Suffering in silence: Cancer patients in northern Syria at the mercy of the crossings

This investigation highlights how cancer patients across northern Syria are paying the price for the country’s faltering healthcare system. Cancer medications are scarce, northern Syria lacks specialized health facilities, and border crossing closures and difficulties of internal travel stand in the way of timely treatment.

1 December 2023

Muhammad Jalmoud, 18, did not know that death was waiting for him on the other side of the Bab al-Hawa border crossing when he was pleading to enter Turkey to receive treatment for cancer earlier this year, after Ankara closed its crossings with Syria in the wake of a devastating earthquake on February 6.

“My son was diagnosed with colon cancer in March 2023, after which he began chemotherapy, which was not available for free in the area,” Muhammad’s father, Taha Jalmoud, said. He estimated the cost of his son’s treatment at between $18,000 and $20,000 (between 245 million and 273 million Syrian pounds, according to the current parallel market exchange rate of SYP 13,650 pounds to the dollar).

Taha had three options: “Treat him in a private hospital in Idlib province at our own expense, or treat him in Damascus, which is impossible for fear of being arrested by the regime forces. The last option was to treat him in Turkey,” he said.

Turkey was the best option, but “the crossing’s closure hindered that, so we asked for help from [opposition-affiliated] military figures in the region,” Taha said. Through mediation by a Syrian National Army (SNA) commander in the northern Aleppo countryside, Muhammad entered Turkey on July 6, before other cancer patients were allowed to enter the country again at the end of the month. However, his brother was not allowed to enter with him as an escort, and had to “follow [Muhammad] through a smuggling route,” their father added.

Muhammad was admitted to intensive care as soon as he arrived at a specialized hospital in Turkey’s southern city of Kilis. “He did not respond to the chemotherapy because it was too late, and he died on July 16, 2023,” his father said. “He should have arrived in Turkey several months ago, and this delay led to his death.”

There are about 3,500 cancer patients in northwestern Syria, including 608 patients who were diagnosed after the February 6 earthquake. “An average of four-to-five cases are discovered daily,” Dr. Hussein Bazar, Minister of Health in the Syrian Salvation Government (SSG), said. He noted that cancer patients in SSG areas of influence in Idlib province, as well as those in areas of northern Aleppo controlled by the Syrian Interim Government (SIG), need to enter Turkey to receive treatment.

Waiting for aid

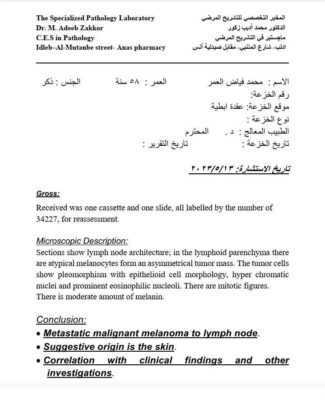

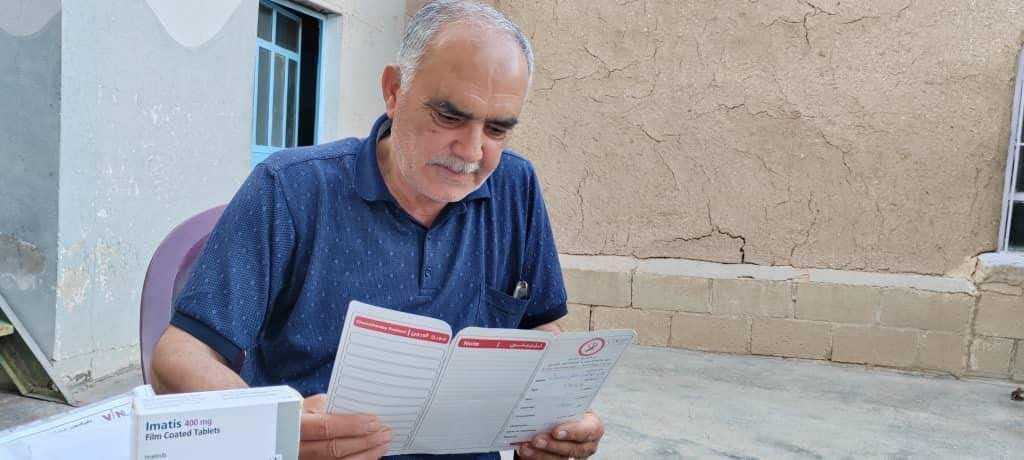

Fearing a fate like Jalmoud’s, Muhammad al-Omar, 58, a cancer patient in Idlib province, received one chemotherapy dose inside Syria “after receiving $1,200 in donations,” he said. Al-Omar is supposed to receive 24 immunological doses over the course of a year—one every two weeks—“but I have only taken one dose so far,” he added.

Several months ago, al-Omar discovered that he had third-degree skin cancer (melanoma). At the time, the Bab al-Hawa crossing with Turkey was closed.

A copy of a medical report obtained by the reporters, which explains the results of a biopsy taken from the patient, Muhammad al-Omar.

“Immunotherapy is the only treatment for Muhammad,” Dr. Ayham Jammu at Idlib Central Hospital said. “It is very expensive, and is not available for free in Syria or even in Turkey. Six doses cost $6,400 [SYP 87 million],” he added. Without aid, al-Omar cannot continue his treatment.

Nine-year-old Muhammad Sattouf is in a similar position to al-Omar. He is also looking for assistance—$8,000 to undergo a surgery in a private hospital—“after he completed 12 chemotherapy doses and 28 radiation sessions in Turkey over four years, hoping to heal and return to his school and continue his education,” his father, Haitham, said.

A copy of a “traveler’s card” issued by Bab al-Hawa border crossing for nine-year-old cancer patient Muhammad Sattouf, and his father, Haitham, as an escort.

‘I’m paralyzed’

On July 25, 2023, the opposition-affiliated administration of Bab al-Hawa border crossing announced the resumption of the entry of cancer patients into Turkey to receive treatment for the first time since the crossing closed in the wake of the February 6 earthquake—provided that patients over eight years old enter without an escort.

“I am paralyzed and helpless, and I need a companion,” said Mahmoud Fattah, 51 years old, a cancer patient residing in the city of Ariha in the Idlib countryside. He cannot sit up or carry out other activities “without assistance.” He wondered disapprovingly: “Why are they making it difficult? This is humiliating.”

“I have been bedridden for five months. They did not allow a companion with me,” Fattah added. When he pressed the authorities to allow him a companion, employees at the medical office at Bab al-Hawa crossing told him “the Turkish authorities will tear up your papers if you cannot find a person in Turkey who can help you,” he recalled.

Even if Fattah is able to find an escort in Turkey, “I cannot enter Turkey without an ambulance and a stretcher,” he added. Turkish authorities prevent Syrian ambulances from entering their territory, and cancer patients are transported exclusively by buses.

Dr. Bashir al-Ismail, the director of the medical office at the Bab al-Hawa crossing, explained that the entry of patients’ escorts into Turkey was halted in March 2019 “due to several problems, most notably is when the patient returns to Syria, and the escort remains in Turkey to work or travel to European Union countries,” he said.

When the February 6 earthquake struck, Islam Suleiman, 46, was in the Turkish city of Antakya, where she had been receiving treatment for breast cancer for two years. Antakya was among the cities worst hit by the disaster, which claimed the lives of tens of thousands of people in Turkey and Syria. Traumatized by the experience, Suleiman returned to Idlib.

While in Turkey, Suleiman received 32 doses of radiation. “I am afraid to return to Turkey to complete my treatment for fear of the earthquake, and I am also afraid to leave my children alone in Syria, as I have been separated from my husband for nine years, and I cannot take them with me,” as no escorts are allowed to enter, she said.

Cancer patients and their families inside the Oncology Department at the Central Idlib Hospital, 26/07/2023 (Aladdin Ismail)

The Central Idlib Hospital, funded by the Syrian American Medical Society (SAMS), provides chemotherapy for six types of cancer, the head of the hospital’s oncology department explained. Treatment is available for “breast, ovarian and colon cancer, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma that affects the lymphatic system, and lymphocytic leukemia that is acute in children and testicular cancer,” he explained. “Free intravenous infusion of doses for other types of cancer” is also provided, he said, around “1,200 doses per month.”

The hospital provides “some of the medicine for free, while some types of medicine are purchased by patients,” he added. Radiotherapy and immunotherapy devices, however, “are not available, because they are very expensive, which forces us to refer patients to receive treatment in Turkey,” the doctor said.

Due to the closure of Bab al-Hawa border crossing to cancer patients following the February 6 earthquake, Syrian activists launched a campaign on social media, on February 27 named “Save the Cancer Patients,” urging Turkish authorities to allow about 3,300 cancer patients in northwestern Syria to enter its territory for treatment. The campaign met with widespread interaction locally and in the media.

A sit-in for cancer patients in Bab al-Hawa Square near the border crossing, 22/07/2023 (Mustafa Hallaq)

Six cancer patients, including children, lost their lives during the closure of Bab al-Hawa border crossing. Among the deaths were two patients who lost their lives after being interviewed for the purpose of this report. They are Muhammad Jalmoud and Mahmoud Muhammad from the city of Afrin.

Expired medication

The situation of cancer patients in the areas controlled by the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES) is not much different from the northwest. Syria’s northeast also lacks specialized care centers and hospitals for cancer patients, driving them to seek out treatment in other areas of control, namely Syrian government-controlled areas or the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI). Turkey is not an option, as border crossings with AANES areas are closed.

Consequently, patients, and particularly cancer patients, in AANES areas are paying the price for the significant decline in Syria’s health system, as well as local and regional political tensions. Some, like Abdul Rahman Ali Rasoul, 67, are forced to take expired medications.

Rasoul, who suffers from cancer, lives in the Hasakah countryside city of Amuda. His doctors have emphasized that he needs to take his medications regularly, and maintain the regimen to avoid any health repercussions. But after the Semalka border crossing with neighboring Iraq was closed on May 11, he was forced to “take expired medicine,” he said. Rather than the drugs helping him, he began to suffer from “a loss of balance,” so stopped taking the medication immediately.

Abdul Rahman Rasoul, a cancer patient, sits on a chair in the garden of his house in the Hasakah countryside city of Amuda, in northeastern Syria. An expired package of medicine sits before him, 6/6/2023 (Mustafa Mustafa)

Twelve years ago, Rasoul noticed black spots on his feet, and was ultimately diagnosed with leukemia. So began his cancer treatment journey, moving between Damascus, Turkey and Iraqi Kurdistan. “I now have three dose booklets, each in a different language and issued by a different entity,” he said.

After about two-and-a-half years of Rasoul receiving treatment in Turkey, the Darbasiyah border crossing, known as Martyr Gumkin crossing on the Syrian side and Shanyurt crossing on the Turkish side, was closed for “security” reasons. The crossing was designated for humanitarian cases. With it closed, Rasoul turned to the KRI , which is his only destination until now.

However, periodic closures of the Semalka border crossing, mostly due to political differences between the AANES and KRI authorities, impact the treatment of chronically ill patients, including those with cancer like Rasoul.

“The case of the Semalka crossing is no different from the case of the Darbasiyah crossing,” Rasoul said with disappointment. “When the latter was closed, I crossed the border illegally to get my doses in Turkey,” but the smuggling routes to the Kurdistan region are “very expensive, ranging between $3,000 and $4,000, in addition to the fact that my current health condition does not allow me to go through smuggling routes,” he added.

An archival photo of the Semalka border crossing between northeastern Syria and Iraqi Kurdistan (North Press)

After years of illness, Rasoul is unemployed, while he also supports his disabled daughter. Were it not for “charitable people,” as Rasoul described them, referring to community assistance, he would not have been able to pay for treatment.

On May 11, 2023, the AANES-affiliated Semalka border crossing administration published a statement announcing that the administration of the Fish Khabur crossing—that is, KRI authorities—had decided to close the crossing to both commercial and humanitarian traffic until further notice, for unknown reasons.

The Syrian side accused the KRI administration of linking the crossing to political matters, without providing additional details. However, the decision to close the border came after “the Autonomous AANES prevented a Kurdish National Council (KNC) delegation from crossing into Iraqi Kurdistan,” according to an official KNC statement. The crossing reopened nearly three weeks after it was closed.

Rasoul recalled the closure, saying: “It was difficult for me, and the delay in reopening it heightened my concerns.” During that period, he requested help from several parties to enter Iraqi Kurdistan, but was told approval had to come from the other side of the border.

The Health Committee at the Semalka crossing, which is affiliated with the AANES-affiliated Health Authority, confirmed that it approves the entry of 10-to-15 cancer patients a day into the KRI to receive treatment free of charge, except for tests. The committee said in a statement to the reporters that delays were due to authorities on the other side of the crossing.

“During the closure, we did not have any alternative measures to help those patients other than waiting for the crossing to resume its operations,” the health committee source said.

Cancer spreads in AANES areas

Rasoul is one of 7,000 cancer patients in northeastern Syria registered with the AANES Health Authority, according to the latest figures provided by Dr. Johan Mustafa, co-chair of the authority. Mustafa said these numbers are “approximate,” due to the lack of a comprehensive center specialized in cancer patients in the area.

While there are no accurate figures of cancer patients in northeastern Syria, Dr. Alan Khalaf, an oncology and chemotherapy specialist, pointed to an increase in the number and spread of tumor diseases, especially cancer. He linked a high rate of cancer to air pollution in the region.

Khalaf, who previously worked at al-Biruni University Hospital in Damascus, and currently lives in Qamishli, said, “breast tumors constitute the highest percentage among women in the region, and the death rate of this type [of cancer] is high, due to environmental and air pollution.”

“If we assume that women with breast cancer make up 30 percent of the tumors in the area, and we compare that with the percentage of another region, the death rate here will be higher,” Khalaf said. “Environmental pollution plays a major role in activating mutations that feed the tumor and increasing the oxidative stress within cancer cells, as several studies confirm.”

The World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer, in a press release published in October 2013, classified outdoor air pollutants as carcinogenic to humans and a major cause of cancer deaths.

The agency indicated that there is “a positive association” between outdoor air pollution and an increased risk of bladder cancer. “Particulate matter, a major component of outdoor air pollution, was evaluated separately and was also classified as carcinogenic to humans.”

In October 2022, a study entitled “The Economic Cost and Environmental and Health Risks of Car Exhausts in North and East Syria” was issued by the Qamishli-based al-Furat Center for Studies. It pointed out that 40,096 vehicles entered AANES areas through the Semalka and Manbij border crossings during the preceding five years. “The issue of air quality is absent from the planning mechanisms, or even consideration, of relevant AANES institutions,” the study read, leading in turn to “an increase in toxic emissions into the atmosphere, raising the level of air pollution” and consequently “an increase in the level of diseases resulting from it.”

The study indicated that “the issue of air quality in cities has not been included in the calculations and plans of the Autonomous Administration until now, which causes an increase in disease cases in the region, especially those serious and incurable diseases, such as cancers or strokes, which have been observed to increase in recent years.”

A journey to find treatment

“You are suffering from cancer, and you must have an operation as soon as possible, otherwise it will spread all over your body.” Hamida al-Hamoud, 43, from Raqqa city, recalled what her doctor told her a year ago. “It was a shock,” she said.

Al-Hamoud, a mother of four, suffers from financial difficulties, especially as her husband is partially paralyzed, she said. When she was diagnosed, she had no choice but to ask family members for help covering the costs of a trip to Damascus for treatment.

Due to the lack of cancer treatment facilities in AANES areas of northeastern Syria, patients like al-Hamoud are forced to travel long hours, for hundreds of kilometers, to seek treatment in major Syrian cities. A single trip can take as long as a full day.

“On my first visit to Damascus, I was crying all the way. I was not worried about myself but about my children,” al-Hamoud said. “I was deprived of seeing them.” She received one dose of treatment every three or four days, which forced her to stay in the capital because the road between Raqqa and Damascus is difficult.

Al-Hamoud feared “neglect in public [government] hospitals in Damascus,” which drove her to “undergo a mastectomy at Dar al-Shifa Hospital, which is private,” she said. She would not have been able to do so “without the help of some philanthropists, because the operation was very expensive,” she said.

One of the most difficult situations that al-Hamoud has faced during her treatment journey is paying for “chemotherapy pills,” which she uses even after her surgery, because they are not always available in the market. “I feel devastated when I cannot find the medicine, and I think—What if I do not take the medicine? Will the disease spread throughout my body? Will my life simply end? How will my children manage?”

The Syrian government’s Qamishli-based Syrian Society for Child Cancer Treatment and Care (CCS) provides some treatments, but they are not enough, a CCS source said. “Better services were supposed to be provided in the center, such as providing doses and medicine, administering doses and medical consultations for free, but due to the difficulties in finding and transporting medicine [in Syria overall], the services provided are not proportionate to the percentage of cases in the region,” he said. The medicine available in the center is “little,” the source added.

The entrance to the Oncology Department at the National Hospital in Raqqa, north-eastern Syria (Web)

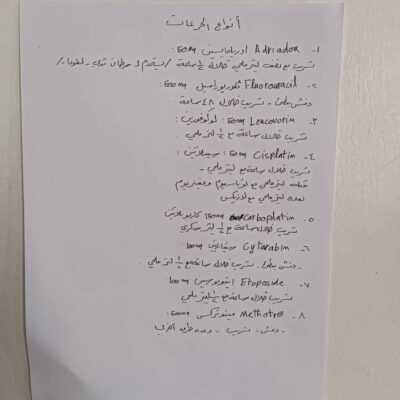

On July 12, 2023, the Oncology Department of the Syrian Cancer Society (SCS) was opened at the National Hospital in the city of Raqqa, in cooperation with the Health Committee of the AANES.

During the first days after it opened, the department received 125 cancer patients, according to Dr. Ahin Muhammad, director of the department, noting that emergency medications and eight types of chemotherapy doses are provided, in addition to other services.

The department still lacks special examinations for cancer patients, types of chemotherapy and specialized medical staff, which is the case in the region in general, Muhammad explained.

A list of the types of chemotherapy drugs available at the Oncology Department at the National Hospital in Raqqa, 22/07/2023, (Ahin Muhammad)

“The financial capabilities of the AANES are not sufficient to open a specialized, integrated center in the region, on top of the lack of specialists,” Mustafa, the co-chair of the AANES Health Authority, said. However, “there are attempts and promises to fill this gap.”

“The lack of recognition of the AANES is an obstacle to the process of importing medicine and [chemotherapy] doses for cancer patients into the region,” Mustafa added. Some medicine enters the area illegally, “and therefore are not subject to health control and supervision,” he added. Despite efforts to coordinate with the Syrian government, “the latter politicizes the issue and does not allow the opening of channels for humanitarian communication,” he said.

A ‘transit card’ to move within Syria

For two years, Nariman Murad, 35 years old, living in al-Shahbaa area of the Aleppo countryside after her displacement from Afrin, in 2018, suffered from menstrual disorders. Doctors told her it was due to “psychological reasons,” but a medical examination a few months ago found the true cause was “cancer in [my] right ovary,” she said.

“Due to doctors’ negligence and failure to perform the necessary operation in a timely manner, the cyst on my ovary exploded leading to the deterioration of my health condition,” Murad, a widow and mother of four, added.

Facing her diagnosis, Murad had to grapple with something else: the need for a “transit card” for the Syrian government to allow her to cross from AANES-controlled areas in al-Shahbaa to government-controlled areas in Aleppo for treatment. The card is akin to “a passport,” without which residents cannot move between two Syrian regions, she said, noting that the costs of issuing it may reach SYP 400,000 (about $30).

In this context, a source from al-Shahbaa, requesting anonymity for security reasons, said the area has been besieged by the Syrian army’s 4th Division since August 2022, which “pushes many people in al-Shahba to reach Aleppo through illegal routes, to avoid passing through the 4th Division checkpoint, which imposes fees to cross, not to mention the harassment people may be exposed to at the checkpoint.”

The Syrian government controls the access of basic supplies and humanitarian aid to AANES-territories in northwestern Syria, which include Sheikh Maqsoud and al-Ashrafieh, north of the city of Aleppo, and more than 50 villages in al-Shahbaa region.

The cost of delayed treatment

Syrian cancer patients often discover that they have this “malignant” disease, as it is called, by chance when they are being examined for other ailments. Therefore, it is discovered at a late stage, and requires rapid treatment to prevent it from spreading or worsening. But urgent treatment is not available to many patients, due to the division of the country into areas of influence, which limits the movement of Syrians on their land or outside of it.

An activity organized by the “Farah Center for Children with Cancer” in the town of al-Maabada (Girkê Legê) in northeastern Syria, 24/06/2023, (Mustafa Mustafa)

The cost Hammoudi (a pseudonym), 13, paid for the delay in treatment for his leukemia was losing his vision. “The cancer cells recurred and he suffered from brain infiltration, then optic nerve atrophy,” Maha al-Ahmad, his mother, said.

“Hammoudi lost his studies and his future because of his loss of vision,” al-Ahmad said, holding back tears. “He needs a stem cell transplant, and this treatment is only available in Germany.” It is an extremely difficult option because “our financial situation does not allow us to travel,” she said, in addition to restrictions imposed on Syrians.

Today, Hammoudi’s only respite is the Farah Centre for Children with Cancer in the Hasakah province town of Maabada (Girkê Legê). There, he distracts himself from the disease eating at his body, returning home carrying the hope that one day he will find a spark to restore light to his eyes.

**

This is one of six reports produced as part of an investigative journalism training program across various spheres of influence within Syria. Syria Direct is publishing the final reports in cooperation with the Syrian organization that conducted the training.

This report was produced in Arabic and translated into English.