Syria’s nature lovers lament ecological losses after a decade of war

Nature is another victim of the conflict in Syria, once referred to by some as the environmental “crown jewel” of the Middle East. Inside the country and abroad, nature lovers still strive to monitor and preserve this natural heritage.

20 April 2021

AMMAN — “I used to go swimming on the banks of the Euphrates river in my childhood with my father. At the age of seven, I would watch the fishermen and ask them about the type of fish they caught and their local names; I would memorize them. My love for wild species increased, and I became acquainted with them,” Nader al-Salem (a pseudonym) recalled nostalgically in an interview with Syria Direct.

Al-Salem’s passion for the Euphrates river only grew stronger over time. He became an expert in local biodiversity, amassing pictures, observations and data about the ecosystems of the Euphrates basin and the Syrian Badia, an arid steppe stretching out across the east of Syria.

In 2015, al-Salem fled to Damascus following the destruction of his home in Deir e-Zor and the loss of his most prized possessions: his binoculars, a telescope, his camera and hundreds of scientific documents and notes collected over the course of twenty years.

“Wildlife is my life, and I cannot imagine life without it,” al-Salem said, now living far away from the Euphrates he loves but still working towards the preservation of nature in his country.

The toll on biodiversity

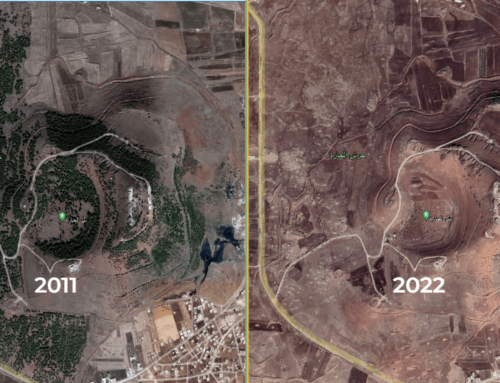

Over the past ten years, in addition to widespread destruction and the catastrophic human toll of the conflict, Syria has witnessed the insidious impact of war on its natural environment, a toxic legacy that will affect the coming generations.

Across much of the country, the local administrations previously responsible for managing wildlife or forests are in shambles. Poaching is on the rise in certain areas, catalyzed by rampant food insecurity, the lack of enforcement agencies and the increased availability of weapons.

War has accelerated the destruction of habitats. In coastal regions, forests are ravaged in the summer by large fires. Northern Syria is plagued by increasing soil and water pollution resulting from makeshift oil refineries. Economic hardship has increased illegal logging due to the shortages in heating fuel and its high cost.

“I have worked in most, if not in all countries of the region, but for me Syria was the gem of the crown.”

Syria’s nature is being pillaged, with wildlife trafficking on the rise. In 2019, Turkish police seized 2,000 goldfinches smuggled from Syria, and Lebanon has become a market for smuggled birds from Syria. Several wild and protected species fall prey to trafficking, including chameleons. Jordan is also considered a transit route for rare species smuggled from Syria to markets in the Gulf.

While it is difficult to obtain data on how Syria’s biodiversity has fared since 2011, it is likely that some endangered species are increasingly threatened. One emblematic case is the northern bald ibis, feared extinct from the Syrian Badia. The three known representatives of Syria’s bald ibis population have not been spotted at their usual breeding site in Palmyra since 2014.

Their probable extinction cannot be blamed on the conflict alone but also the culmination of years of decline linked to the environmental degradation of the Badia. Yet their extinction brought an end to the hopes of conservationists who dedicated years trying to restore the birds’ population in its natural rangeland. Many worry that decades of conservation efforts will be similarly lost to the war.

“Syria is so valuable in terms of biodiversity,” Tomas Axén Haraldsson, a freelance conservationist with experience in Syria and affiliated with the Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME), told Syria Direct. “The country has a huge diversity in terms of rainfall, varied ecosystems like desert and wetlands and the Euphrates river.”

In addition, it is located on the path of many Eurasian birds migrating south in winter, which makes its wetlands an important spot for birdlife beyond Syria.

“I have worked in most, if not in all countries of the region, but for me Syria was the gem of the crown,” Laith al-Moghrabi, Lead Ecologist for the private consultancy Fieldfare Ecology, told Syria Direct. He worked on two conservation projects in Syria, including in Jabboul, a wetland of international importance located near the northern city of Aleppo.

“Working in Jabboul was very, very special – there is no other place that is as important as it is in our region,” al-Moghrabi said. The site was identified as the only known breeding site for flamingos in West Asia.

The conservation landscape before 2011

Powerful dynamics of environmental degradation were already underway in Syria decades before the war. These played a major role in destabilizing livelihoods in rural areas and fueling the social tensions that erupted into protests in 2011.

The Syrian Badia, covering 55% of the country’s territory, was damaged by overgrazing. Aggressive intensive agricultural policies and the expansion of farmland contributed to the depletion of Syria’s limited water reserves. The number of wells increased from 135,000 in 1999 to 225,000 in 2010, and Syria’s water table plunged by up to 40 meters. From 2006 to 2011, Syrian farmers suffered from impoverishing droughts, which led to the displacement of an estimated one million people. It seemed that little was being done to deal with the impending environmental crisis.

Still, “before the conflict, there was some kind of positive feeling in the air in Syria for conservation,” Haraldsson noted. “Syria had a lot of talented young academic people.”

Several international conservation projects were taking place, some with the support of Syria’s First Lady Asma al-Assad, who was involved in the conservation of the northern bald ibis. Protected areas were established, and management plans were drafted.

Haraldsson, involved in Syria with OSME, says the organization managed to get books on wildlife published in Arabic and implemented some ecotourism projects in collaboration with other stakeholders, including INGO Birdlife International.

“When the conflict broke, it became a nightmare. Anyone who could leave left, including many conservationists who had contacts abroad. Some are now living in Europe or camps in Jordan and Turkey.”

While the working environment for NGOs in Syria was always restricted, several sources interviewed by Syria Direct described a somewhat more permissive context for environmental projects, perceived as relatively harmless politically. The leading environmental organization was the Syrian Society for Conservation and Wildlife (SSCW), which carried out projects in cooperation with international partners.

However, “when the conflict broke,” Haraldsson added, “it became a nightmare. Anyone who could leave left, including many conservationists who had contacts abroad. Some are now living in Europe or camps in Jordan and Turkey.”

What future for conservation in Syria?

Today, the situation in Syria does not lend itself to carry out badly-needed conservation projects. Insecurity and the presence of unexploded ordinance limit the possibility to conduct any fieldwork.

“The Syrian Badia was planted with mines; therefore, a lot of hunting and grazing stopped,” al-Salem explained. As such, “wildlife certainly recovered greatly due to the absence of activities there.”

“Some regions might have actually seen less poaching and hunting because it was too dangerous to go around with a rifle, or because people could not go fish, harvest and tend to their fields,” Haraldsson noted. “Some areas may actually have witnessed less poaching and illegal bird hunting.”

Overall, “it is hard to assess and verify the extent of environmental damage linked to the conflict,” Haraldsson added. But one thing is certain: “Any good efforts to conserve wildlife are thrown aside when people need to feed themselves.”

Despite this challenging situation, some conservation projects are still ongoing, mostly in regime-controlled areas, including a small UNDP-funded project to support the local communities around the Jabboul site, according to a blog post written by researcher Nabegh Ghazal on behalf of the SSCW.

On social media, nature lovers still exchange knowledge and observations. One Facebook profile belonging to a Syrian environmentalist based in Latakia province manages no less than 42 different pages dedicated to the flowers, animals, mushrooms and landscapes of Syria, with a following of a few thousand Facebook users. A handful of Syrian naturalists are also active on an online collaborative platform where they regularly upload photos and data about the species they sight. These activities seem mostly concentrated in the coastal areas, away from the conflict lines.

“It was a country that I worked in and that I developed a strong connection with, and it’s very sad to see that very little was done before 2011. A lot had already been lost, and now we are just collecting the pieces”

However, opportunities for new generations to connect with nature are dwindling. “Making a living has become a priority, and it takes all the time one has,” a follower of a Facebook page dedicated to Syrian wildlife told Syria Direct on condition of anonymity.

“Frankly, ecotourism activities like hiking and camping almost stopped. Participants are normally young people and university students, people used to come to the countryside from Damascus, but since a year all groups stopped. Even the cost of transportation, they are not able to cover it,” the man regretted.

With shrinking opportunities to carry out fieldwork, growing pressures on habitats, and a dismal humanitarian context, there is little hope that Syria’s environmental situation will improve in the foreseeable future.

“It was a country that I worked in and that I developed a strong connection with, and it’s very sad to see that very little was done before 2011. A lot had already been lost, and now we are just collecting the pieces,” al-Moghrabi regretted.

But inside the country and abroad, communities of nature lovers persist, united by common goals. This pool of experts and amateurs constitutes Syria’s best hope to restore, one day, damaged ecosystems for the benefit of all. “Whenever it is safe for me to do so, I will definitely go back and do some research there,” al-Moghrabi added.