Op-Ed: In Decree 3 of 2023, earthquake victims neglected and housing, land and property rights bypassed

Damascus’ Decree 3 of 2023 provides tax exemptions and loans for those whose property was damaged or destroyed by the February 6 earthquake, but does not take into account displaced property owners and rights-holders or areas outside regime control, writes lawyer Manhal Alkhaled.

30 March 2023

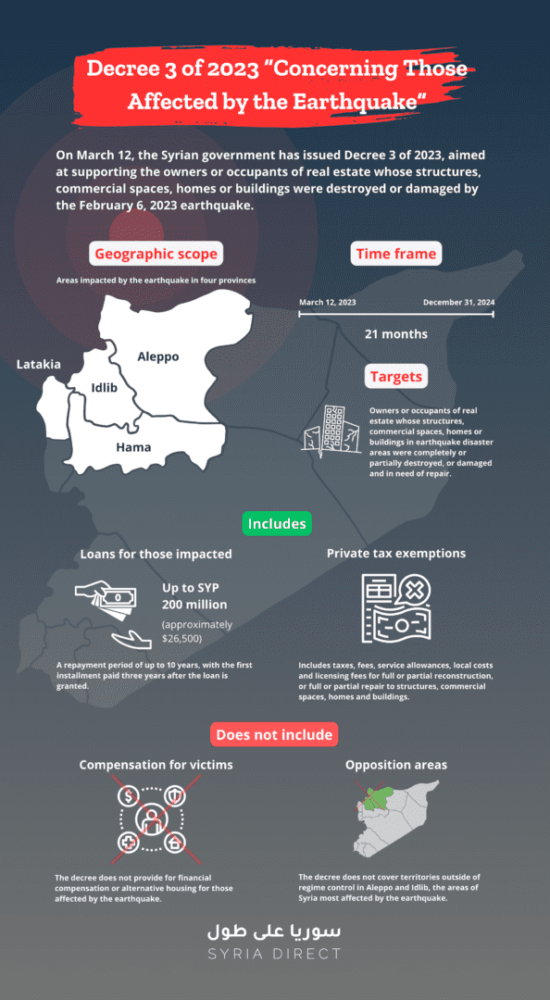

The latest episode in a series of controversial laws and decrees issued by the Syrian government over the past two decades, Decree 3 of 2023, was issued on March 12. The decree includes owners and occupants of real estate affected by the February 6 earthquake whose structures, commercial spaces, homes or buildings in impacted areas were fully or partially destroyed, or were damaged and require repairs.

Government figures and pro-government websites rushed to praise the decree after its release, describing it as “honorable,” a decree unlike any other issued since the establishment of modern Syria. It was described as one of the measures and policies related to the recovery phase “at the heart of which is support” for the earthquake’s victims, and as part of the great national plan for tackling the impact of the earthquake, which includes other measures.

It is fair to say that the decree and its provisions are not all bad. On the whole, it exempts property owners and occupants who were affected by the earthquake from all taxes, charges, local fees, service allowances, licensing fees and additional payments for total or partial reconstruction, or restoration works, for their structures, commercial spaces and homes.

The decree also grants victims the opportunity to take out loans of up to SYP 200 million (approximately $26,500 according to black market exchange rates) from public banks. These loans are repayable over 10 years, and the state will undertake to pay any loan interest and related charges, with repayments only starting three years after the loan has been issued.

Yet at the same time, reading the decree, applying its provisions to the local, legal and national context, and considering the state’s duties and responsibilities through the lens of housing, land and property rights reveals severe shortcomings in the government’s response to this disaster. This response is summed up in this inadequate decree, which shows disregard for the most basic housing, land and property requirements, as this article shall explain.

Weak disaster response

The February 6 earthquake in Turkey and Syria is classified as a “severe, rapid onset” natural disaster, a type of disaster that often impacts large cities or densely populated areas with devastating effects on communities, livelihoods and property.

According to the Syria Rapid Damage and Needs Assessment published by the World Bank on March 18, the physical damages and losses from the earthquake are estimated at $3.7 billion and $1.5 billion, respectively, bringing the total estimated impact to $5.2 billion. The losses account for reduced output in productive sectors, lost revenue and higher operating costs in the provision of services.

Responses to such disasters are often influenced by several issues, mainly related to limited resources, poor infrastructure and administrative corruption. These can be compounded by the humanitarian situation and the existence of a fragile environment dominated by conflict and crises, as is the case in Syria, where the ongoing humanitarian emergency is described as one of the largest humanitarian crises in the world.

The recent earthquake exacerbated the population’s pre-existing vulnerability to crises and natural disasters, and caused a severe deterioration in the humanitarian situation, especially in terms of food security and hazardous residential buildings. The areas affected by the earthquake were also home to roughly three million internally displaced people, representing half of all displaced people in Syria, who were already facing extremely difficult living conditions.

The distribution of areas of control within Syria between the government and three other powers—the opposition Syrian National Army (SNA) and Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) in the northwest and the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in the northeast—has further hampered relief efforts and swift access to those in need.

Therefore, the government’s weak response to the devastating earthquake was at first limited to mere statements, calls for international aid and blaming international circumstances. Eventually, it culminated in Decree 3—more than a month after the disaster. The decree came in the context of disaster management, rather than focusing on risk management, that is, a focus on preparedness, readiness and resilience-building rather than taking the approach of a reactive post-disaster response.

No alternative housing or right to housing

Decree 3 makes no mention of housing or the right to housing despite repeated domestic and international calls for the Syrian government to incorporate housing and property rights issues into the section on rights and freedoms in the Syrian Constitution and any laws and decrees issued by the Syrian head of state. International law and fundamental international conventions declare a right to adequate housing. The Syrian government is thus obliged to do everything in its power, with the resources at its disposal, to realize the right to adequate housing and take measures to this end without delay. It must also put laws and specific action plans in place to offer direct assistance, including in the form of housing or housing allowances, especially for victims of a disaster (whether natural, human-caused or a disaster with mixed causes).

However, neither successive Syrian constitutions, nor the laws and decrees based on them—including Decree 3 of 2023—have provided for the right to housing, with the right to housing being moved from the section on rights and freedoms to the section on economic principles. This is despite statements issued by members of the Damascus government in the days following the crisis that mentioned the need to secure alternative housing.* They later spoke of providing temporary housing should international support be available, going back on the national and international legal assurances made by the Syrian government.

No compensation for victims

Syria’s amended Constitution of 2012 makes no mention of the state’s responsibility to compensate victims in the event of disasters, except to shoulder “in solidarity with society, the burdens resulting from natural disasters,” as stated in Article 24.

Although Syrian law makes no reference to appropriate in-kind compensation for such situations, the state has tortious liability for any direct damage, regardless of whether it was expected. Reading Decree 3 of 2023 reveals that none of its clauses mention any financial compensation for victims of the February 6 earthquake, offer any cost-free financial allowance for repairing damaged buildings, or even pledge to pay rent allowances for those who have lost their homes. It is merely an improved version of Decree 13 of 2022, which previously granted tax relief and exemptions for properties in old city centers—including historical market areas—within Aleppo, Homs and Deir e-Zor provinces.

A discriminatory decree

Decree 3 of 2023 violates the most important principle related to the right to housing, that of “equality and non-discrimination” for all citizens entitled to support, as it only covers those affected by the February 6 earthquake. It therefore does not apply to any other natural disaster, or to Syrians affected by the military operations undertaken by government forces whose properties were partially or completely lost as a result, or otherwise left in a very poor structural state, prone to destruction at the slightest impact or natural event—such as the recent earthquake. Some of the damage to these buildings is not visible but has affected their foundations, and may only appear after some time has passed. Nor does the decree apply to areas outside government control, despite them being the most affected by the earthquake, due to government policies requiring UN aid to go through its exclusive channels.

Article 2 of the decree is clouded in ambiguity, as it stipulates that “the persons affected will be determined by the relevant governor based on the decision of a committee, formed at the decision of the Minister for Local Administration and Environment in each province, that includes the relevant authorities.”

Consequently, Article 2 follows the same pattern that the legislative authority has used in all previous decrees and laws in terms of how the persons deemed to be victims, or those covered by the privileges contained in the decrees, are determined. It gives the governor absolute power to determine who victims are according to the government’s point of view, without specifying the mechanisms and criteria to be used in determining who is entitled to these exemptions, how they can present them to the committee or their legal representation. This plunges owners of damaged real estate into a cycle of routine procedures to prove their ownership, especially those whose properties have been fully destroyed or whose documents proving their ownership have been lost or damaged.

The decree does not take into account the situation of displaced rights-holders and owners who have been displaced from their properties, some of which have been seized. It may be impossible for these people or their legal representatives to come to the committee, leaving them unable to submit the necessary requests to be covered by the decree.

Compromising on international support

The decree only covered the provinces that were most affected by the earthquake: Aleppo, Latakia, Hama and Idlib. The Syrian government declared these provinces to be “disaster areas, with the entailing effects,” four days after the February 6 earthquake.

No reason was given for the delay in declaring which areas were impacted, despite the magnitude of the disaster, the enormous losses and the need for an immediate response from the Syrian government. However, it appears to be linked to the international classification of the consequences of declaring an area to be “disaster-stricken.” This declaration grants the UN Secretary-General the right to request the application of Article 99 of the UN Charter, which states “the Secretary-General may bring to the attention of the Security Council any matter which in his opinion may threaten the maintenance of international peace and security.”

This would mean that if affected areas reached a level where they threatened international peace and security, the member states of the Security Council would have to meet and issue a resolution obliging the parties affected by the disaster to allow international relief and medical organizations to intervene and address its causes and consequences. This would contradict the Syrian government’s demands for aid to be brought in and be distributed exclusively through its channels, and would also limit the Syrian forces’ power over how the aid could be used.

No exception to the Real Estate Sales Law

The second clause of Article 11 of Decree 3 stipulates that tax exemptions and suspensions do not apply to sales tax for real estate subject to Law 15 of 2021, which is notorious for having imposed substantial taxes on the buying and selling of real estate through a “Real Estate Sales Law” based on revised valuations (current value), whereby taxes are deducted from property sales without taking into account the value agreed upon between the buyer and seller. The law is consequently unjust towards citizens and does not distinguish between ordinary citizens and realtors. It also exacerbates the housing crisis in Syria, especially for those whose homes have been damaged and who cannot afford to demolish and rebuild or secure them, and who do not have the financial means to take out the loans offered by the decree, given declining incomes and living standards. This forces them to sell their homes and search for others that can be bought at a lower price, or to rent in another area, as real estate sales in areas affected by the earthquake must remain subject to real estate sales tax.

Fears that property and housing rights are being targeted

There are concerns that Decree 3 of 2023 is part of a system of laws paving the way for an attack on real estate rights and targeting rights to property and housing in Syria as the decree opens the door to the application of Law 3 of 2018 on the removal of rubble from damaged buildings. The motives behind Law 3 remain ambiguous, but its stated purpose is to specify damaged and destroyed establishments, remove rubble, and break down the expenses and costs among those entitled to it. The administrative unit (the province, city, town or municipality) proposes an area be defined as damaged, and the province issues a decision determining the damaged real estate area or buildings.

The new decree may also be a gateway to the application of Law 10 of 2018, under which the province can demolish any real estate area regardless of whether it is damaged, simply on the basis of a decision by the governor that it should be subject to this law. Once rubble has been removed, Law 10 can be applied, establishing development zones with the aim of taking ownership of damaged buildings from their owners. This is especially true of areas of informal and unauthorized construction, where buildings fall outside development plans, are not licensed or are jointly owned, and where it is not possible for them to be recategorized as residential buildings and apartments in the real estate registry. Consequently, owners of these houses and apartments can only register them in their names at the real estate registry as equity shares. This makes it unclear who the victims are that have lost their homes due to the earthquake and should be compensated.

Conclusion

Compensation, in its modern concept, has become a responsibility that falls upon the state and society. They must both work together to protect victims, as according to the principles of administrative responsibility, compensation for damage is not just an element of responsibility, but a process of relieving the victims of that damage, especially for those affected by natural disasters.

Protecting individuals from natural and human-caused hazards and disasters is a fundamental legal and constitutional right, and the state is responsible for protecting its citizens. It is therefore imperative that the Damascus government searches for new principles and alternative ways to develop effective and sustainable mechanisms for compensating victims in order to respond to disasters and determine the rules for managing them.

*Alternative housing is a loose term that is often used to refer to housing that is built by the General Housing Establishment as part of a governmental social housing program. Recipients are required to pay for this housing. In other words, it is not free. Homeowners in informal developments may request alternative housing if their properties are seized or demolished or if the area is recategorized. However, Syrian law does not mention any right to alternative housing for people whose homes have been affected by natural disasters.

This article was originally published in Arabic.