Yazi Nahum: The last Jew in Qamishli tells her story

Yazi Nahum, the last Jew in northeastern Syria’s Qamishli, reflects on her life, her marriage to a Muslim man and the remaining traces of her city’s lost Jewish community.

13 June 2023

QAMISHLI — Yazi Nahum, the last Jew in Qamishli city, shares recollections of her life and the Jewish community in northeastern Syria, now a distant memory.

Sixty-one years ago, Nahum eloped with Bahgat Darwish, a young Muslim man, despite her family’s disapproval of their relationship. The two were married in 1962 in al-Latifiyah, a village northeast of Qamishli, with the help of a man named Salim, the local Kurdish mukhtar—the administrative chief of the village. Salim arranged for a local mullah to marry them under Islamic law, 78-year-old Nahum recalled.

The next morning, Nahum’s family filed a complaint at the Qamishli police station, stating that “a 19-year-old Muslim man had kidnapped a 17-year-old Jewish minor girl,” she said. Acting on the complaint, the police arrested Darwish. He was imprisoned for a month before he was released and reunited with his wife.

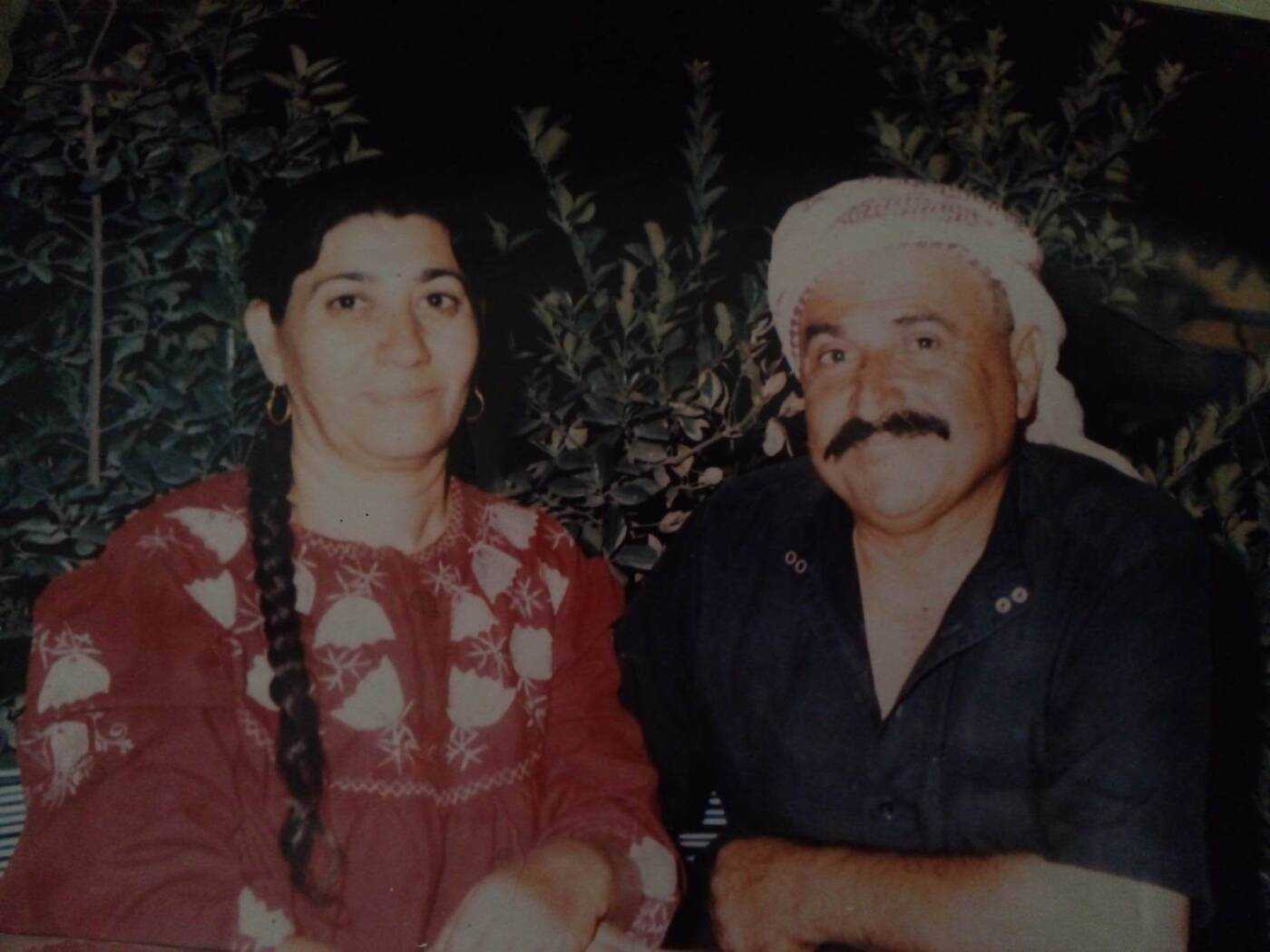

An undated picture of Yazi Nahum with her husband, Bahgat Darwish, (Yazi Nahum/Slava Younis/Syria Direct

Nahum’s family disapproval of her marriage was limited to the circumstances surrounding it, she said, not the broader relationship between Qamishli’s Jews and other communities at the time, she said.

“There were no divisions among sects in our Qamishli neighborhood—there was good will between Muslims, Jews, Christians, Kurds and everyone else,” according to Nahum. Social events had long “brought neighbors together, regardless of their religion—Assyrians, Christians and Muslims—and women and their daughters would stay up together, as if they were part of one big family.”

The Jewish presence in Qamishli traces back to the early 20th century, when around 150 Jewish families migrated from Nusaybin, a town on the Syrian-Turkish border, to Qamishli, which was established under the French Mandate.

“By 1931, the Jewish community in Qamishli had grown to about 250 families. Their houses were mainly made of mud, like most houses in the city,” said Syrian thinker and writer Anis Hanna Mediwayeh, who lives in the city and was a contemporary of its Jewish community. “They built a synagogue where they would gather to pray, facing Jerusalem.”

In 1947, the Jewish community in Qamishli submitted a request to the Syrian Knowledge Directorate to establish a school for their children. Mediwayeh, who served as the school’s director, said it enrolled 80 students, but “closed down within a year of its establishment due to the outbreak of the 1948 war in Palestine and the ensuing establishment of the state of Israel.”

Before settling in Qamishli, Jews in Syria’s Jazira region—the northeasternmost part of the country—mainly lived in the areas of Qalaat Jaabar, Raqqa, Harran, Ras al-Ain, Nusaybin, Jazirat Ibn Omar, al-Mayadeen and al-Busayra, according to an article on the community’s history by Syrian researcher Muhannad al-Katea. By 1970, when Hafez al-Assad took control of Syria, less than 4,574 Jews lived in the country, 414 of whom were in Qamishli, according to Katea.

That year, Nahum’s family left Qamishli for Damascus, eight years after she married Darwish. She stayed behind, living with her husband—who died in 2013—and his family for decades. After she was disowned by her family, Nahoum’s in-laws “treated me like one of their daughters and respected my religious rituals and traditions,” she said.

Yazi Nahum stands in front of her house in Qamishli city, northeastern Syria, 6/7/2023 (Slafa Younes/Syria Direct)

Nahum never converted to Islam but, now in her seventies, regularly observes the Muslim tradition of fasting during Ramadan, and enjoys listening to her daughters recite the Quran. “I love all religions,” she said. “Worshiping God is a common thread among believers, regardless of their faith.”

Nahum had 14 children, two of whom passed away. “I raised them all following Islamic practices with the support of my husband’s family, who all respected my Jewish traditions, like staying away from the marriage bed for 60 days after the birth of a girl, or 50 days after the birth of a boy, and praying three times a day before sunrise,” she said.

Nahum still keeps traditions surrounding Jewish holidays such as Passover and Yom Kippur. “We have two [major] holidays, one in April or May and the other in October. We celebrate each for a week, during which we only eat meat, rice and eggs,” she said.

Before Qamishli lost its Jewish population, kosher meat was delivered to the city from Damascus and Aleppo. Sheep and chickens slaughtered by a specialized rabbi were “delivered to the Jews in Qamishli every other week on Tuesdays,” Nahum recalled. It was important for the animals to be free of defects, and that the slaughterer say the name of God while swiftly passing a knife across the animal’s throat only once, Nahum said.

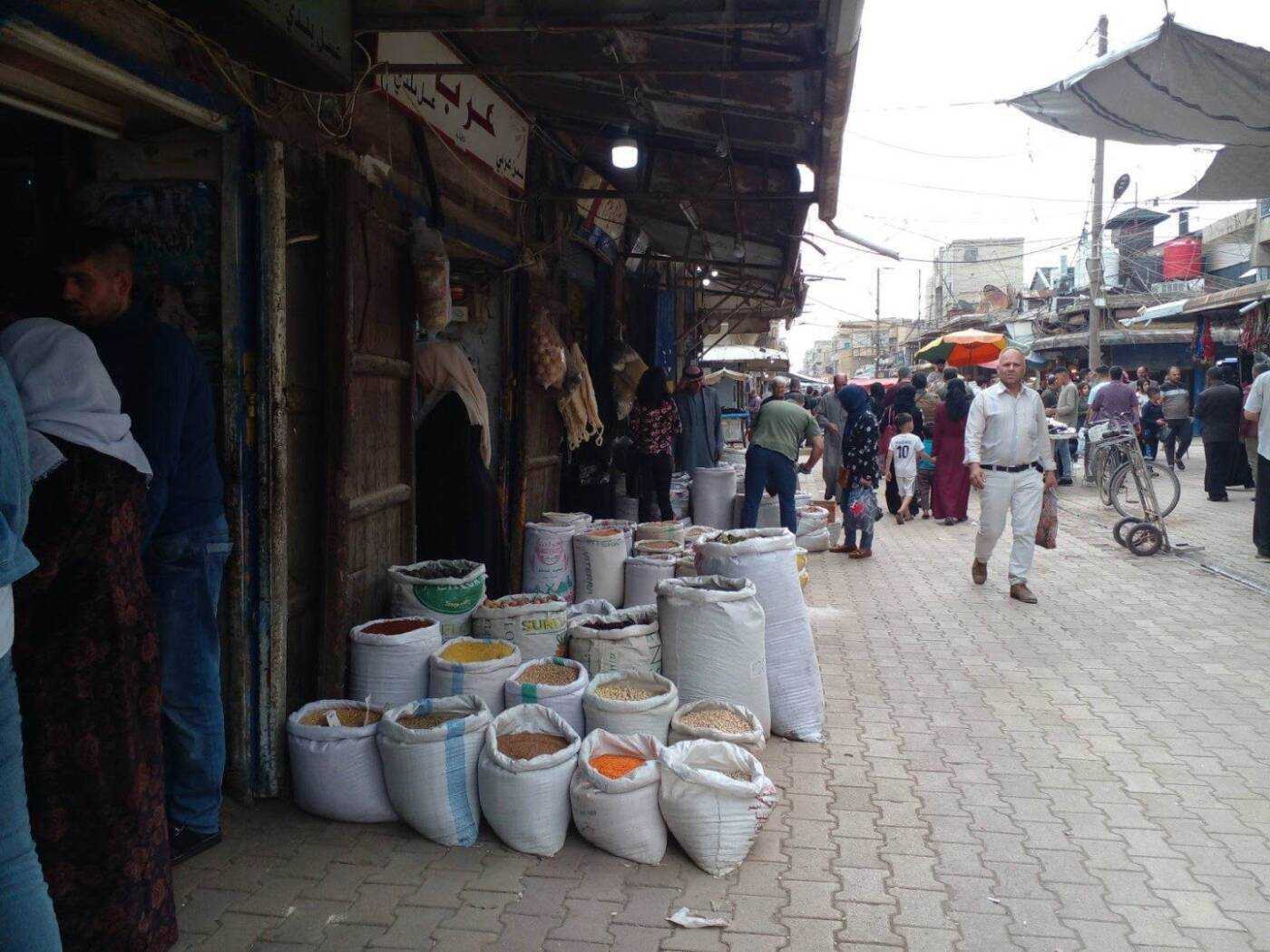

Nahum remembers Qamishli’s Ezra Market, also known as the Jews’ Market, which closed on Saturdays “as we couldn’t carry money, engage in buying or selling or light fires on that day.” Dating back to 1928, the market was one of the oldest in the city, serving as a commercial hub for its Jewish community and others until 1999, when most Jews had left Qamishli. In 1992 and 1994, Hafez al-Assad lifted decades-long restrictions on Jewish emigration from Syria, prompting a mass exodus.

Ezra bin Nahum bin Isaac, a merchant whose name remains tied to the market, was “known for his honesty, integrity and kindness among Arab and Kurdish clans from east to west, and many people borrowed money from him until the end of the season,” she recalled. “His house was always open to visitors, offering shelter to those who came from distant areas, including people from the opposite side of the city and even those who were sick.”

People strolling while others stand before shops in Qamishli’s Ezra market, 06/07/2033, (Slafa Younes/Syria Direct)

Ezra left Qamishli for the United States in the 1980s after selling his shop in the market, “provided that his name stayed on the banner, and he got what he wanted,” said Nahum. Ezra’s name remains on the shop’s sign today, preserved by its current owner.

Ezra’s name remains on the sign of his former shop, preserved on the banner in Qamishli’s Jews’ Market, 6/7/2023 (Slava Younis/Syria Direct)

According to Nahum, the Jews in Qamishli, including Ezra, gained renown for their trade activities, importing items like “dates, molasses, cigarettes and spices from Iraq, and buying goods from Aleppo and Damascus.”

“The Jews’ shops in Qamishli, with their wooden doors, are still registered under their names in official [state] records, while their homes remain intact but closed,” according to Mediwayeh.

All members of Nahum’s family, who left Qamishli in 1970, later migrated to the US and Israel in 1992. “I haven’t heard any news of them ever since,” she said. Still, in her religious practices and the remaining traces of Qamishli’s Jewish history, Nahum finds threads weaving her present with her past.

This report was produced as part of Syria Direct’s MIRAS Training Program for early-career journalists in northeastern Syria. It was originally published in Arabic and translated into English by Nouhaila Aguergour.