cultivate their land since 2018.

That year, Abdo and his brothers had planted their land with wheat, barley and lentils. “We weren’t able to harvest that season,” he said, accusing Turkish-backed factions of “setting fire to our crops.”

From each of their homes, Majid, Manla and Abdo can look out on neighboring villages in Turkey’s area of influence. They can see opposition military points, and sometimes hear the sounds of nearby mosques. Occasionally, they can hear the voices of vendors shouting in the distance. Their land lies in the space between: a dividing line, unreachable.

“We are a people of olives, who now prepare our food with vegetable oil,” Majid said in a voice choked with emotion. “They shoot at us, as if saying: This is not your land.”

In the hope of one day returning to his land, Manla is determined to remain in his village. “A day will come when we will plant our land again, and care for its trees,” he said.

**

This report was produced as part of Syria Direct’s MIRAS Training Program for early-career journalists in northeastern Syria. It was originally published in Arabic and translated into English by Mateo Nelson.