Will Raqqa’s church bells ring again?

More than five years after the Islamic State was driven out of Raqqa city, many Christians who fled the city under its rule have not returned. Today, only a few dozen members of the community remain. Why?

6 June 2023

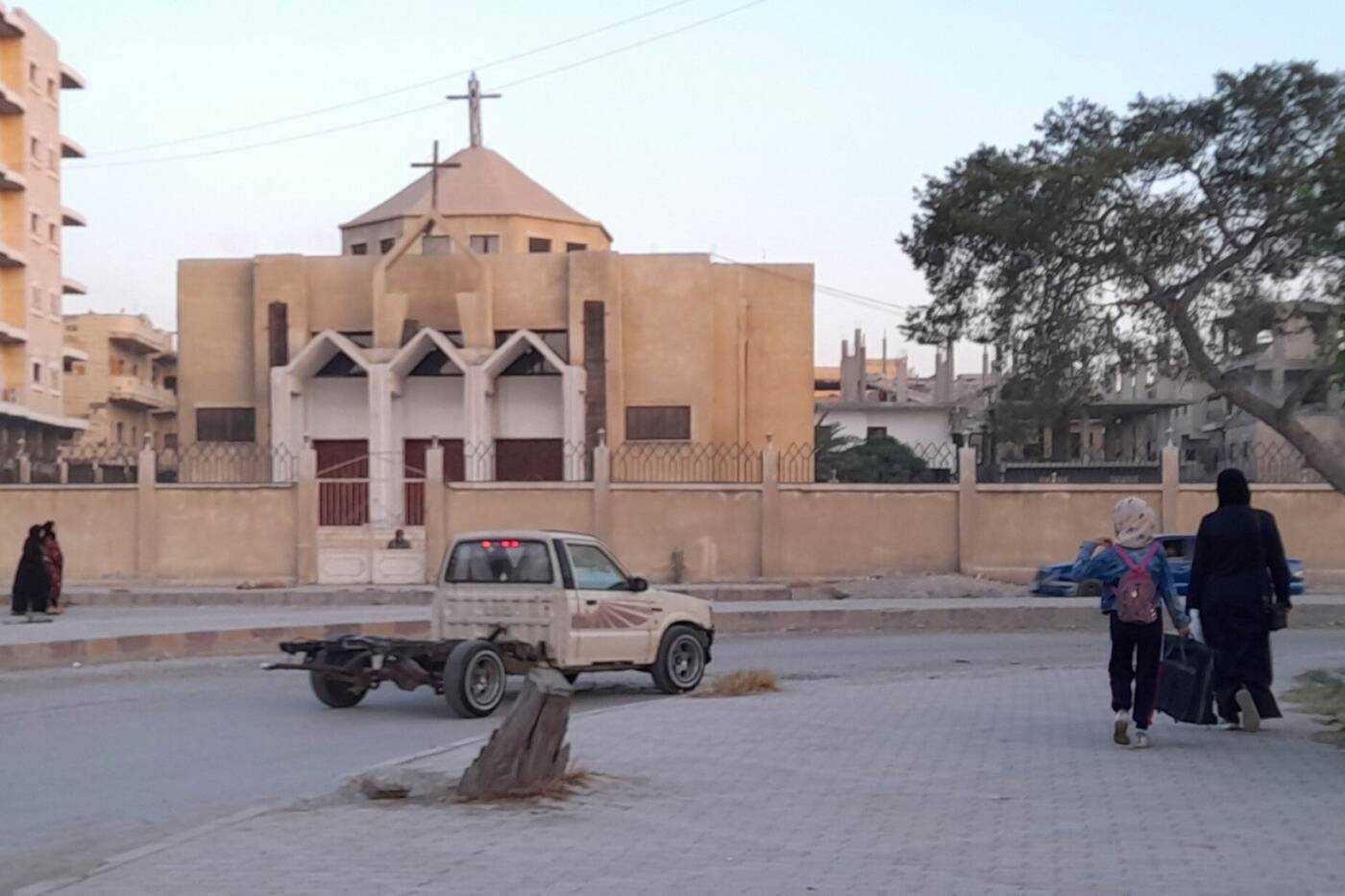

RAQQA — Strolling south from al-Naim square in the heart of Syria’s northeastern Raqqa city, past the former teachers’ syndicate, brings you to al-Rashid Park beside the Martyrs’ Church. In this place sits a man, his skin tanned, for hours every day.

Upon approach, he seems wary of passersby, giving the impression of irritation. Speaking to him shows otherwise: a kind man who enjoys chatting and answering questions. His name is Mujhem, and he was appointed by the Raqqa Civil Council’s Religious Affairs Institution to guard the church, which was restored and officially reopened in May 2022.

“Christians are part of Raqqa. They should be respected, along with their beliefs,” Mujhem told Syria Direct. He is confident in his task guarding the church, despite occasionally facing insults from “some boys,” which he attributes to “the lingering influence of [Islamic State] IS ideology, which will take years to fade.”

A few meters south of the Martyrs’ Church sits the Abu Hurairah Mosque, which locals call the Circassian mosque. Further to the southwest, the rubble of a ruined structure reveals a wall adorned with colorful paintings. This was once the Our Lady of the Annunciation Church, destroyed by international coalition airstrikes in August 2017 during the battle against IS in the capital of its self-proclaimed caliphate.

In mid-October 2017, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), backed by the international coalition forces, declared the expulsion of IS from Raqqa city. But more than five years later, the city’s Christian population is virtually nonexistent. Only a small number of those who fled the city during its years under IS control have come home.

‘They went extinct’

When first asked about his community over WhatsApp, Murad*, a Christian from Raqqa, responded simply: “They went extinct.” His hurt bigger than could be expressed in text messages, he asked to meet in person, at the home of a friend in Raqqa’s al-Firdous neighborhood.

Murad was a painter when IS took control of Raqqa in late 2014, but gave up his profession. The organization’s ideology deemed it a violation of Islamic law, and he feared for his safety. Even then, IS converted his shop in a basement in the city center into a Sharia court for the hisba, the organization’s morality police.

When IS entered Raqqa, its church bells stopped ringing. The organization imposed strict restrictions on Christians as it transformed the city into its capital in Syria. Christians had to pay an additional jizya tax, and were prevented from practicing their faith. As a result, many left, leaving Raqqa for Syrian cities outside IS control or fleeing the country altogether.

Raqqa’s historical Christian community can be divided into two groups. The first has lived in Raqqa since it was established. The second consists of Armenians who fled the genocide perpetrated by Turkish nationalists against Christian minorities in the Ottoman Empire at the start of the 20th century. Survivors fled to a number of Syrian provinces, including Raqqa, settling in its capital city as well as Tabqa and Tal Abyad.

Before 2011, 800 Christian families lived in Raqqa city, with an average of six members per family, or a total of around 4,800 people, according to figures provided to Syria Direct by the Assyrian Observatory for Human Rights, a Sweden-based center focused on Christians in the Middle East. Today, 13 Christian families live in Raqqa, with an average of two members per family, for a total of roughly 26 people, according to the Observatory.

“Christians who have returned don’t include any children or young people,” one local Christian source in Raqqa told Syria Direct. “Most of them move between Raqqa and other areas—they don’t permanently live in the city.”

The beginning of the end

On March 5, 2013, the opposition Free Syrian Army (FSA) took control of Raqqa. The city was the first provincial capital to fully come under the FSA command, but Islamist factions such as Ahrar al-Sham and Jabhat al-Nusra soon rose to dominate the military scene.

Months after Raqqa left regime control, IS began to infiltrate the city, using the Islamists’ presence as an opening. The group carried out a series of assassinations and kidnappings, culminating in the abduction of the Italian priest Paolo Dall’Oglio in late July 2013, whose whereabouts remain unknown to this day.

Father Paolo, an Italian Jesuit priest, served at the Deir Mar Musa al-Habashi monastery north of Damascus before the 2011 revolution, and was exiled by the regime in 2012 for supporting the uprising. He returned, entered Raqqa city on July 23, 2013 during battles between IS, opposition forces and Jabhat al-Nusra and disappeared days later.

In early 2014, IS seized full control of Raqqa, pushing other factions to the suburbs of Aleppo city and targeting those who did not pledge allegiance to the group. Its forces began imposing strict rules on the residents of Raqqa, Muslims and Christians alike, imposing the niqab for women and mandating beards for men.

In late February 2014, IS announced that it had reached an agreement intended to “ensure the safety of Christians,” without naming another party to the agreement. The “agreement” consisted of 12 rules, including imposing the jizya tax on Christians and prohibiting the display of crosses in markets or places where Muslims were present. It also banned using loudspeakers and performing rituals outside churches.

“I would mentally prepare myself before stepping out onto the streets,” said Murad, who stayed in Raqqa until May 2017. While many of his peers left Raqqa in the first months of IS control, he only left for Tabqa after the SDF expelled the group from his home city. He continues to move between Tabqa and Raqqa today.

During the battle against IS, churches in Raqqa were bombed by international forces, including an August 2017 strike in the al-Thakana neighborhood that destroyed the Church of Our Lady of the Annunciation. Since taking control of the city, IS had converted Raqqa’s churches into centers of its own. The Church of Our Lady of the Annunciation was used as a general administrative office, while the Armenian Martyrs’ Church was converted into a proselytizing office, according to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights (SOHR).

A one-way trip

Of the three sects that make up Raqqa’s Christian community, Roman Catholicism is the largest, centered at the Church of Our Lady of the Annunciation in al-Thakana. Armenian Catholics gather at the Martyrs’ Church near al-Rashid Park, while the Armenian Orthodox community worship at a church inside the al-Hurriya School on al-Quwatli Street.

Historically, Armenians were renowned for their skill in craftsmanship and industry, with the majority of Armenian Christians in Raqqa living in al-Sinaa, the city’s industrial neighborhood.

Muhammad Jamil, a former guard in the industrial zone before the 2011 revolution, recalls how “al-Sinaa was bustling on Fridays, with all the shops open, while it was deserted on Sundays, indicating the large number of Christians.”

Speaking to Syria Direct, Jamil pointed into the distance, recounting: “Here, there was an Armenian. Next to him was another Armenian, and opposite them was the shop of their relative, and further down their cousin’s shop…this shop belonged to two brothers.” Most of those he mentioned “worked in diesel engine maintenance, but they all left Raqqa and had to sell their properties,” he said with a sigh.

Among the reasons why many Christians have not returned to Raqqa and other cities in the province, such as Tabqa, is that “SDF-affiliated factions have prevented them from returning to their homes, with the Northern Democratic Brigade currently controlling the homes of Christians in Tabqa,” Murad said.

According to a December 2020 report by Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ), the Northern Democratic Brigade unlawfully seized 80 houses in Raqqa city. STJ cited a source in the People’s Municipality as saying that, based on complaints filed between late 2019 and June 2020, around 1,200 homes in Raqqa were seized by SDF-affiliated military entities.

But more importantly, tribalism and sectarianism, coupled with intolerance instilled by IS, have also prevented the return of many Christians who have chosen instead to sell their homes at low prices. Murad, who monitors Christian properties in the area, told Syria Direct that the number of homes in Raqqa city owned by Christians declined from 237 to 96 residences in recent years.

Those who have sold their homes in Raqqa “cannot buy again, because of the sharp increase in real estate prices, and because they feel that society does not accept them, after IS implanted the principle of rejecting the other,” he said.

Nobody to ring the bells

In a reverse migration, George*, a young man from Tal Abyad in the northern Raqqa countryside, was displaced from his home to Raqqa city in late 2019. He fled Operation Peace Spring, an offensive by the Turkey-supported Syrian National Army (SNA) against the SDF in Tal Abyad and Ras al-Ain. George, an Armenian, later opened a shop in Raqqa al-Sinaa neighborhood.

The story of Raqqa’s Christians echoes that of their counterparts in Tal Abyad. Once inhabited by around 150 Christian families, most of them fled after IS took control of the province. Those who returned were displaced yet again when Turkish-backed opposition forces took over, as in George’s case.

Since arriving in Raqqa, George has encountered only a handful of fellow Christians in the city. He attributed this to “the lack of a regular meeting place for Christians, which has contributed to a sense of disconnection and increased fear among the community, particularly among the women.”

On November 11, 2021, the Raqqa Civil Council announced the Martyrs’ Church would be reopened following the completion of restoration work, which began in 2019. The church was damaged during the battles between the SDF and IS in 2017, and it was officially reopened in May 2022.

But while the Martyrs’ Church is open, “its bells remain silent and prayers are not held, because there is no priest to conduct the prayers,’’ Masis*, an Armenian Catholic in Raqqa, told Syria Direct. He pointed to “the clergymen’s fears, and the failure of the diocese to appoint a suitable priest for the church.” Masis prays at home, only making occasional visits to the church.

Murad noted that the issue extends beyond clerics alone. Citing a conversation between Christian clerics he was present for during a funeral in Hasakah province, he contended that some stipulate “the return of the regime to Raqqa, and its flag being raised there,” as a condition for return.

Churches and clubs “play an important role in bringing Christians of the same sect together and fostering connections among them,” Murad said. “Without regular prayers in the church, and with no active clubs, Raqqa’s Christians have become scattered individuals who don’t know one another,” he added.

“This calls us to sound the alarm, warning that Raqqa may lose part of itself in a few years.”

*Pseudonym used for security reasons.

This report was produced as part of Syria Direct’s MIRAS Training Program for early-career journalists in northeastern Syria. It was originally published in Arabic and translated into English by Nouhaila Aguergour.