Education in Afrin’s ‘line of contact’ villages hostage to unpredictable shelling

Villages on the line of contact between regime and Turkish-backed opposition forces in the southern Afrin countryside live under constant threat of unpredictable shelling. The volatile security situation leaves families choosing between sending their children to school, despite the risks, or depriving them of an education in the hopes of keeping them safe.

15 December 2023

On the days she can, Hanifa Hassan, 31, sends her two sons to school in their village in the south Afrin countryside, two kilometers away from positions held by Turkish and Ankara-backed opposition factions. Her youngest is in the first grade, his older brother in the third. From the moment they leave until they return, she worries, “fearing that shelling could happen at any moment.”

Some of those worry-filled days, while Hassan waits, her fears are realized when she hears the booms and bangs of shells and gunfire. She runs to her son’s school in al-Dhuq al-Kabir, a regime-held village in the Sherawa subdistrict of Afrin in Syria’s northern Aleppo countryside, and brings them home.

Hassan and her children remain tense for days afterward. She delays sending them back to school, and if the sound of bombardment comes at night, her children “refuse to go to school the next day,” she told Syria Direct, recalling one recent incident on December 9.

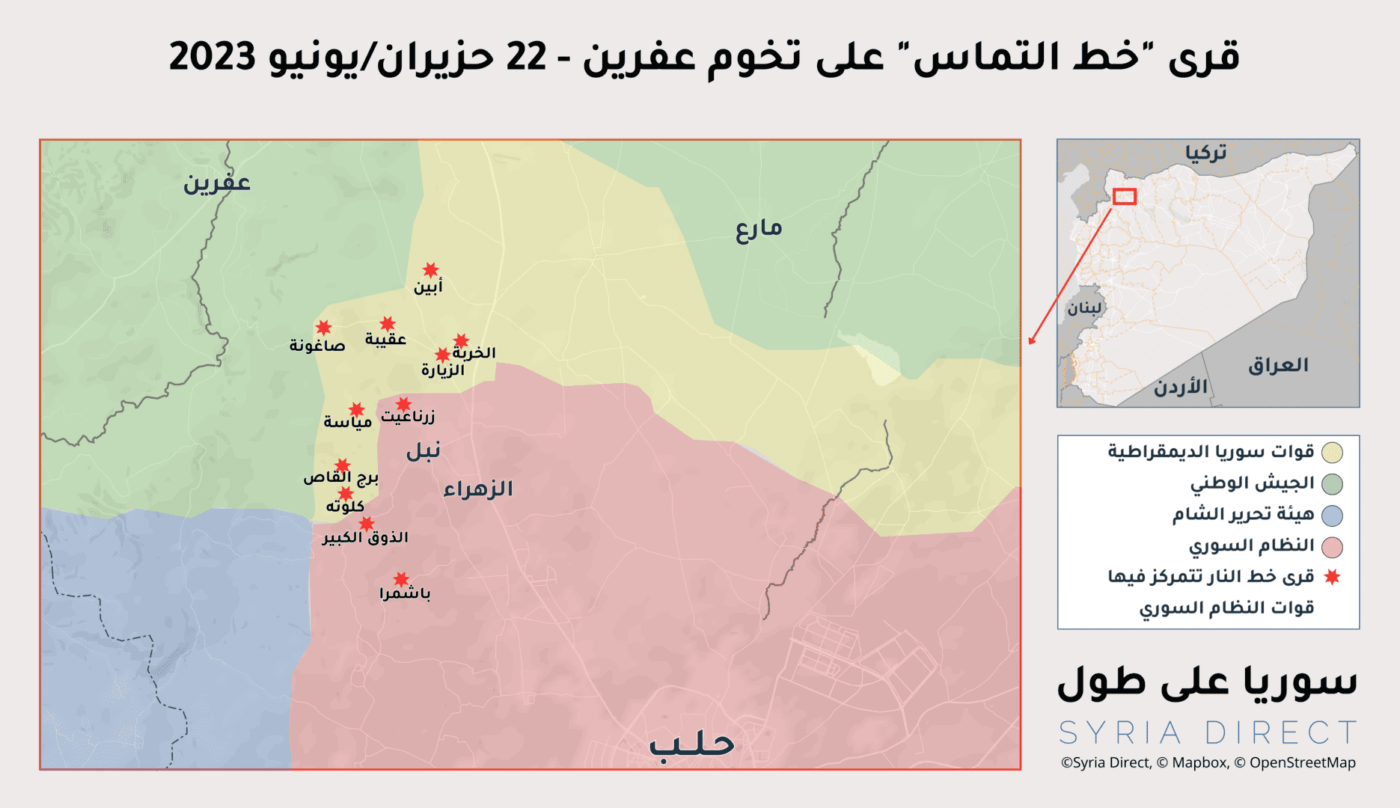

The villages in Sherawa are scattered along a line where territory held by Syrian regime forces meets that held by the Turkish forces and the Ankara-backed opposition Syrian National Army (SNA).

In 2018, the SNA took control of most of the Afrin region of Syria’s northwestern Aleppo province from the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG) with Turkey’s support during Ankara’s “Operation Olive Branch.” The YPG withdrew from Afrin’s southern Sherawa subdistrict, and regime forces moved in to take their place.

The Sherawa villages are now militarily controlled by Damascus, while they lie within the areas of influence of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), of which the YPG are a main component.

These villages—al-Dhuq al-Kabir (also known as Kundat Mazen), where Hassan lives, alongside Sughana (also known as al-Basliya, Aqiba, al-Ziyara, al-Khirba, Burj al-Qas, Bina (also known as Abin), Kalouta, Bashmara, Zarnait and Mayasa—have become a line of contact.

As such, they are periodically shelled by opposition and Turkish forces. Attacks in recent years have killed and injured civilians, including school-aged children. Many homes have been destroyed and agricultural lands burned. Schools, too, have been damaged.

The bombardment is unpredictable, and Sherawa’s volatile security situation pushes residents to stay close to home. Families with school-aged children must then choose the lesser of two evils: send them to school, despite fears they could be injured while away from home, or keep them home, depriving them of an education in the hopes of protecting them.

Education in the crosshairs

In the “contact line” Sherawa villages, and in the neighboring Shiite-majority towns of Nubl and Zahraa, controlled by regime forces and affiliated Iranian militias, education is held hostage to fluctuations in the military situation.

Schools temporarily close during periods of shelling, leaving students without an education for days, and sometimes weeks. The scenario repeats itself, again and again, throughout the school year, teachers and students in the Sherawa villages told Syria Direct.

Some 1,722 students attend school in the villages along the line of contact in the southern Afrin countryside, taught by 148 teachers, Noura Abdo, an official with the local administration that oversees education in the area, told Syria Direct. Sherawa’s schools adopt the curriculum of the SDF-backed Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES).

Afrin villages on the line of contact between regime forces and Turkish-backed opposition forces in the Sherawa subdistrict south of Afrin, 23/6/2023 (Syria Direct)

During the current school year, which began in September 2023, the days some of the area’s schools have been shut down add up to a month. Others have been closed for around two weeks, and others for 10 days. “The bombardment varies from village to village,” Abdo explained.

Over the course of the 2022-2023 school year, Sherawa schools closed their doors for more than 22 days due to shelling, according to official figures. Others were likely shut down longer, Abdo added, noting that “the administration of each school has the right to decide to close the school based on the bombing situation, so it is not possible to precisely determine the number of lost days of education.”

One of those days came this past October, when heavy shelling hit the area of al-Dhuq al-Kabir during school areas for the village’s 250 students and 16 teachers. It was a “horrifying and frightening” day, Zulukh Sido, 37, who teaches sixth grade at the school, recalled. “The sound was intense, and when the students heard it, they began to scream.” When the explosions were heard, “parents rushed to the school to take their children home, and we ran to our own homes,” Sido said.

The day after the shelling, only four students out of 250 came to school. Two days later, 11-15 out of every 40 students came to each class. Others returned gradually over the following days, teachers told Syria Direct.

Since the current school year began, al-Dhuq al-Kabir’s school has closed its doors for a total of more than eight days due to bombardment. Each time, students stay home for between three days and a week after classes resume, “for fear of renewed bombardment,” Sido said.

On the night of December 9, while Syria Direct was speaking with the families of students in al-Dhuq al-Kabir about the impact of the bombardment on their children’s education and safety, the sound of shelling could be heard in the background of WhatsApp voice messages sent by residents. They believed the shells were falling on the nearby town of Nubl, in the Aleppo countryside.

Based on the sounds of the shelling, Leila Hassan, 33, who was speaking to Syria Direct at 10:30pm when the bombardment took place, decided that she would not send her children to school the following day. “This is our situation,” she said. “It’s awful. We don’t know what to do.”

The next day, Munira Ali, a teacher at the village of Bashmara, south of al-Dhuq al-Kabir and also on the line of contact, said only 40 out of 105 students attended class due to the shelling. Her school has closed its doors for 15 days so far this school year, she told Syria Direct. “Education continuing depends on the bombardment stopping,” Ali added.

Read more: Turkish-backed opposition shelling keeps ‘a people of olives’ from their land in Afrin

Children victims of bombing

In Kalouta, a village north of al-Dhuq al-Kabir, Zainab Hussein Ibrahim, 14, was killed and her brother Bakr, 11, was injured on June 4, 2021 when Turkish bombardment struck their home. The incident took place the same day the United Nations marked its yearly International Day of Innocent Children Victims of Aggression.

The year before, three members of a single family were killed in Aqiba, north of Kalouta, when the village was struck by shells fired from positions of Turkish and Turkish-backed Syrian opposition factions on February 25, 2020. The roof of the family’s home collapsed on them.

In the wake of repeated shelling, the AANES-affiliated Afrin Region Education Authority, which oversees the Sherawa villages’ schools as well as schools in the northern Aleppo countryside that serve people displaced from Afrin, decided to shut down the school in one Sherawa village—Sughana—around four years ago. The body was concerned for the lives of the schoolchildren, given Sughana’s proximity to Turkish positions and areas of influence of Ankara-backed factions.

Since the school closed, students have been forced to attend schools in neighboring villages, which are also in the crosshairs of Turkey and the factions it backs.

Beyond the risk that shelling could claim students’ lives, persistent danger impacts their mental health. Students are tense, unbalanced, teachers said. They lose concentration in class, focused instead on the shelling and its fallout.

When panicked by shelling, “students often leave the school for home, leaving their bookbags behind them, and come back the next day looking for them,” Sido said.

As a result, the poor security situation in the Sherawa villages leads to “a fall in the level of education, delaying the completion of school courses during the academic year,” Nirouz Ahmad, 27, said. Ahmad teaches with Sido at the al-Dhuq al-Kabir school.

But worse than the educational impact, in her opinion, is to sense “the psychological impacts on the children—their reactions when shells fall,” she said.

Damaged schools

One year ago, shrapnel fell in the courtyard of the al-Dhuq al-Kabir school, breaking windows while students were in class, though none were injured, education official Abdo said.

A shell also penetrated the wall of the high school in Bina village, also in the Sherawa area, two years ago. Fortunately, the incident took place “in the early morning, before children arrived at school,” Abdo said. She noted there have been repeated similar incidents, including in 2019 at the Bashmara village school, where bullets and shell fragments falling nearby left holes in the school’s walls.

Holes in the walls of the Bashmara village school in the Sherawa subdistrict of Afrin, left by bullets and shrapnel from shells fired from areas held by Ankara-backed opposition factions, 10/12/2023 (Syria Direct)

The village of Burj al-Qas between Kalouta and al-Dhuq al-Kabir, has not been bombarded by Ankara or the factions it supports. But its close proximity to Turkish positions, one kilometer away, puts it in constant danger, the principal of the village school, which has 120 elementary students and 230 middle and high school students, said.

“When you hear the sound of shelling, your main thought is to ensure nothing happens to any of the students,” Fatima Ali, 20, a third-grade teacher at the Burj al-Qas school, said. This past October, when there was bombardment near the village, she recalled the screaming and crying of children, and how she was “powerless to do anything.”

Ali tried to “calm the students, approach them and convince them that the shelling was concentrated on far-off places,” she told Syria Direct. When the shelling stopped for a few minutes, the school sent students home and closed for the day. Just then, “the shelling started up again, at a more violent pace.”

The village’s elementary school has shut down for a combined total of more than two weeks since the start of this school year due to the exchange of shelling, she noted.

Teachers and administrators’ fear of schools being targeted has reached the point of refusing to provide any information about the issue. The administration of a school in one of the villages Syria Direct contacted refused to make any statement, for fear that “talking about the educational process and our school could make us a direct target for bombardment.”

When night falls over al-Dhuq al-Kabir to the sound of shells in the distance, rather than telling bedtime stories, Hassan tries to “calm my children in vain,” she said. Despite her best efforts, “they go to sleep afraid, and refuse to go to school the next day, for fear of the bombing.”

This report was originally published in Arabic and translated into English by Mateo Nelson.