Darayya’s al-Khalij neighborhood ‘unoccupied, destroyed houses’ as hopes of return fade seven years into regime control

For former residents of Darayya’s al-Khalij neighborhood southwest of Damascus, hopes of return are fading as fears of property violations mount seven years after the regime retook control. Residents are not allowed to return, but many also find themselves unable to sell.

2 June 2023

IDLIB — Malek Muhammad* waited for the chance to return home for three years after the Syrian regime recaptured Darayya, his hometown in the southwestern suburbs of Damascus, in 2016. But after years of waiting, he gave up hope in 2019, and decided to leave Syria for Turkey instead.

The house he left behind lies in Darayya’s al-Khalij neighborhood, which became a first line of defense for the neighboring Mezzeh Military Airport against opposition military forces in 2012. To this day, despite regime forces regaining control of the entire area, former residents of al-Khalij are not allowed to return and rebuild.

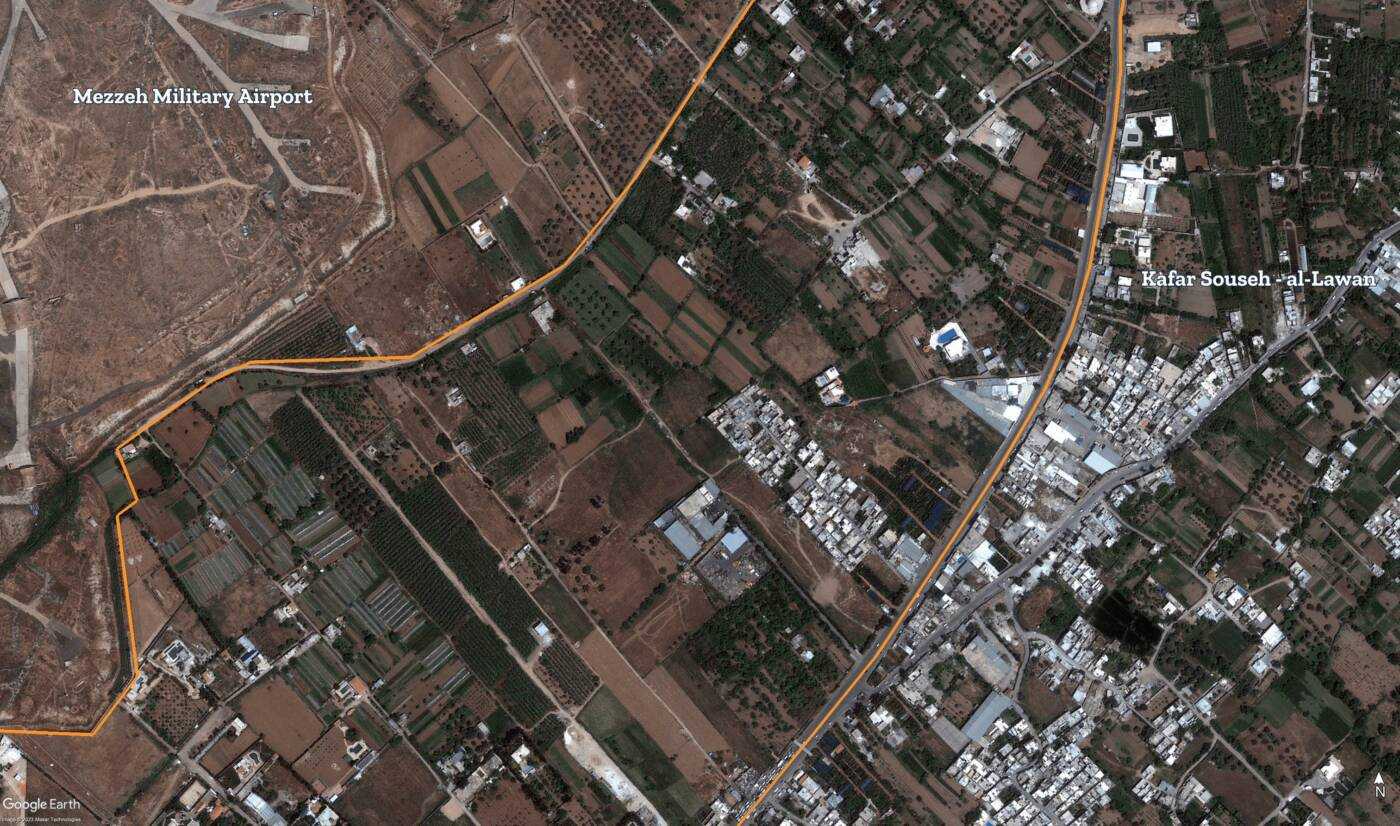

Muhammad, 29, fled his home in al-Khalij for regime-controlled territory in late 2012, when Damascus launched a military campaign against the then-opposition-held city. His neighborhood, located in the northeastern part of Darayya and stretching to the Mezzeh Military Airport, had become a heavily contested battleground. Regime forces demolished houses in al-Khalij and encircled it with an earthen berm, several opposition military sources who were present and witnessed the battles at the time told Syria Direct.

Following years of siege and barrel bombings, the Syrian regime took control of Darayya in August 2016 under a surrender agreement stipulating that opposition fighters leave the area, along with dozens of civilians, for northwestern Syria. Nearly seven years later, al-Khalij remains a neighborhood of “unoccupied, destroyed houses,” a current resident of the city told Syria Direct, requesting anonymity for security reasons.

“People are only allowed to enter the neighborhood to visit on foot,” the Darayya resident, who recently visited al-Khalij, said. “Rubble has not been cleared, services have not been restored, and the municipality responsible for civilians’ return has not included it in its plan” for reconstruction, he added.

Satellite images of the al-Khalij neighborhood of Darayya city, in Reef Dimashq, show widespread destruction and lack of treecover in 2022 compared with its state in 2011. (Google Earth)

Muhammad’s house in al-Khalij—or what remains of it, as it was largely destroyed in his absence—is still legally registered under his ownership in official state records, according to a lawyer in Damascus he contacted. But he is not allowed to return and repair it. Today, he is prepared to “sell it for $1,000, if I can find a buyer, though it was worth $20,000 before it was destroyed.”

Deferred ownership

In mid-2018, two years after retaking Darayya, the regime began to allow vetted former residents to return to certain neighborhoods. “Restoration efforts and real estate sales picked up somewhat, albeit at prices below the properties’ actual value,” the owner of a real estate office in the city told Syria Direct, requesting anonymity for security reasons.

Because most of the original owners are absent, most property transactions in Darayya are carried out through sales contracts without officially transferring ownership, the same source said. Changing ownership through the notary public or the courts can be “complex,” the real estate office owner said, especially when one of the parties to the sale is absent. The result is “indefinite delays in transferring ownership, which has contributed to falling real estate prices in the city,” he added.

In Darayya, real estate is priced and categorized based on its condition. Property categories include “barren land, a house with rubble, a house cleared of rubble and a stripped apartment [without cladding],” the real estate source said. An additional category is “looted,” referring to a residence that has been stripped of its electrical wiring, tiles, marble, doors and windows, but not demolished.

In al-Khalij, unlike other neighborhoods, there have been no property sales or purchases, though many houses are available for sale at attractive prices, according to the real estate office owner. “Buying a property in al-Khalij is like buying a fish in the water,” he said. “It’s a sale on paper—the buyer may not be able to take possession of the house for as long as they live.”

But Mazhar Sharbaji, the former head of the Darayya City Council from 2003-2005 whose family owns property in al-Khalij, said there are people buying property in al-Khalij, but not ordinary buyers. He contended “there is real estate activity in the al-Khalij area through middlemen linked to the security agencies,” adding that “the buyers are regime officers and officials, since they know what the fate of the area will be.”

“Strangers are invading the area,” making use of “people’s need for money and loss of hope of reclaiming their houses there,” Sharbaji, who currently lives in Turkey, added.

Satellite images of the southern section of Darayya’s al-Khalij neighborhood in Reef Dimashq show the difference between May 2011 and February 2022. (Google Earth)

Shifting municipal plans

Administratively, responsibility for rebuilding Darayya and restoring basic services lies with the Daraa City Council as “the implementing body,” Sharbaji said. But in reality, “it has no power or authority over al-Khalij, which has come under the protection of the Mezzeh Military Airport security forces,” he added.

Darayya’s redevelopment is “likely to be influenced by three factors,” Sharbaji said. First, the eastern part of the city was impacted by Legislative Decree No. 66 of 2012, which designated two development zones as part of Damascus city’s general plans for the development of areas of unauthorized and informal housing. One of these zones, known as Marota City, includes lands originally belonging to Darayya that “are now part of the development zone, which belongs to Damascus,” al-Sharbaji said.

Second, Darayya’s al-Khalij neighborhood is unlikely to see its former residents allowed to return long-term and rebuild, al-Sharbaji added. And a third part of the city, the Sakina Shrine, is a religious site now “under Shiite control,” he said.

Satellite images of the northern section of Darayya’s al-Khalij neighborhood in Reef Dimashq show the difference between May 2011 and February 2022. (Google Earth)

Al-Khalij neighborhood “is categorized as an informal housing area with a high percentage of structural damage, and is included in the reconstruction plan issued by the Syrian Ministry for Public Works and Housing on April 24, 2018,” Manhal al-Khaled, a Syrian lawyer specialized in housing rights and real estate ownership, told Syria Direct. According to the plan, al-Khalij is “devoid of houses, a ‘blank page’—the regime does not acknowledge the existence of housing in it,” he explained.

This categorization reinforces concerns about the potential impact of Law No. 10 of 2018, which allows Damascus to create urban redevelopment areas across Syria and has sparked controversy in recent years surrounding the possibility of the law expropriating millions of people.

The worry is that, under Law 10, Damascus could declare al-Khalij a redevelopment zone, “ostensibly to address the issue of informal settlement, and then survey the entire area, converting individual ownership into shares, without compensating those who have lost their ownership documents,” al-Khaled said.

Unlike Darayya, satellite images from February 2022 show the eastern portion of the Reef Dimashq province city of Moadimiyet al-Sham show an increase in the number of buildings despite its proximity to the Mezzeh Military Airport in February 2022 compared to May 2011. (Google Earth)

These fears are amplified by the fact that “the majority of residents in the region are refugees and displaced people outside the government-controlled area,” he added. This makes it virtually impossible for them to object to any reconstruction decisions or plans affecting the area, since objections must be submitted to the municipality in person or through an official proxy.

Sharbaji estimates that 15 percent of Darayya’s residents have returned to the city since it came under regime control in 2016, but there are no official statistics. The city’s pre-war population, around 255,000 according to the 2007 census, drastically decreased to around 7,000 civilians and fighters in the days before its remaining inhabitants were expelled to the northwest in 2016.

Many residents in the areas under consideration for redevelopment, including al-Khalij, are wanted by regime security forces, and are therefore “unable to raise objections within the specified time periods,” al-Khaled explained. “It is also difficult for their relatives to represent them because obtaining the necessary security approvals is unlikely or takes a long time, causing objections to be submitted late.”

Accordingly, former residents of areas subject to decrees and decisions regarding redevelopment “are denied their right to legal recourse, in a way that goes against the letter and spirit of the constitution,” al-Khaled said. They are “only allowed to file administrative objections within short specified periods outlined in the decrees, and the judiciary has been sidelined from consideration and oversight over these cases,” he added.

An arena for forgery

In the years since Damascus regained control over several previously opposition-held areas, Syrian media reports have shed light on widespread violations of property and ownership rights. These have included forging documents to take possession of properties belonging to displaced people.

In April, Syrian Investigative Reporting for Accountability Journalism (SIRAJ) published an investigation exposing Syrian security networks forging real estate records of properties owned by Syrians living outside the country, in “one of the largest real estate theft operations.”

In Darayya, residents have recently noticed a surge in real estate property violations, with “brokers working with forgers to carry out purchases and sales, especially of properties owned by displaced people,” one lawyer in the city said, requesting anonymity for security reasons.

The lawyer said he refuses to handle any real estate sale cases involving parties outside Darayya due to concerns about potentially compromising the rights of either the seller or the buyer. Such transactions also often “require security approval, leading many lawyers to decline such cases,” he added.

For victims of forgery and false sales, the options are “limited to seeking justice through the national judiciary,” which is currently unlikely given its lack of independence, the Darayya-based lawyer said.

Creating a suitable legislative environment “could allow for challenging unconstitutional laws like Law 10, asserting original ownership rights, addressing crimes related to financial assets as defined in the Syrian Penal Code and seeking restitution and compensation for the damages incurred due to property loss,” explained Hussam al-Sarhan, a lawyer and board member of the Turkey-based opposition Free Syrian Lawyers Association.

But the legal reality with regards to property in Syria is in chaos, made worse by “the burning and destruction of many real estate records and civil status departments” since 2011, Sarhan said. This, in addition to “the imposition of conditions and obstacles before property owners” contributed to “stopping the registration of sales in the real estate records in some areas, and [people]making do with undocumented sales contracts, for prices far from the true value,” he added.

With little hope of return, Muhammad is now seeking a buyer for the ruins of his house for the cheapest price possible. But “those who neglect their rights face the most damage, which is shared, in this case, by both the buyer and the seller,” lawyer al-Khaled noted. He stressed the importance of raising legal awareness among citizens about housing, land and property issues, calling on property owners to “safeguard their ownership titles, as they may be useful in the event of any political settlements addressing the rights of owners, including refugees and internally displaced people.”

*Pseudonym used for security reasons.

This report was originally published in Arabic and translated into English by Nouhaila Aguergour.