Northeastern Syria marks two years of legal paralysis as de facto authorities struggle to issue new land registry

In northeastern Syria, the lack of an accurate land registry prompted de facto authorities to suspend most ongoing court cases regarding property rights. Two years later, legal paralysis prevails.

30 January 2023

QAMISHLI — Imagine a place where land cannot be bought or sold legally, where real estate markets are paralyzed and legal disputes frozen. A place where rightful owners are locked out of their own houses for years and legal documents can become meaningless overnight.

This is the situation today in parts of Syria controlled by the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES), a de facto alternative government founded in 2013 by a Kurdish-led coalition of Kurdish, Arab, Assyrian and Syriac political parties. In those territories, there is no AANES-managed cadaster—an official register documenting the size, location, and ownership of all properties. The result is near-total legal paralysis.

Syria has an official land registry, a mammoth register of maps and documents born of an uneasy marriage between centuries of Ottoman rule and decades of French colonial law. But it is run from Damascus by the General Directorate of Cadastral Affairs, an organ of the Syrian government, and not by the AANES, which lacks its own means to record property transfers.

On January 28, 2021, the AANES issued Decision 6 of 2021 barring its courts from ruling on land ownership disputes until a new registry could be created. Decision 6 also restored ownership of certain properties to their pre-2012 status, and suspended most ongoing legal cases over property rights.

Two years later, Decision 6 continues to disrupt northeastern Syrians’ access to property rights and their ability to secure legal documents, without an alternative cadaster in sight.

AANES officials say the decree was a necessary evil that has caused temporary harm but will secure everyone’s rights in the long run. But in a region with a long history of politically motivated land seizures and forced evictions, many worry that a new land registry will not set the record straight.

A tale of two legal systems

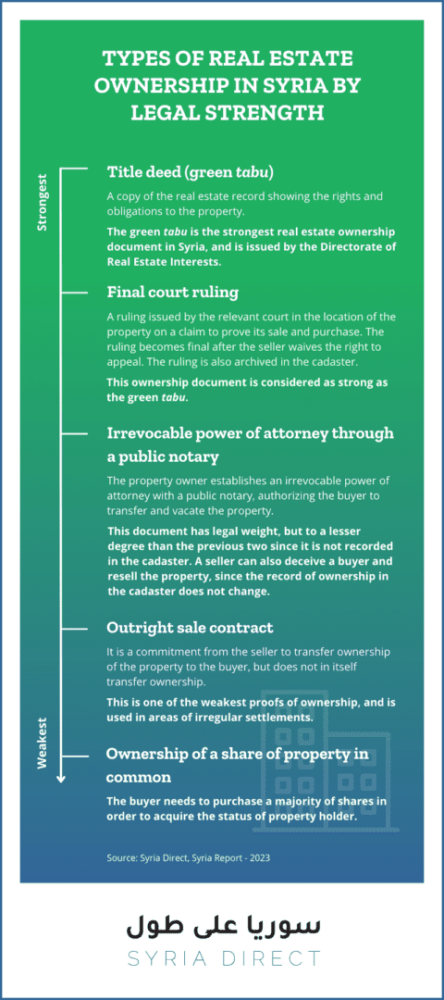

Infographic | Types of Real Estate Ownership in Syria by Legal Strength (Syria Direct)

When Decision 6 was issued a little over two years ago, lawsuits over ownership were piling up in the AANES courts due to rampant legal confusion surrounding property rights.

“When the AANES’ alternative judicial system was set up in 2013, some people saw an opening,” one AANES judge told Syria Direct on condition of anonymity as he is not allowed to speak to the media. “People started flocking to the courts with forged documents to get their transactions approved by judges. People who had emigrated during the war would meanwhile return to Syria and find that their properties had illegally been sold to others.”

This legal chaos stemmed partly from the war and from judges’ limited means to verify the evidence presented in court. It was compounded by the existence of two competing legal systems in northeastern Syria, each of which issued its own legal documents.

The older system was that of the Syrian government, which administered all regions of the country before 2011. Even after losing territorial control over most of northeast Syria, Damascus has retained an administrative presence there throughout the war, and continued to operate courts, schools and civil registry offices.

At the same time, starting in 2013, the AANES developed its own public administration network, passing its own laws and decrees and creating courts to implement them. But this overlapping legal setup quickly spiraled out of control as people started filing cases in one court or the other—and sometimes in both at once—seeking a favorable ruling. This often led to conflicting rulings issued at the same time by different courts.

The Syrian government’s court of justice is located in a Damascus-controlled part of Qamishli, northern Hasakah province, 24/01/2023 (Solin Muhammed Amin/Syria Direct)

Proving ownership

In cases pertaining to property rights, this legal situation was particularly unstable because AANES judges remained highly dependent on decisions issued by Damascus-run administrative bodies.

“In Syrian law, there are different types of documents proving ownership, with different legal value,” Izzedin Saleh, the executive director of Synergy Association for Victims, a local organization providing legal support to victims of human rights and housing, land and property (HLP) rights violations, told Syria Direct.

The strongest proof of ownership in Syria is the green tabu, a certificate of registration issued by the cadastral services. Court decisions certifying the ownership of a property serve a similar function, and are also filed in the cadaster. There are also legal documents with less legal value, such as ownership registered by power of attorney granted to a public notary. The documents with the lowest legal weight are outright sale contracts, which are considered one of the weakest proofs of ownership.

Cadastral registration is therefore the most powerful legal tool to record property transactions, clearly overriding other types of legal documents, including judicial decisions issued by AANES judges. But since the official cadaster is managed in Damascus, only the regime can amend it. And without its own registry, the AANES’ attempt to create an independent, alternative legal system is being built on shifting sands.

“Without a real estate registry, we cannot protect the property rights of citizens,” Attia al-Naama, a member of the Social Justice Council, the AANES’ supreme judicial authority, told Syria Direct. “We issued Decision 6 in order to preserve all rights to private property and avert abuses until the establishment of a real estate registry that parallels the Syrian state records.”

A Syrian army checkpoint guards the entrance of a regime-controlled neighborhood in Qamishli, northeastern Syria, where several administrative bodies belonging to the Damascus government still operate, 24/01/2023 (Lyse Mauvais/Syria Direct)

A fraught history

When Decision 6 was announced, some legal experts within the AANES expected a new cadaster would be available in a matter of months. But two years later, the AANES’ Executive Council tasked with issuing a new cadaster has yet to complete the task. In the meantime, real estate court cases are suspended with a few exceptions, including criminal lawsuits for usurpation of property, mortgage and lease contracts, rental disputes and inheritance cases.

“Decision 6 was meant to protect people’s rights, but it also froze everything in place,” the AANES judge said regretfully. “Some people have been waiting for a court decision on their property for two years now.” Part of this delay is because the Syrian government’s cadaster, which should serve as a starting point, is itself a flawed record derived from decades of discriminatory real estate policies.

“Property rights were poorly recorded before the war, and violations of housing, land and property rights were already a huge issue,” Saleh said. “Many transactions took place outside the formal legal system and were never registered on the cadaster because legal procedures were long and complicated under the Syrian regime, and inaccessible to some communities.”

Areas of northeastern Syria that border Turkey, which were historically populated by Kurds and other ethnic minorities—such as Syriacs, Assyrians and Armenians—faced a particularly restrictive property regime. In rural areas located outside zoning plans, any real estate transfers had to be approved by state security services, which severely restricted some minorities’ access to land. “These restrictive laws implemented in frontier areas under the pretext of security were politically motivated,” Saleh added. “In 90 percent of cases, Kurds didn’t get approval from the security services to buy land.”

As a result, some people used alternative means to record transactions among themselves and circumvented the official land registry, which became highly unreliable. “If you take Qamishli’s cadaster today and walk around the city, you won’t find more than ten houses registered under the right owner’s names,” the AANES judge joked.

Another factor stalling the adoption of an alternative land registry is the sensitive political context in northeastern Syria, fraught with tensions between communities resulting from the region’s complex history.

Hasakah province, which borders Turkey, has long been home to ethnic and religious minorities that did not fit easily into the Baathist regime’s plans for a homogeneous, Arab Syria. These groups historically had little say over the policies of the central government, particularly the distribution of land. From the 1960s onwards, discriminatory decrees were used time and again to deprive them of essential rights to citizenship and property.

In 1962, the Syrian government conducted an express census across Hasakah province over the course of a few days that stripped thousands of Kurds of their citizenship and property rights. Building on this blow, in 1974, the state seized around 300,000 hectares of agricultural land from Kurds in northern Hasakah province. These were given to Arab communities as compensation for the loss of their own lands following the construction of Tabqa Dam and Assad Lake in Raqqa province.

These farmers, who became known as the “flood farmers,” were resettled in Hasakah to create an “Arab Belt” countering the demographic weight of the Kurdish community in northern Syria. The land they received has a special status in Syrian law: amiri ownership. Amiri lands are loaned permanently by the state to private owners, but can only be transferred or sold with the approval of the state, which remains the final owner.

The amiri lands granted to “flood farmers” differ from other forms of amiri ownership in Syria, as Decree 49 of 2008 made any real estate transactions on these lands subject to approval by the state security services.

One of the provisions of Decision 6 referred specifically to the status of amiri land, as it reverted the ownership and usage rights of that land back to its pre-2012 status. In doing so, some observers claim, the AANES likely intended to quell fears among amiri landowners that their land would be seized by the new Kurdish-dominated local authorities, and to prevent them from selling their land rights en masse to unknown investors.

Decision 6 temporarily preserved the status quo on this issue, freezing political debates about the potential redistribution of the land. But inevitably, once a new registry is created transfers of amiri land in the AANES system will resume, reigniting political debates over redistribution or compensation for dispossessed owners.

Legal paralysis

Until a parallel land registry is created, residents have no other option than to try to register property transactions in regime courts, with no guarantee they will be recognized by the AANES in the future. For some communities, rights advocate Saleh said, this means once again facing discrimination in government courts and daunting security checks.

“People still need approval from the regime’s security services to register property under their name if this land is located in rural areas along the Turkish border,” Saleh said. “And to this day, Kurds and Yazidis still consistently fail to get these approvals.”

Those opposed to the regime, who are wanted for interrogation or have not completed their mandatory military service, also avoid going to regime courts where they could be arrested. To secure their property rights, those who can afford to rely on lawyers rather than attend in person.

The Syria Report, a specialized economics publication, estimated in June 2021 that lawyers typically charge SYP 250,000-300,000 ($77-$92 according to the parallel market exchange rate at the time), a sum out of reach for most, to complete a property transfer in AANES-controlled areas. Instead, some register their property under the name of another person who is not wanted by the regime, leaving them with little recourse in the event that whoever officially owns the property should choose to sell or take possession of it.

Local authorities said they are aware of the hurdles faced by residents of northeastern Syria, and stressed that they see the current paralysis as a short-term obstacle, but did not provide a clear picture of how it could be resolved.

“We know that the situation is not ideal and we considered the drawbacks as well as the benefits of Decision 6 before issuing it,” said al-Naama, the Social Justice Council member. “But it’s a temporary measure, and I do believe the benefits of protecting citizens’ rights by suspending court rulings that have no legal value outweigh the inconveniences they face today.”