HTS looks to Idlib’s Christians and Druze to whitewash violations (map)

After years of violations, HTS aims to adopt a new policy of openness towards Idlib’s minorities, returning some seized properties and encouraging Christians and Druze to return. Still, discrimination persists and the hardline group has not compensated property owners for years of losses.

11 December 2023

PARIS, IDLIB — The land, 60 dunums in al-Judayda, a Christian village in Syria’s northwestern Idlib province, was everything to Julian’s family. From season to season, it sustained them, until Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), the hardline opposition group that reigns in Idlib, confiscated it five years ago. In October, the family finally got it back.

Julian (a pseudonym) fled with his wife and six children from al-Judayda to regime-controlled Aleppo city in 2015, fleeing regime bombardment of opposition-held Idlib. His parents refused to leave—they wanted to hold on to the family’s home and land.

For three years, they did. But when Julian’s father died in 2018, HTS fighters barred his mother from accessing her land, “under the pretext that her mahram [close male family member] had died, and the land now belonged to the mujahideen,” he said. They also “seized some of the furniture, and bought a tractor for dirt cheap,” he added.

In the years that followed, Julian’s mother petitioned HTS commanders time and again to return her land, the family’s sole livelihood. In 2021, she recovered 15 dunums, while “most of it, which contains fruit trees, remained in HTS hands until this past October,” Julian said.

HTS returned the land to Julian’s family as part of a process it began this past September, returning real estate seized as “spoils of war” from Christians and Druze in the parts of northwestern Syria it controls.

After years of documented violations against minorities, HTS and its civil face—the Syrian Salvation Government (SSG)—is adopting a different policy towards minorities in its territory. Returning seized properties to their rightful owners is part of efforts the group began in 2020 to remove its name from international terror lists by changing its behavior and showing greater openness to the West and the local community—particularly religious and ethnic minorities.

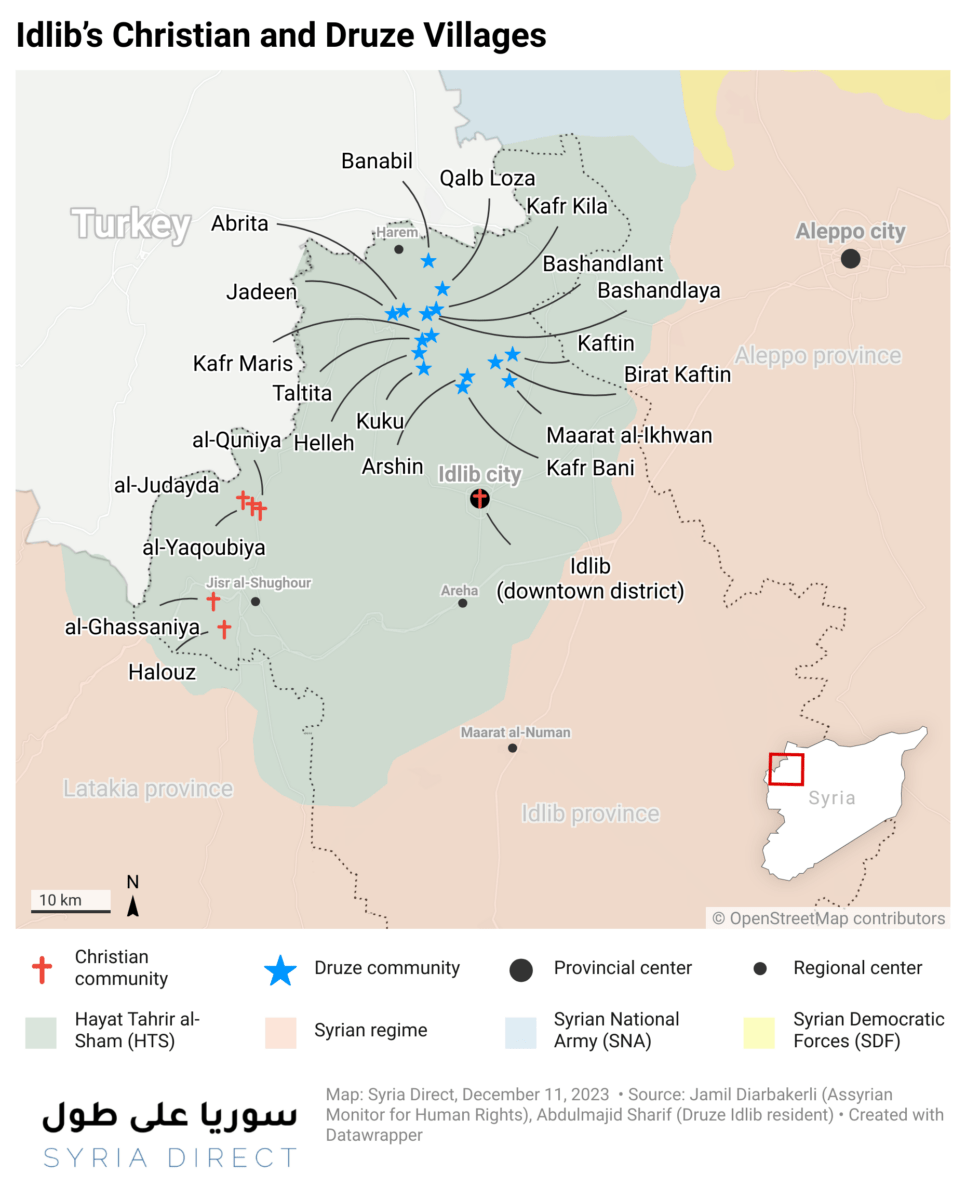

A map shows the location of some of Idlib province’s Christian and Druze villages and communities (Syria Direct)

In 2010, Idlib province was home to an estimated 10,000 Christians. Today, roughly 300 people remain in villages and towns in the Jisr al-Shughour countryside, including al-Yaqoubiya, al-Judayda, al-Quniya, al-Ghassaniya and Halouz. Downtown Idlib city also contains a number of Christian properties.

The number of Druze in the province, meanwhile, has fallen from around 30,000 before 2011 to roughly 12,000 today, Abdulmajid Sharif, a member of Idlib’s Druze community, told Syria Direct. Most live in 18 villages in the Jabal al-Sumaq area near the town of Harem, two of which were mixed Sunni-Druze communities before the March 2011 revolution.

After the Victory Army—an alliance of opposition Islamist groups led by HTS, then known as the Al-Qaeda affiliate Jabhat al-Nusra—took control of the area in 2015, all Druze villages became mixed. Today, they are home to some original Druze residents as well as a Sunni population that includes both Syrians and non-Syrians.

Today, HTS policy aims at ending years of violations against Idlib’s minorities and encouraging those who fled to return. But can the group turn the page on years of oppression and violations? Will it compensate Idlib’s Druze and Christians for the difficult years they experienced? And as it returns properties, will the owners have the right to dispose of and manage them as they wish, without interference?

A new leaf

Since HTS—then Jabhat al-Nusra—took control of the area in 2015, it has repeatedly violated the rights of Idlib’s Christians and Druze, including confiscating absentees’ properties and imposing restrictions on those who remain. These laws and restrictions have included barring them from practicing their religious rituals.

In June 2015, 20 Druze were reportedly killed in the Jabal al-Zawiya village of Qalb Loza when a Tunisian Jabhat al-Nusra commander attempted to seize a civilian home in the village. When the owners resisted, the commander and his men opened fire on civilians who had gathered.

Al-Yaqoubiya, a Christian village in the countryside of Jisr al-Shughour, in the west of Syria’s Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS)-controlled Idlib province, 25/11/2023 (Bahaa Taha/Syria Direct)

Christians who remained in HTS territory were generally allowed to work their farmland, while subject to severe restrictions and limitations on their freedoms. Some land was confiscated. The same was true of the Druze, who suffered an additional condition of being forced to “embrace Islam.”

Seeking to turn the page on this past, HTS in September began to hand over most Christian homes it confiscated to their owners, their authorized representatives or local community leaders authorized to manage the process, Christian sources in Idlib told Syria Direct.

Abu Boutros (a pseudonym), one of the Idlib Christians authorized to follow up on Christian real estate issues with HTS, confirmed that “HTS handed over most real estate—houses and shops—with the exception of a very small portion, though they are on the way to a solution.” Syria Direct attempted to learn why the return of some properties was delayed, but Abu Boutros declined to explain.

Abu Boutros called on Christians living outside Idlib who have not recovered their property rights to appoint people in the area to do so. “Since Christian community leaders received the properties, they have become authorized to collect rents from the occupants, whereas HTS used to collect these rents,” he said. Tenants living in some of the returned properties “will be evicted at the start of 2024,” he added.

HTS has not followed the same policy with Idlib’s Druze. Druze real estate was only returned to first-degree relatives living in the area. Otherwise, “their properties remained under HTS guardianship,” Sharif, who lives in Idlib, told Syria Direct. He was not able to take ownership of a house belonging to his brother, who died before the process to return real estate began, because HTS does not consider him a first-degree relative.

The condition of returning property rights only to the owner or first-degree relatives did not apply to Christians, with the exception of farmland, Abu Boutros said. Druze farmland, meanwhile, is not being returned at all, Sharif explained.

“How is farmland different from residential real estate, for HTS to prevent its return?” Sharif wondered. His nephew, his brother’s son, has been “demanding his father’s land for seven years, and has not been able to recover it until now,” despite HTS’ professed policy shift towards minorities.

In a condition not applied to Christians, HTS requires Druze to “keep the families occupying their properties for a full year after they are returned, in exchange for a fair rent,” Sharif said. “If the tenant does not pay, the property owner can refer to an HTS-affiliated office to compel them to do so,” he added.

Syria Direct reached out to HTS and the Salvation Government to clarify the reason for discrimination between Christian and Druze property owners, as well as between residential and commercial properties and farmland, but did not receive a response by the time of publication.

Incomplete rights

For years, while the fruits of Julian’s family’s land went to HTS forces, he went through the hardest years of his life displaced in Aleppo city. “While I’m working day and night to provide food for my children, and paying high rents in displacement, there are those plundering our livelihood and usurping our property in al-Judayda,” he said.

“Our income was seasonal. In the winter, we pressed oil from the olives and lived on the profits for several months. In the summer, we benefited from fruits and vegetables,” Julian said. Today, he is “helpless to secure a little olive oil.”

Although HTS returned the family’s land in full in October, Julian’s family did not fully recover its rights, as he sees it. The faction “did not pay compensation for the years it profited from [the land], and did not hold those responsible for these crimes accountable,” he said.

The same is true for Abu Tareq, 67, a Druze from Idlib who has lived in Lebanon since 2015. In September, HTS returned his house and two businesses to his sister, after she submitted an authorization form and video recording he provided confirming he wanted her to receive the properties. But the faction “did not return the house’s furniture or the shops’ equipment, or pay compensation for them. The damages of the past years were also not compensated,” he told Syria Direct.

Abu Tareq left his native village of Kaftin, in the northwestern Idlib countryside, with his wife and son on a family visit to Lebanon in 2015. Days after he left, HTS seized his properties, “as though they were waiting for us to leave,” he said.

He tried to get his properties back through members of his family at the time, but “HTS refused to return it, so I chose to stay in Lebanon,” he recalled. All the years since, Abu Tareq has suffered “a very hard life,” as he put it. He relies on aid, as “my wife and I cannot work because of our age,” while his son has an intellectual disability and cannot work.

With HTS’ apparent about-face and openness towards Christians, Julian—who has been longing for his mother and suffering great hardship in displacement—tried to go home to al-Judayda in recent months. He submitted a request to HTS through acquaintances in the village, but was not approved. “There is a red line against me,” Julian said. He believes he is wanted by HTS.

Staying in Aleppo costs Julian 40 million Syrian pounds per year (approximately $2,900 according to the current black market exchange rate of SYP 13,800 to the dollar) in “rent for a house and shop, as well as electricity and water bills,” he said.

“If they assured our safety, no Christian would remain displaced from his village in Idlib,” Julian said. He is not happy in Aleppo. “One breath in al-Judayda is better than 600 in Aleppo,” he added.

Some have been able to return. Abu Boutros noted that “some young Christian men have returned from regime-controlled areas to al-Judayda and al-Quniya villages in recent months.” He did not provide details about how many have returned, how returns are coordinated or how HTS deals with returnees upon arrival.

The market in Idlib’s Christian village of al-Quniya shows traces of destruction from bombardment in recent years, 25/11/2023 (Bahaa Taha/Syria Direct)

Demographic change

Visiting the village of al-Yaqoubiya, it is easy to pick out the faces of those who have been displaced to it, taking the place of the original population, most of whom fled HTS-controlled areas.

At the entrance of the village sit the remains of concrete houses, torn down by HTS two years ago as construction violations. They were built by displaced people on land owned by displaced Christian families, sources there told Syria Direct’s reporter, who visited a number of local villages.

The al-Quniya church school, which has become a shelter for displaced people living in the western Idlib village, 25/11/2023 (Bahaa Taha/Syria Direct)

Recent HTS decisions to return Christian homes have not impacted the return of the village’s original residents. Rather, the displaced people in al-Yaqoubiya now pay rent to the owners of the properties or their representatives, rather than HTS as in previous years. Rents are still cheap, Syria Direct’s reporter learned from displaced people there.

There are currently 28-35 Christian families in al-Yaqoubiya, each made up of one or two elderly people. In neighboring al-Quniya, where the village’s church school has become a shelter for displaced people, around 92 Christian families remain. In al-Judayda, Julian’s hometown, there are around 85 original families. The villages of al-Ghassaniya and Halouz, meanwhile, have been completely empty of Christians since 2016, after all the residents fled. These figures are estimates Syria Direct heard from sources in these villages.

Jamil Diarbakerli, director of the Sweden-based Assyrian Monitor for Human Rights, which focuses on Christian issues in the Middle East, estimated “around 300 Christians remain in Idlib, while Idlib city is completely empty.” There are no precise figures due to “the difficulty of conducting a periodic survey in the area, given restrictions on human rights institutions,” he added.

“This part [of society] has all but ceased to exist in the area, after it was once an active presence in more than one village and town,” Diarbakerli said. He described what the region has witnessed as “demographic change operations.”

“When you plant one group in an area at the expense of another, at the expense of the existence, presence and proportion of the original group, that is where the biggest problem lies,” he added.

The same changes have affected Idlib’s Druze, although to a lesser extent. Eight years ago, the province’s 18 Druze villages transformed from single-sect villages to a mixture of local residents and displaced people who came seeking shelter, Sharif said.

“All the Druze villages are now mixed between displaced people and the Druze,” Sharif added. “This does not bother us. Rather, the problem is in houses being occupied by the families of foreign HTS fighters. These were recently vacated and handed over to Syrian families, not the owners.”

Housing displaced people in Druze villages does mean a change in their demographic makeup. Abu Laith (57), who lives in the village of Kaftin, is not worried about this shift, so long as “the displaced people do not change the structure of the property and its ownership,” he said.

“We are in a state of war. People are looking for shelter, and it is natural for people to move from village to village, regardless of the identity of the original inhabitants,” Abu Laith added. “Our problem is not with those living in our villages, but with HTS, which confiscates our homes and land.”

The al-Yaqoubiya village church, part of which was destroyed by the February 6 earthquake that struck Turkey and Syria, 25/11/2023 (Bahaa Taha/Syria Direct)

Return to Idlib

Despite the risks and unknown future that returning to Idlib entails, Julian wants to go home to al-Judayda. It is not fear that stops him, but HTS that “still refuses my return.”

Julian’s experience contradicts recent HTS policy, aimed at using minorities to demonstrate openness and encouraging them—especially Christians—to return to their villages in HTS-controlled areas.

HTS commander Abu Muhammad al-Jolani visited Idlib’s Christian and Druze villages repeatedly over the past three years, and met with community members. During these meetings, al-Jolani asked Druze and Christians to urge their displaced relatives and loved ones to return to Idlib. He pledged that HTS would ensure their protection and restore their rights, four Christian and Druze sources told Syria Direct.

Diarbakerli, of the Assyrian Observatory, confirmed the existence of “efforts and discussions between Christian figures and HTS” in the context of addressing past violations. But “until now, HTS cannot control the rampant weapons in the area or its members,” he said. “How can we be sure of the procedures for addressing violations? If any violation occurs, HTS will respond that the ones responsible for it are an unruly, undisciplined group.”

Most Christian returns to Idlib province are being coordinated “through the priest of al-Yaqoubiya, who liaises between HTS and Christians who wish to return home,” Syria Direct learned from sources close to HTS. The faction reportedly conducts a security check on those wishing to return, and if no issue is flagged, allows them to do so.

Apart from the question of Christians trusting HTS, or the extent to which it will honor the promises it has made, a lack of basic services such as electricity and water in Christian villages, compared to other parts of Idlib, is another factor preventing their return, Syria Direct learned.

Commenting on that, Abu Boutros said HTS has promised to “improve the electricity and water situation in our villages before the end of the year.”

Bassam al-Ahmad, director of Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ), a human rights organization that documents violations in Syria, downplayed the chances of HTS’ new approach succeeding. Likening it to past efforts by Afghanistan’s Taliban, he said it is not likely to succeed for reasons related to the moderate ideology of Syrian society.

“HTS is trying to send reassuring messages to minorities with help from international organizations and Gulf countries,” al-Ahmad said. He described its efforts as “an unsuccessful investment, dressing up something ugly. HTS’ project, in essence, is not based on citizenship, but rather views those people as second class, or dhimmis.”

Article 17 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights holds that “everyone has the right to own property alone as well as in association with others. No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his property.” Al-Ahmad linked this right to “a person living a safe and dignified life,” which is not currently available to minorities in Idlib.

Under Article 768 of the Syrian Civil Code, a property owner has the sole right “within the limits of the law” to use, exploit or dispose of property. Despite returning properties to Christians, HTS does not allow owners to sell or transfer their belongings. “The HTS decision to bar Christians or their relatives in Idlib from disposing of their properties violates the letter and spirit of the law, regarding an owner’s right to dispose of property as they wish,” one Syrian lawyer living in Afrin told Syria Direct, speaking on condition of anonymity.

Article 15 of the 2012 Syrian Constitution also stresses that “private ownership shall be protected, and private property cannot be removed except in the public interest by a decree and in exchange for fair compensation,” the lawyer added. “Private property may not be confiscated, except for necessities of war and public disasters, and [the Article] also stipulates the existence of a law for fair compensation.”

Under international law, the seizure of property is considered a war crime, as “the four Geneva Conventions of 1949 protected non-combatants, barred the seizure of their property and called for measures to be taken to prevent all violations,” the lawyer added. Article 8 of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court also “classified the appropriation of property during armed conflicts, whether international or non-international in nature—as in the case of Syria—as a war crime, especially when committed as part of a plan, policy or large-scale commission” of such acts, he added.

“International laws at all times protect property, whether from appropriation, looting, partial destruction, reprisals, etcetera,” al-Ahmad said. In the case of Idlib’s Christians and Druze, what happened “is a war crime—wide-scale, systematic violations have taken place,” he added. “We are talking about thousands of people.” These violations “may amount to crimes against humanity.”

“The perpetrators must be held accountable,” al-Ahmad concluded. “People must be compensated, and their property must be returned. This is a general Syrian problem, one that has been repeated in other areas, such as Afrin, eastern Syria, Daraa, Douma and beyond.”

**

This report was originally published in Arabic and translated into English by Mateo Nelson.