Under the axe: The fall of Daraa’s forests and fruit trees

Trees have fallen under the axe in Daraa and across Syria since the spring 2011 revolution, cut for wood to sell or use as an alternative to heating and cooking gas during war, siege and economic crises. Since 2020, however, logging has increased to include fruit-bearing trees on private farmland and within cities.

12 March 2024

PARIS — Abu Qassem had a choice to make. He could either see his son drafted into the Syrian army, or sacrifice his olive trees—an inheritance from his own father—to fund a way out.

To “save his life and secure his future,” the 50-something farmer cut down his 27-year-old olive trees, a grove of 1,000 on his land in Inkhil, a town in the north of Syria’s southern Daraa province. Abu Qassem sold the felled trees to a firewood dealer for $21,000, and spent $19,000 of it to get a passport for his son, secure a visa to the United Arab Emirates and start a business for him there.

Abu Qassem grieves the trees he spent 15 years tending. They were “my life companions,” he said. “I cared for them every day. They supported us, and were enough for the whole year.” But if his son remained in Inkhil, “he would stay hidden, for fear of being drafted into military service, or be taken away without us knowing if he would return or survive.”

Trees have fallen under the axe in Daraa and across Syria since the spring 2011 revolution, cut for wood to sell or use as an alternative to heating and cooking gas during war, siege and economic crises. Since 2020, however, logging has increased to include fruit-bearing trees on private farmland and within cities.

Over the past three years, an unprecedented fuel crisis in regime-held parts of Syria has driven increased logging. As people increasingly rely on firewood, demand increases and its price goes up. Farmers, who cannot care for their trees properly due to water shortages and the high cost of fertilizers and pesticides, face difficult choices.

In Daraa, one ton of firewood currently sells for around SYP 3.4 million ($237.75 according to the current black market exchange rate of SYP 14,300 to the dollar), one firewood seller in the province’s eastern countryside told Syria Direct.

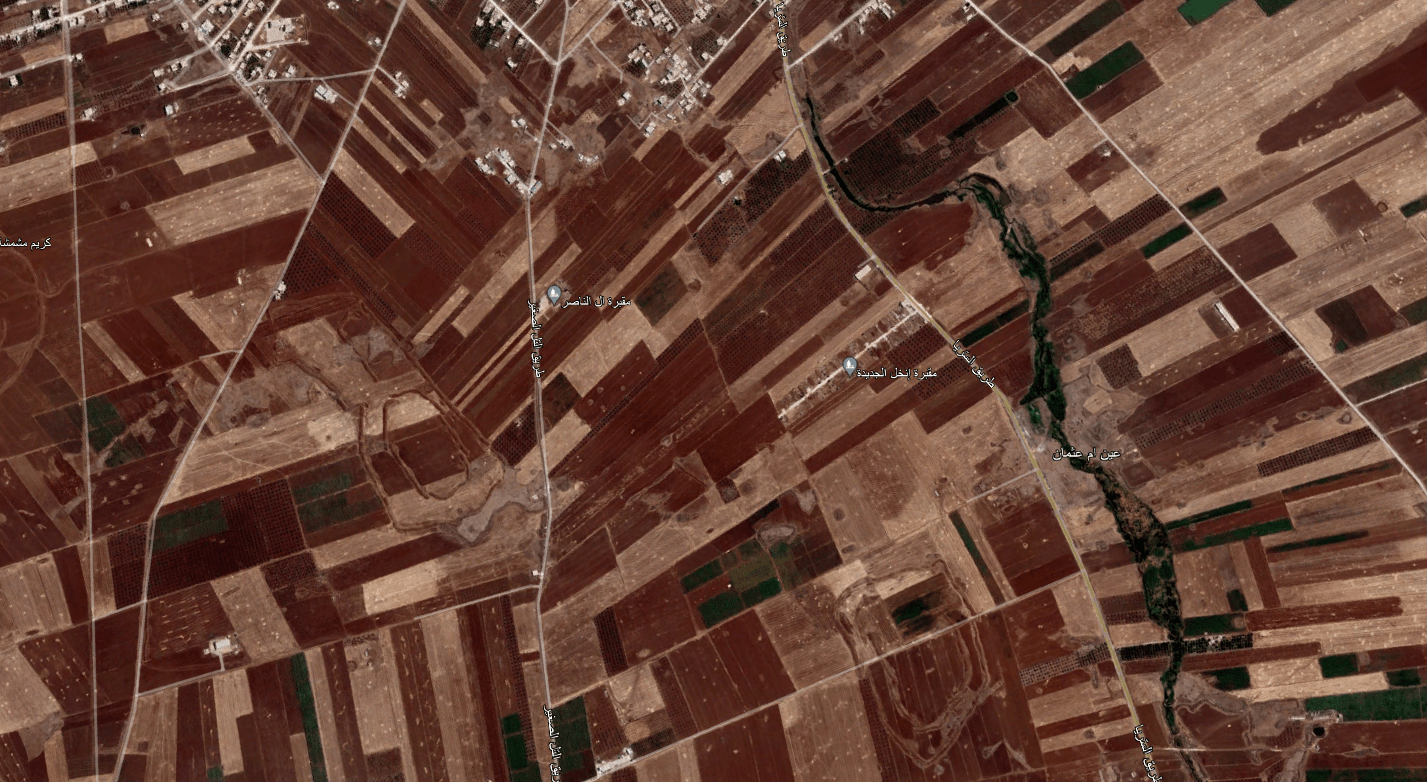

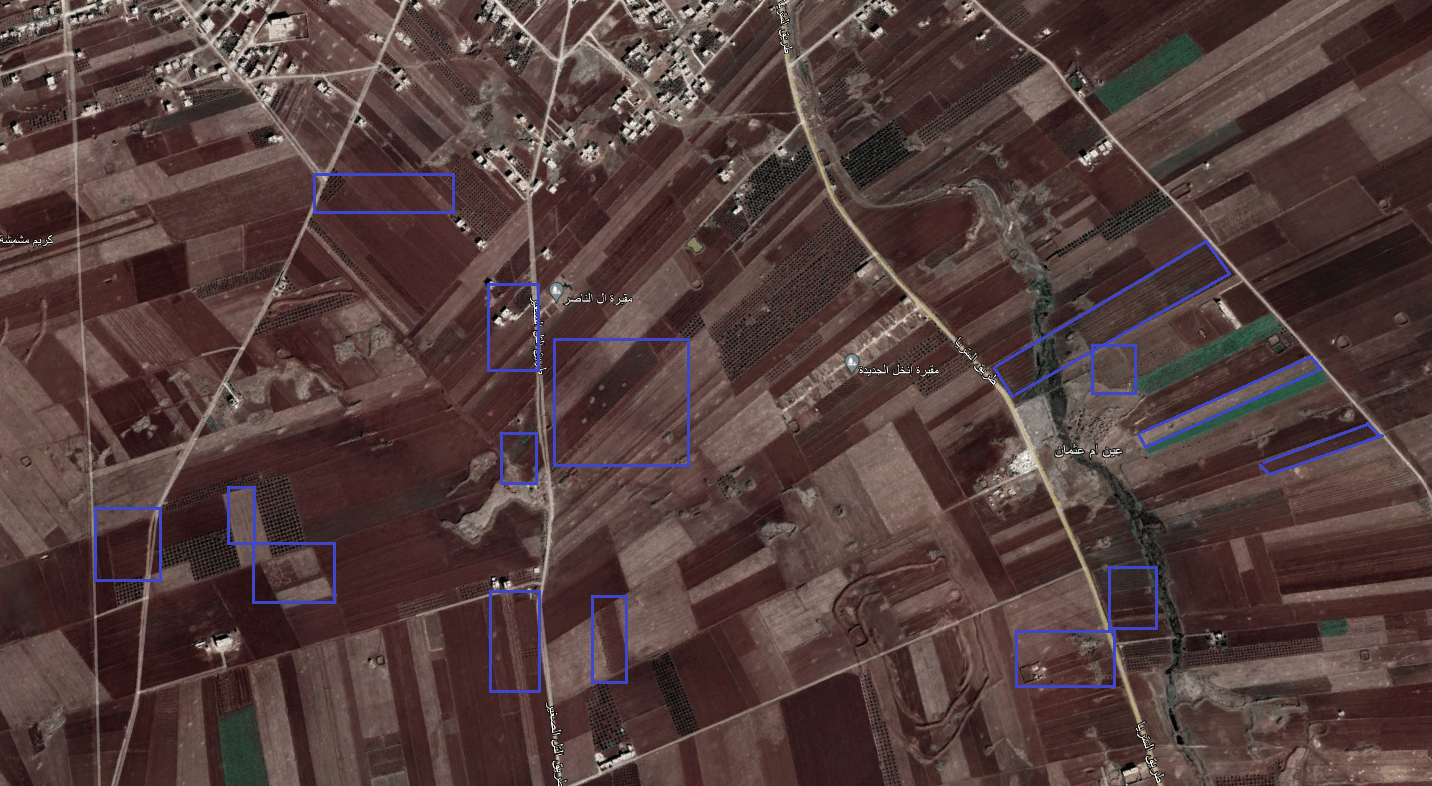

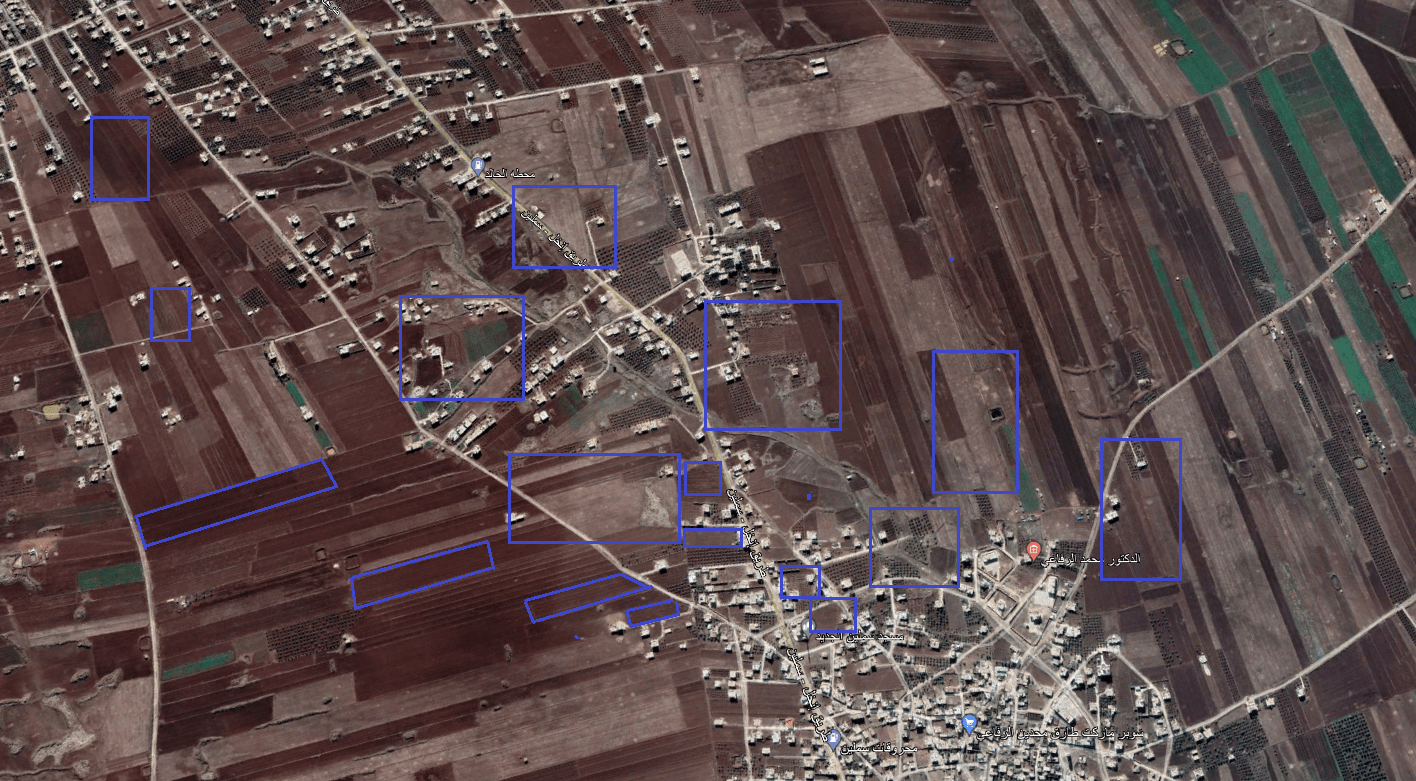

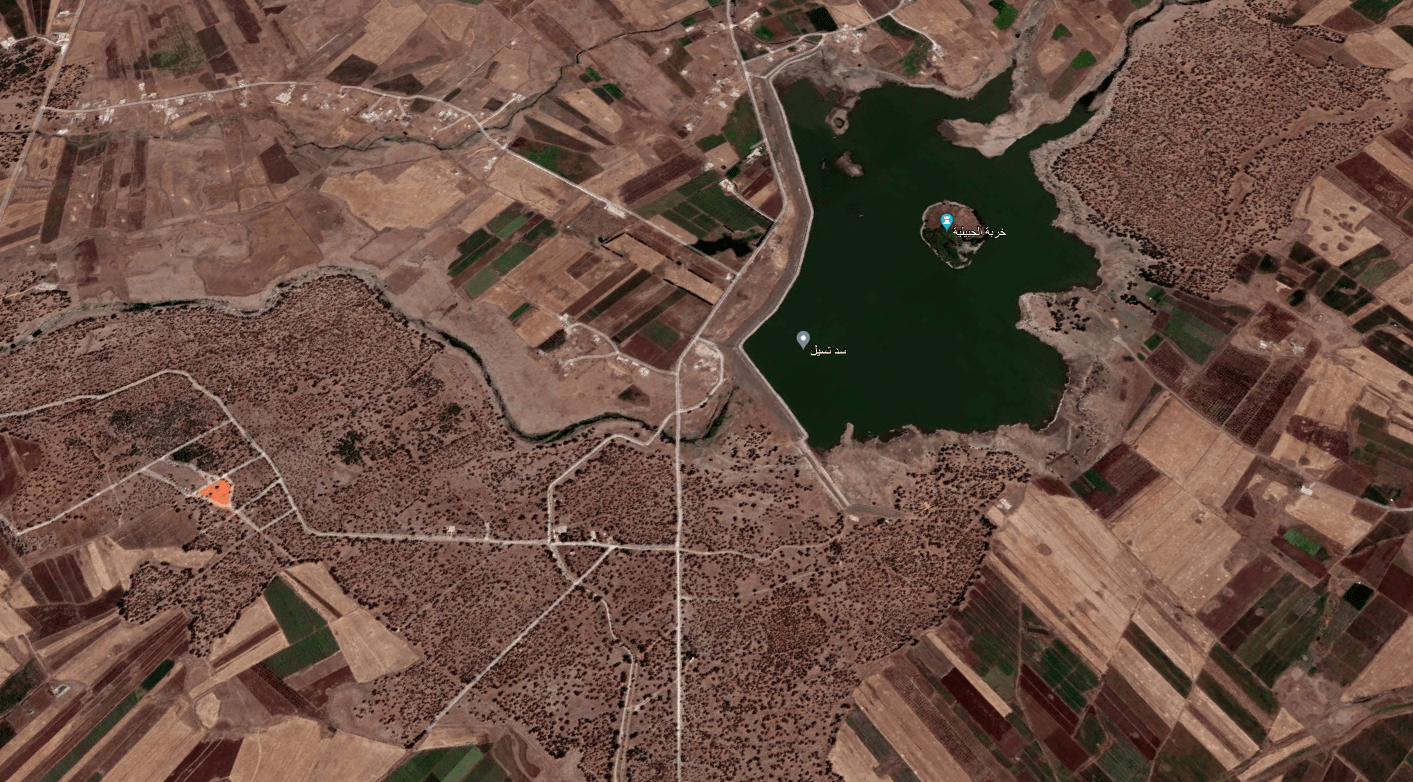

Satellite images of a northern neighborhood in the Daraa town of Inkhil show areas planted with fruit-bearing trees, such as olives, cleared between August 2011 (left) and December 2022 (right). (Google Earth/Syria Direct)

Felling fruit trees

Over the past few years, the productivity of Abu Hussam’s olive trees on his land in the northern Daraa city of Jassim fell due to “insufficient rainfall, and my inability to water them,” he said. Their yield no longer makes up for “the cost of caring for them—plowing, pesticides and fertilizers,” the farmer told Syria Direct. Some of his trees “produce less than four kilograms of olives, which doesn’t cover the costs.”

Meanwhile, Abu Hussam has struggled with “the fuel crisis, and our urgent need for firewood for heating and cooking, especially in the winter months.” As a result, he has cut down his trees in batches, most recently “uprooting 10 trees two months ago.” He planted his 120 trees in 2005.

Similarly, Abu Muhammad, 45, cut down his 250 olive trees in Inkhil in 2021. They were in poor condition, and he gave up hope of restoring them. He had left his grove in the care of his brother in 2013, when he fled south to neighboring Jordan with his family, like hundreds of thousands of Syrians.

In 2021, Abu Muhammad returned to his hometown, only to find his land “in a deplorable state,” he said. He consulted with an agricultural engineer, who “said my trees needed special care for three years, during which the land had to be plowed and fertilized, and the trees pruned and watered. I had no ability to do that, so I decided to cut them down,” he added. “Uprooting the trees was a tragedy for me, because I spent 20 years caring for them.”

After uprooting fruit trees such as olives or pomegranates, farmers replace them with seasonal crops that are less expensive and faster to produce, including wheat, barley and legumes. After cutting down his 1,000 trees to pay for his son’s travel, Abu Qassem planted his land this year with wheat and beans, hoping for a “good season.” Abu Hussam also plans to plant wheat.

The success of Abu Qassem’s crops depends on the availability of fuel, fertilizers and pesticides, as well as the level of rainfall in the southern province. For several years, Daraa’s wheat farmers have been hit hard by a fluctuating climate, in an area once so productive it was historically called the “granary of Rome.”

Read more: ‘Granary of Rome’: Can the Houran’s wheat survive climate change and war?

In Inkhil, around 80 percent of farmers have uprooted their fruit trees—especially olives—over the past three years, an agricultural engineer from the town, who asked to remain anonymous, told Syria Direct. “Many turned to growing cereals and legumes, while others replanted other types of fruit trees that are more resistant to climate and environmental factors, and more adapted to water shortages and disease,” he added.

One official at the regime’s Daraa Agricultural Directorate echoed the engineer, adding “the phenomenon of replacing olive trees and grapevines with wheat and barley crops” is due to “the lack of water sources to irrigate the trees.” This is especially prevalent in the eastern Daraa countryside, where “vast areas of olive trees have been uprooted,” he added.

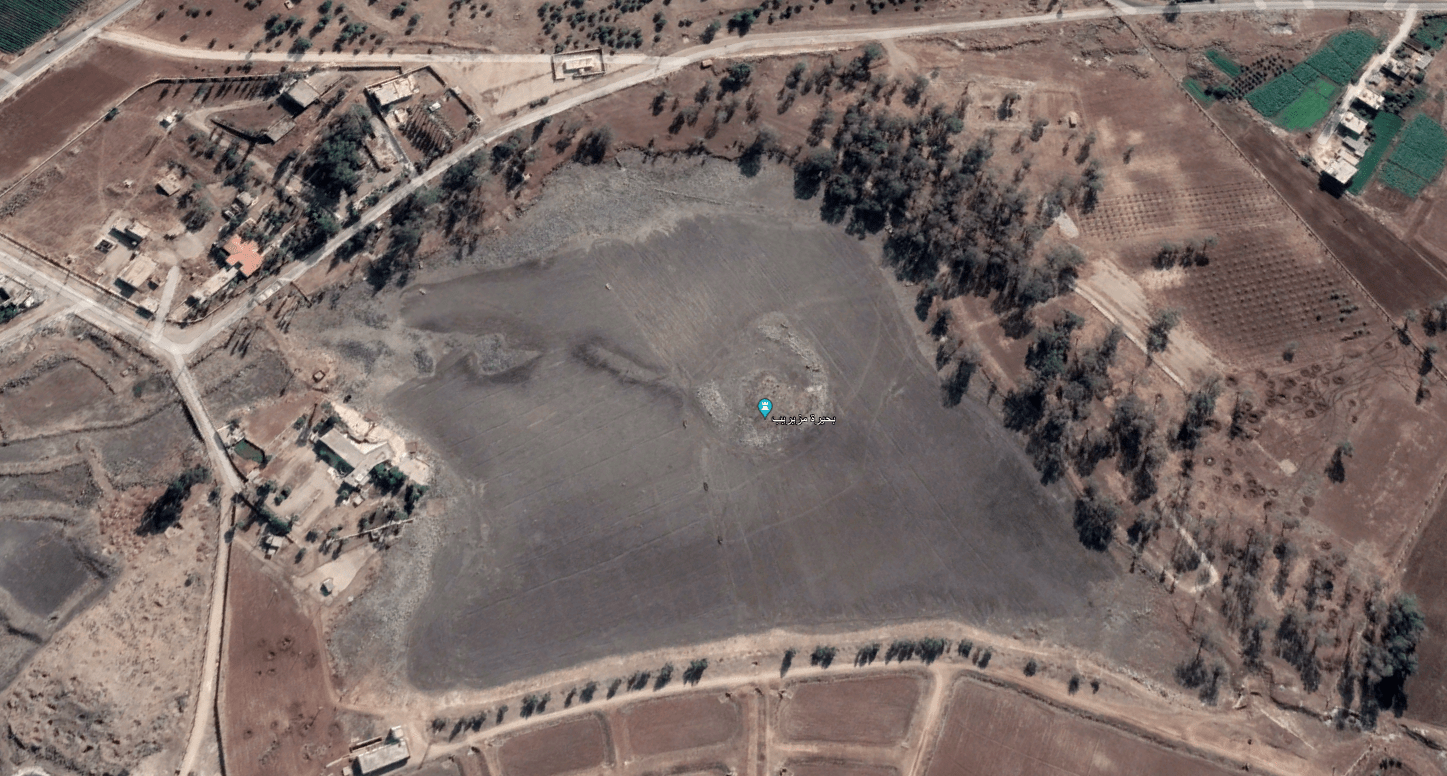

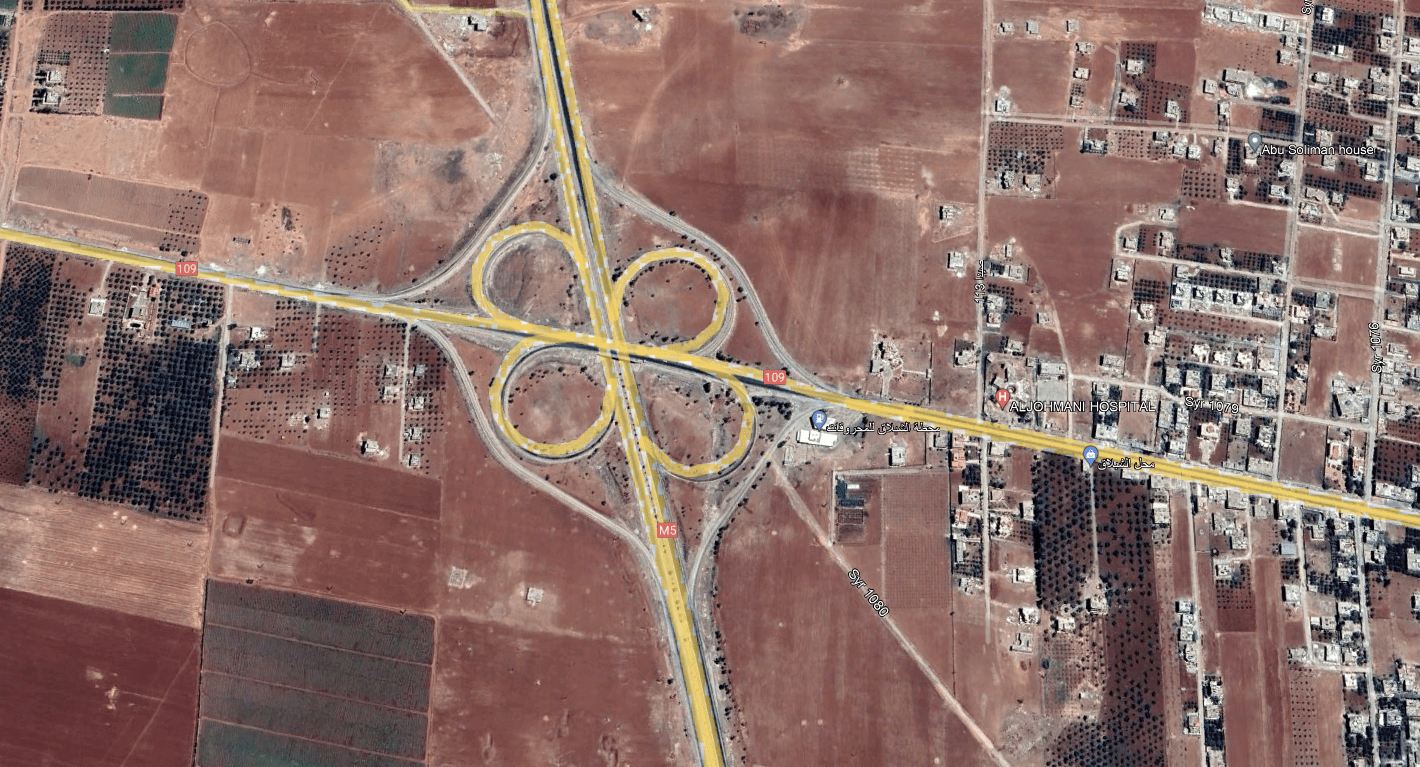

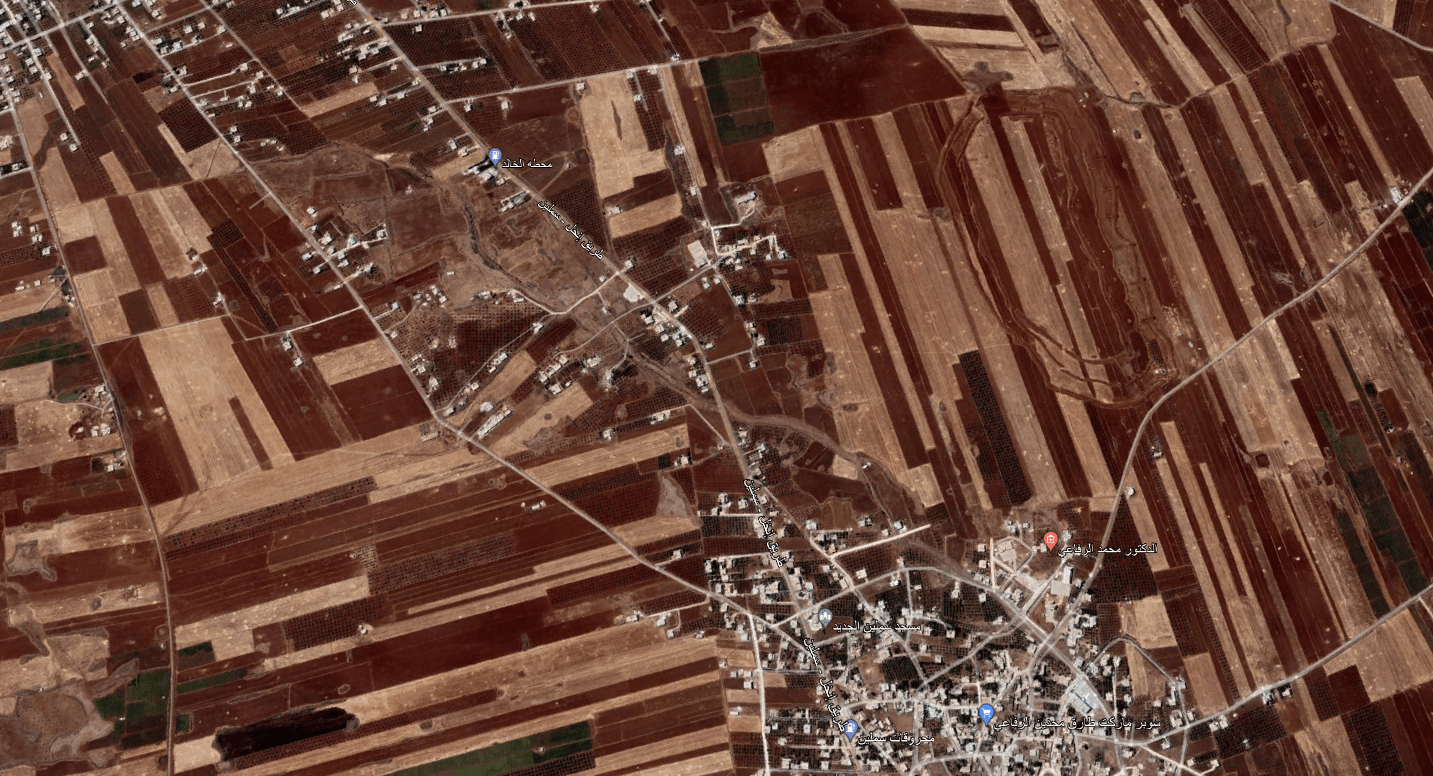

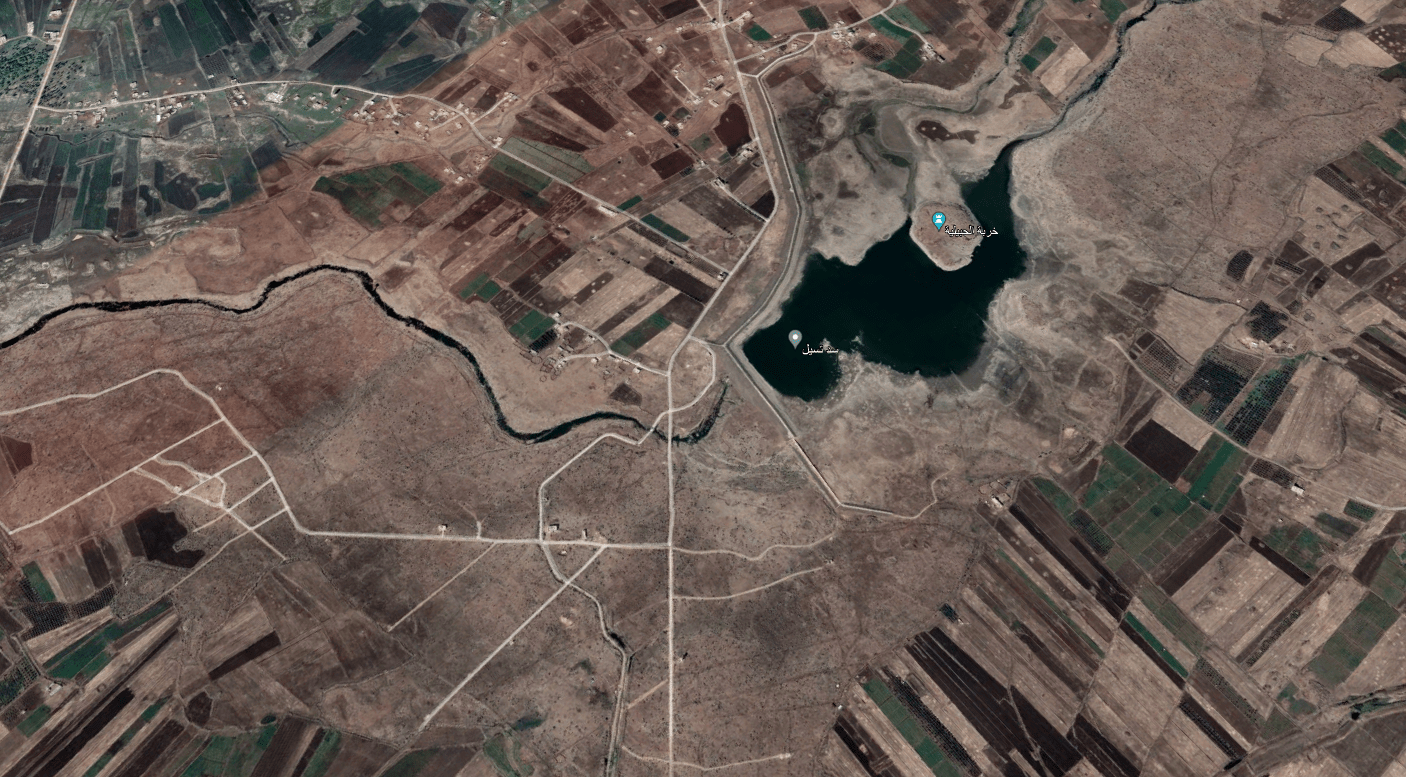

Satellite images from August 2011 (left) and November 2022 (right) show extensive deforestation at the national park in Tseel, a town in the western Daraa countryside. (Google Earth)

Forest trees

Before Daraa’s fruit trees were uprooted, its forests were plundered. Even on the roadsides of cities and towns, trees steadily disappear. “Hardly a day goes by without me noticing a tree completely or partially cut down,” Naim, a man living in Inkhil, told Syria Direct.

In Inkhil, most trees planted on the edges of a seasonal stream that runs through the city were cut down in recent years. Those trees “protected the soil from erosion, preventing the stream from widening or receding,” agricultural engineer Abu Yassin said. If the streambed erodes or widens, nearby homes and farmland could be flooded during heavy rains, he added.

Naim, who is in his 30s, has no doubt that cutting the trees down is an attack on the environment, but understands the motivations of those responsible. “You can’t see your children dying from cold, so you’ll cut down a tree even if it is decades old,” he said.

Small pits mark the places where trees once stood in al-Muzayrib, a town in the western Daraa countryside, before they were felled, reportedly by local armed groups, 20/3/2023 (Horan Free League)

In the neighboring western Daraa towns of al-Muzayrib and al-Yadouda, near the Jordanian border, a local militia linked to Syrian military intelligence has made a trade of removing trees from public land and selling them to firewood traders, the Horan Free League, a local pro-opposition network in Daraa, reported last March.

In late October 2023, extensive logging activity impacted all the forest trees in the al-Mashrou area near the western Daraa town of Tal Shahab, local news outlet Daraa 24 reported. The outlet also accused a local armed group of being responsible.

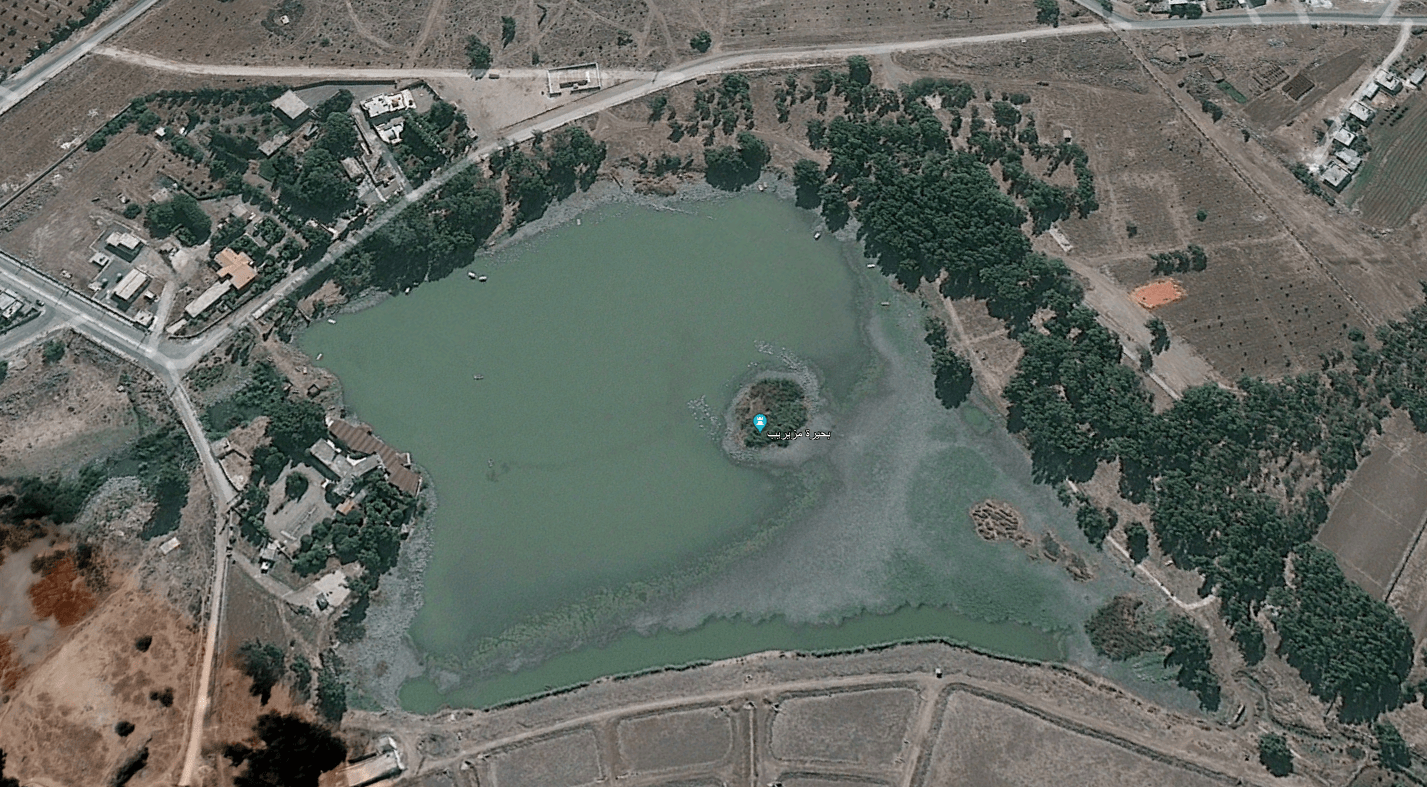

Satellite images show that a number of trees surrounding the al-Muzayrib Lake in western Daraa province were removed between October 2011 (left) and November 2022 (right). (Google Earth)

Wassim al-Ahmad (a pseudonym), who lives in western Daraa, said logging in the area’s forests, including the vicinity of regime military barracks, is ongoing and has accelerated since 2023. In the Tal Ashtara woods, located between the towns of Tseel and Adawan, as well as in areas along the Masaken Jileen road, the al-Muzayrib-al-Yadoudah road and the Jileen Research Station, “the remaining trees are currently being felled,” al-Ahmad explained.

No single group is responsible. “Those doing the logging are ordinary people, groups under former opposition commanders, settlement factions and military security,” al-Ahmad said. “Groups from the military security-linked settlement factions are cutting down trees in the Tseel forest,” he added.

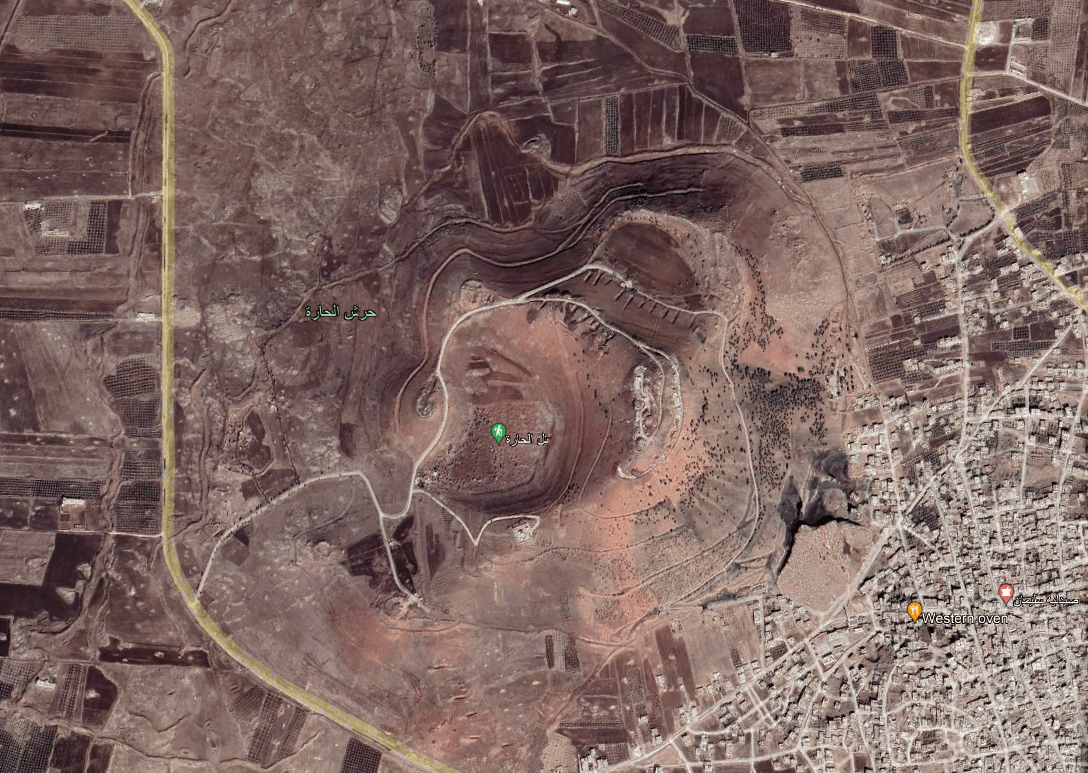

Additionally, “the eastern and southern portions of the Tal al-Hara woods are being logged these days,” Abu Ihsan, who is from al-Hara, a town northwest of Jassim, told Syria Direct. The southern and western sections of the woods previously saw extensive logging in late 2014.

Abu Ihsan described logging in southern Syria as systematic and led by regime forces— which regained control of Tal al-Hara in summer 2018—alongside affiliated groups. “Nobody can cut trees without permission or cover from them, or at least working in partnership with them,” he said.

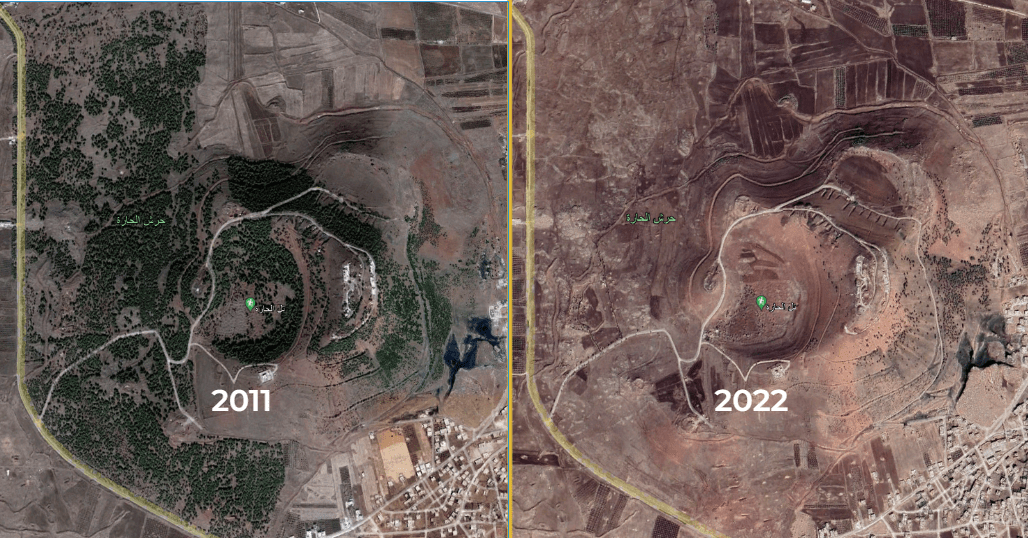

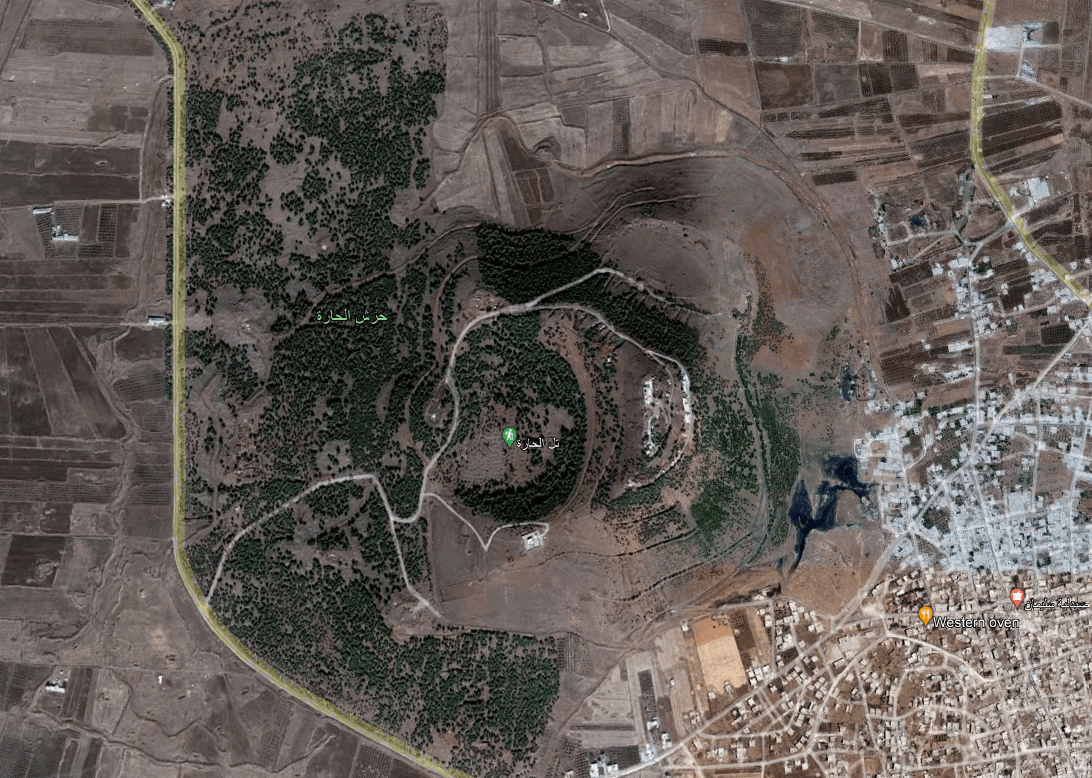

Satellite images show the Tal al-Hara woods, in northwestern Daraa province, were all but stripped bare between October 2011 (left) and November 2022 (right). (Google Earth)

Before 2011, planted forests covered 10,324 hectares of Daraa province, alongside the natural, 300-hectare Wadi Maariya forest. Most of these wooded areas were spread throughout the western countryside, an official source at the Daraa Forestry Department, which is affiliated with the regime’s Daraa Agriculture Directorate, told Syria Direct.

Forest sites saw “major encroachments over the years of the crisis,” but “the volume of encroachments last year was lower than in the early years,” the source said.

Last year, the Daraa Forestry Department’s Daraa and Nawa ranger stations filed 52 incident reports, most of which were “against unknown” individuals, the official said. “Most encroachments took place at night, at the hands of unidentified armed groups.”

After an encroachment, the forestry department files a report, and the case “remains open until the perpetrator is identified,” the source said. “The courts then follow up on it until there is a final ruling and the perpetrator is referred to the judiciary,” the source added.

An official at the Daraa Agriculture Directorate said the number of forest encroachments fell in 2023, compared to the first years after the Syrian revolution, due to “the state regaining control of the province and controlling the chaos in it.” Still, he expected the true number of encroachments to be “much greater than the number of reports that have been recorded.”

Contrary to the two regime-affiliated sources’ narrative, agricultural engineer Abu Yassin estimated that attacks on trees on public land have increased by 90 percent since 2019, coinciding with Damascus regaining control of the area. He attributed this to “the absence of monitoring and the authorities’ role, as well as people’s increasing need to use firewood for heating and cooking.”

“A small family needs around 200 liters of fuel for heating, at a minimum, during the winter season. This number goes up to 500 liters for large families,” Abu Yassin said. The Damascus government provides subsidized fuel, but “only 50 liters, and you might only get it at the start of winter or the end, depending on availability. People don’t rely on the [fuel] subsidy for heating.”

Since “most families in the city are low income, and more than 80 percent cannot buy fuel for heating,” many have been driven to “cut down public trees, in some cases encroaching on fruit trees and wooden telephone poles,” he said.

In Jassim too, “80 percent of public trees were attacked over the years of the war,” agricultural engineer Ibrahim Sayyah (a pseudonym) said. He noted that tree cutting, “including forest trees, continues.”

The Daraa Forestry Department was not able to survey the scale of damage to forested areas for years during the war, the official said. The department has managed to “renew 70 percent of the spaces that were attacked during the years of the crisis,” he added. Additionally, “some forest sites regenerated after they were cut down” as “most of Daraa’s forests are broad-leaved trees, such as eucalyptus,” which can regenerate from a stump.

The same official explained that attacks on forests in Daraa province are concentrated in the Tal al-Ara woods, the area of Sahm al-Golan, Jileen, al-Muzayrib, and the al-Fawwar spring, as well as along the old Damascus-Daraa highway.

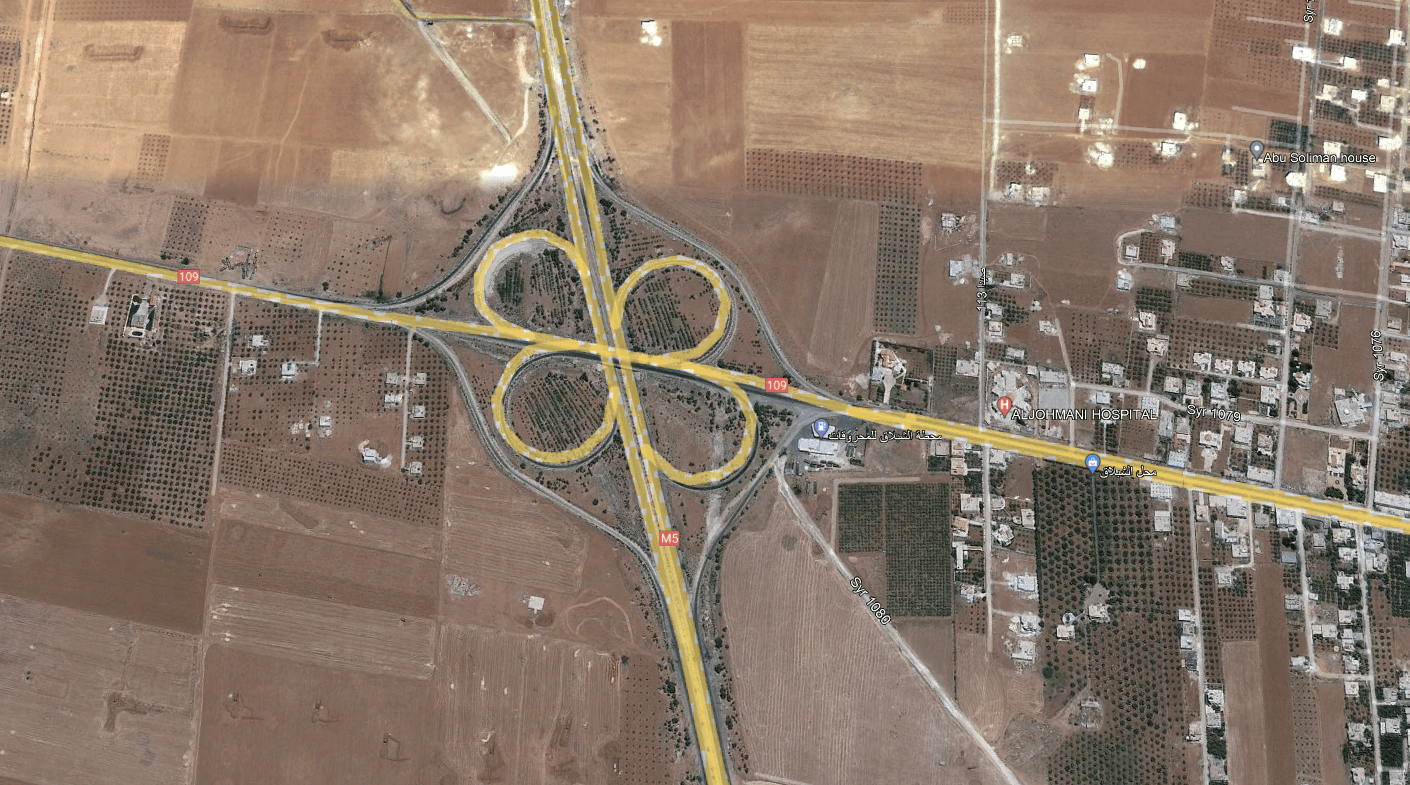

Satellite images show that trees in the Jisr Saida area in eastern Daraa province have been cut down between July 2011 (left) and July 2022 (right). (Google Earth)

Where is the state?

In late December 2023, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad issued Law No. 39 of 2023, known as the “New Forests Law.” It aims, according to regime media, to preserve and sustainably manage the country’s state-owned and private forests in partnership with civil society. The law also toughens penalties for attacks on forests.

Article 47 of the law states that “anyone who uproots, destroys or cuts down trees, shrubs or small shrubs in state forests without prior authorization from the Ministry shall be punished with temporary imprisonment and a fine of five-to-10 times the value of the damage caused.” Those who commit similar acts in private forests without authorization face “imprisonment from three months to two years, and a fine of twice the value of the damage caused.”

If “the acts specified…occur outside state forest or private forest, the penalty shall be a fine of SYP 1 million for each tree, shrub or small shrub” destroyed without prior approval.

Although the new forests law increased most penalties, “the state is not actually able to protect green cover, especially in areas outside its true control in Daraa, such as the Tseel forest, which is undergoing intensive deforestation, and forestry officers have not been able to get control of it,” one lawyer in Daraa told Syria Direct on condition of anonymity.

“Police officers cannot carry out their work outside the station, even if it concerns just a simple report,” the lawyer explained.

He believes “the state does not want to prevent the phenomenon of logging to prove there is a state of chaos” and because “it cannot provide [other] means of heating and cooking for citizens.” In turn, “the local community cannot protect plant cover because there is no enforcing body at its disposal to prevent people from cutting,” the lawyer added.

The lawyer noted that attacks are not limited to forest trees. “Some are cutting olive trees without the consent of their owners and selling them as stolen firewood,” driving some farmers to “cut down the trees on their land themselves because they fear they will be stolen and they cannot water them.”

If the state is serious about limiting tree cutting, “it must provide people with heating and cooking fuel, to prompt them to do without firewood,” the lawyer added.

Satellite pictures show many fruit trees were removed south of Inkhil city in the northern Daraa countryside between August 2011 (left) and December 2022 (right). (Google Earth/Syria Direct)

Environmental impact

Fruit and forest trees are carbon sinks, absorbing carbon dioxide and pollutants from the air and releasing the oxygen necessary for breathing. They provide an aesthetic and touristic benefit, to say nothing of economic returns from fruits, the Daraa Agriculture Directorate official said.

“Trees create a clean environment and regulate temperatures. Especially with high temperatures in the summer season, we notice that wooded areas have a milder atmosphere,” he said.

Trees also play a key role in “countering climate change,” the Daraa Forestry Department official said. “The larger the area of trees, forests and forest sites in a given area, the better the rainfall amounts and the better the climate.”

Eliminating trees leads to “colder winters and hotter summers,” agricultural engineer Sayyah agreed. If the government fails to limit logging, it should “implement afforestation campaigns and encourage people to plant trees by distributing saplings for free,” he said.

Agricultural engineer Abu Yassin echoed the need to plant new forests, noting that the last afforestation and sapling distribution project in Inkhil was carried out by the opposition-affiliated Free Daraa Provincial Council before the regime retook control in the summer of 2018.

“Forests and trees are the breathing lungs of cities, and they bring rain,” Yousuf Maslamani, the chief air quality and climate change expert at Bureau Veritas, a global company providing inspection, safety and environmental protection services, told Syria Direct. Logging and encroaching on forests means “arid lands prone to desertification, with a climate that is volatile in summer and cold in winter.”

Trees “help mitigate the effects of climate change,” Maslamani added. This is why “in Western cities, you find there are requirements and distributions for the percentage of green spaces in the city, while in our cities there are not enough green spaces in the first place.”

From an environmental perspective, he did not find a justification for farmers to “replace fruit trees with seasonal crops, because the latter remain green for a specific season, unlike trees that may last longer or year-round.” However, “before holding people accountable, we must provide sustainable alternatives,” he added. “Poverty and the environment do not go together.”

Abu Qassem is aware of the environmental and climate repercussions of cutting down his grove, to say nothing of his personal attachment to his olive trees. “I know them, tree by tree,” he said. Still, “I had to sacrifice my trees or my son. I chose my son.”

This investigation was produced with financial support from the European Endowment for Democracy (EED). Syria Direct is solely responsible for its contents, which do not necessarily reflect the views of EED. It was originally published in Arabic and translated into English by Mateo Nelson.