Buildings in Damascus’ al-Hajar al-Aswad demolished, rubble sold

In al-Hajar al-Aswad, south of Damascus, buildings are steadily being demolished—regardless of whether they are structurally sound—with the rubble sold for profit under the eyes of regime forces. Some fear demolitions could be a precursor to expropriations under redevelopment plans.

19 October 2023

DAMASCUS — In al-Hajar al-Aswad, a city seven kilometers south of the Syrian capital Damascus, building after building has been demolished over the past two months. Under the guise of “rubble removal,” contracting companies tear apart buildings—not only those deemed safety hazards by local authorities, but also those that are undamaged and structurally sound.

“Homes are demolished and stripped of iron,” Abbas al-Shami (a pseudonym), a 45-year-old who is from al-Hajar al-Aswad, told Syria Direct. “Intact houses are destroyed in broad daylight.”

Al-Shami lives in a rented house in the al-Tadamon neighborhood of south Damascus, less than three kilometers away from his home in al-Hajar al-Aswad. His family is one of 37,000 displaced families that hoped to return to the city after regime forces regained control in 2018, the head of the al-Hajar al-Aswad city council, Khaled Khamis, told al-Watan newspaper. But he was not allowed to return, until earlier this year.

In March 2023, Reef Dimashq provincial authorities began to allow residents to return. Out of 3,100 applications, 2,700 were approved, city council head Khamis said. However, only around 1,000 individuals—roughly 200 families—have actually gone back, according to The Syria Report.

Damascus retook control of al-Hajar al-Aswad and the neighboring Yarmouk camp in May 2018, following an agreement to relocate members of the Islamic State (IS)—which previously held the area—to the eastern Syrian desert.

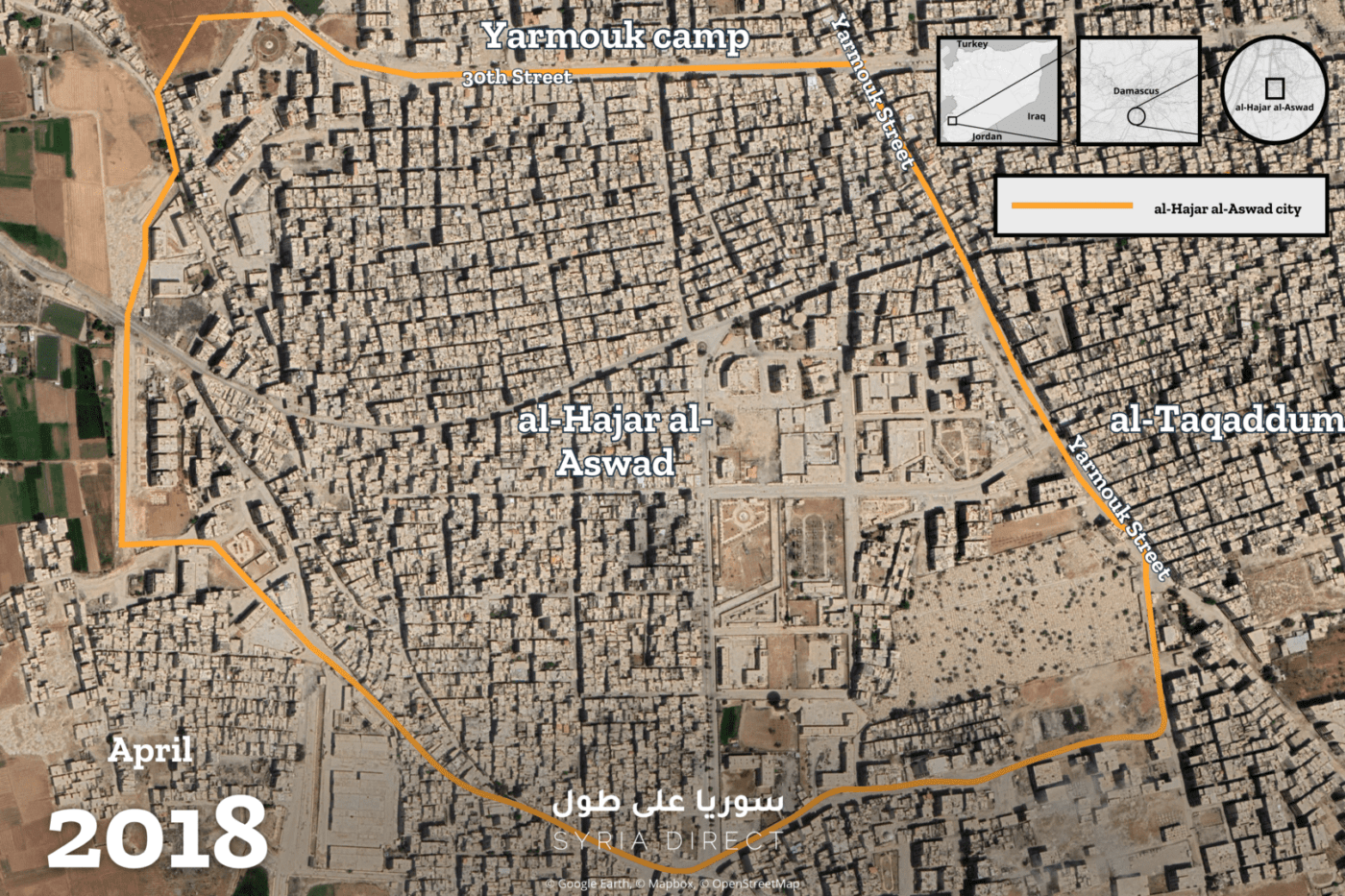

Al-Hajar al-Aswad was home to about 400,000 people before the 2011 uprising. It consists of several neighborhoods, including al-Thawra, Tishreen, al-Jazira, al-Wihda and al-Istiqlal, as well as a section of 30th Street that it shares with the Yarmouk camp.

As in neighboring Yarmouk, buildings in al-Hajar al-Aswad have been looted and destroyed in the years since the city was retaken, the rubble stolen. “Demolition and theft has not stopped since 2019,” al-Shami said. The Action Group for the Palestinians of Syria (AGPS) has reported multiple times that al-Hajar al-Aswad, where “thousands of Palestinians” lived, “household furniture, marble, tiles and iron bars from destroyed buildings have been looted and stolen.”

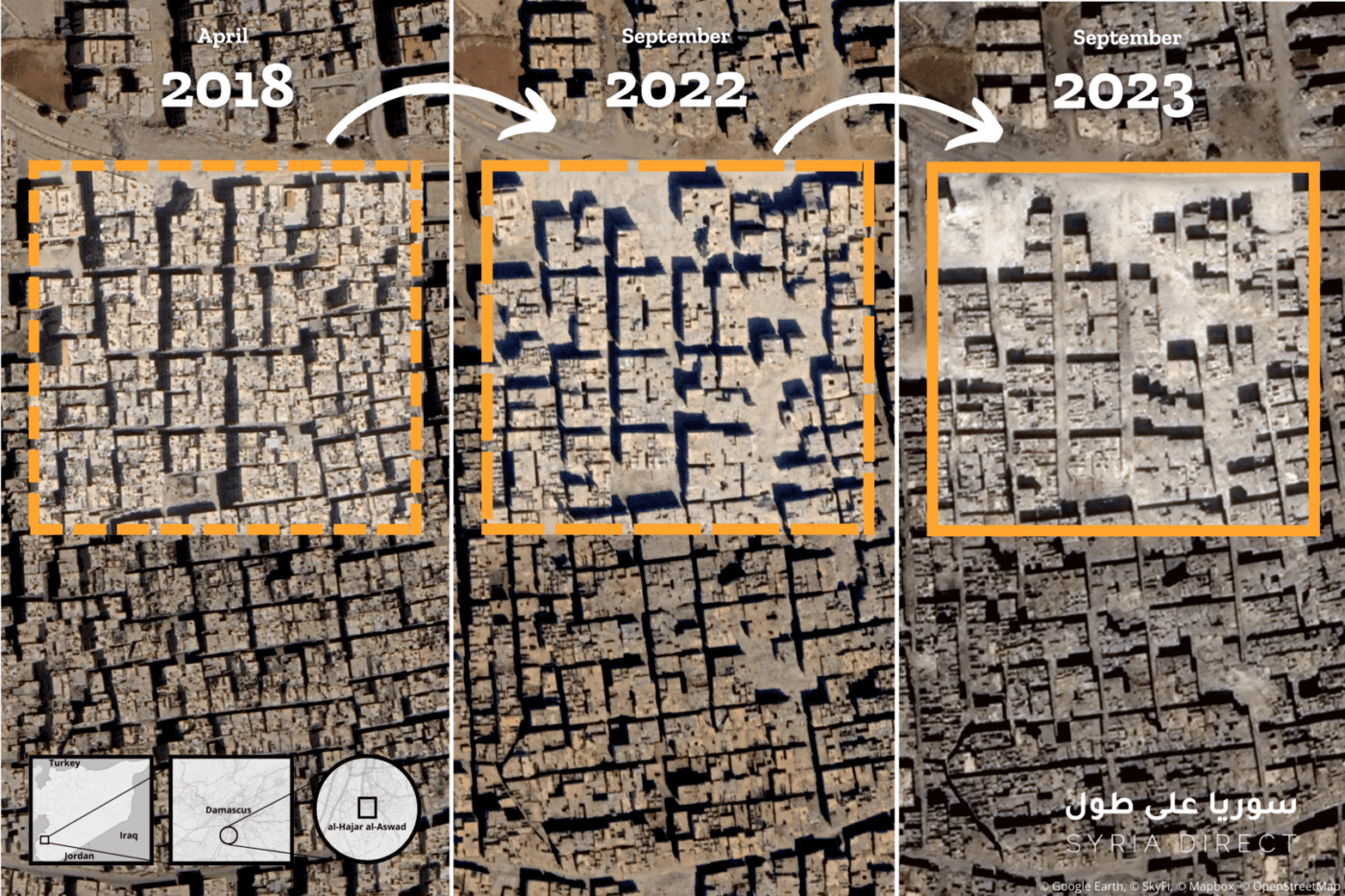

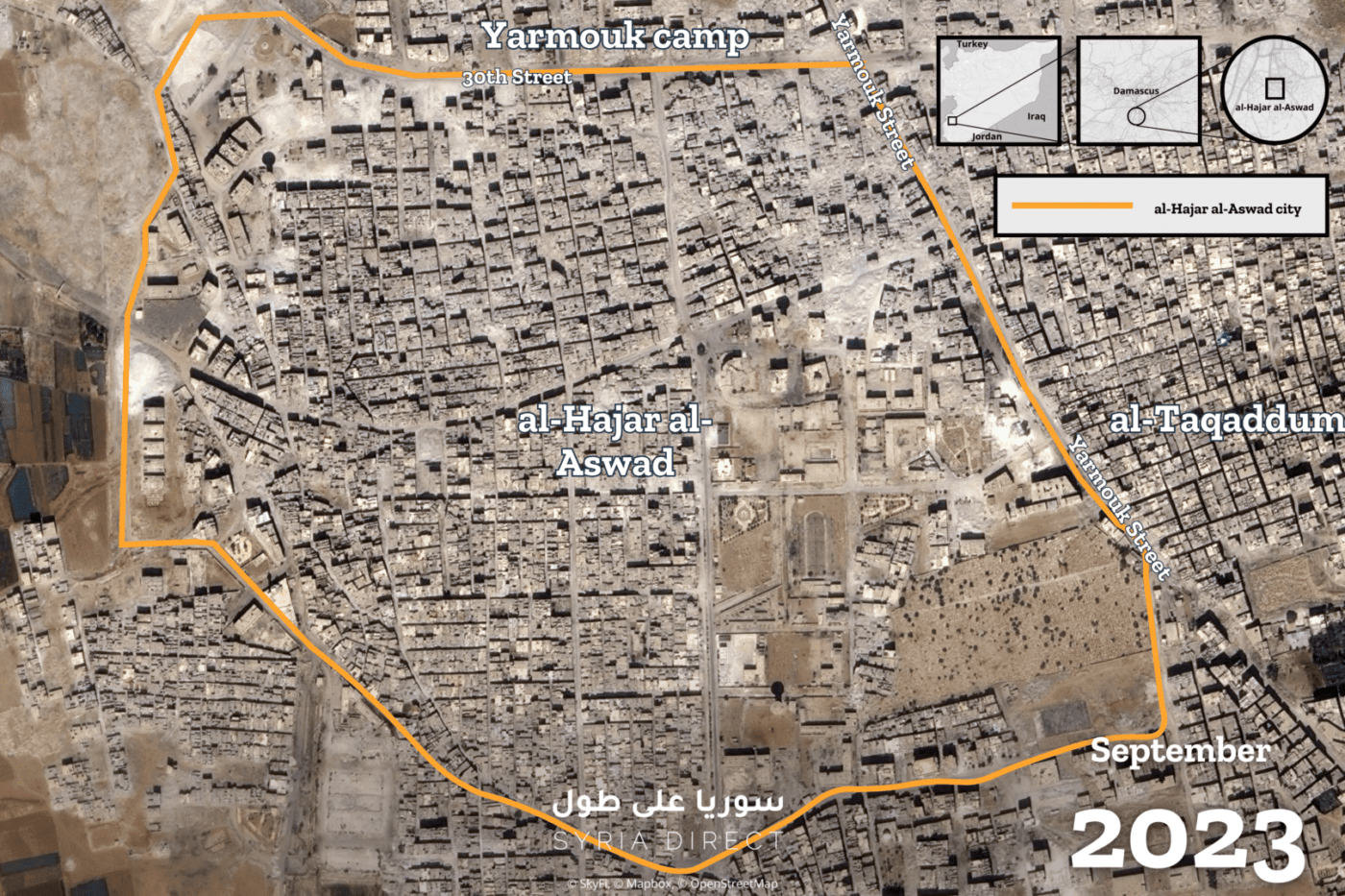

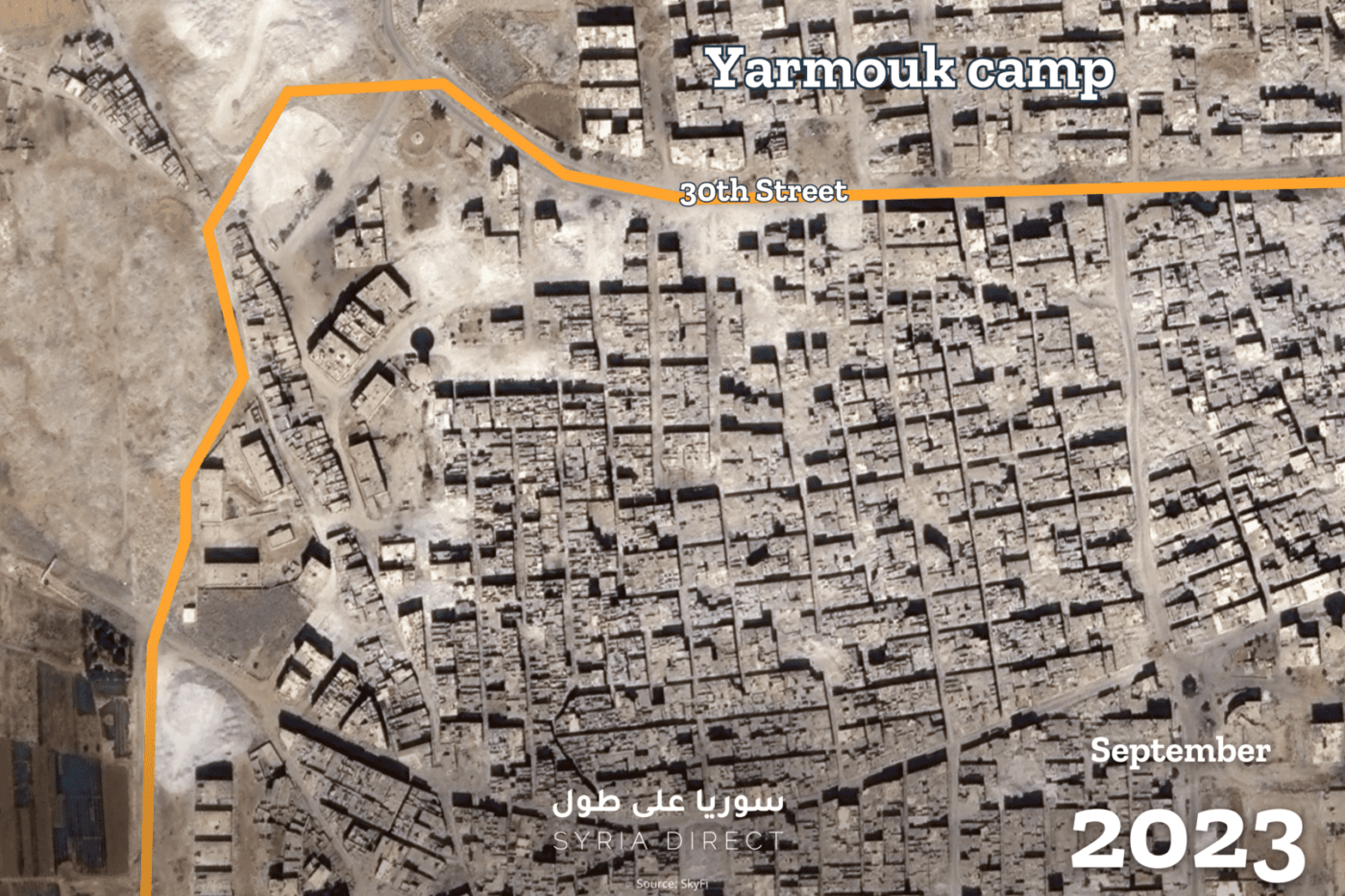

Satellite images of al-Hajar al-Aswad show a greater number of demolished buildings in 2023 compared to 2018, when Damascus retook control of the city from IS (Google Earth/SkyFi/OpenStreetMap/ Mapbox/Syria Direct)

‘They rob our homes’

In early 2023, Reef Dimashq provincial authorities allowed residents of al-Hajar al-Aswad’s al-Wihda and al-Istiqlal neighborhoods to return. But residents from the al-Jazira neighborhood and part of the 30th Street neighborhood were barred from doing the same, ostensibly because most residences there were destroyed.

In reality, buildings in the two neighborhoods are actively being destroyed through arbitrary demolitions, multiple residents of al-Hajar al-Aswad told Syria Direct. Some buildings in neighborhoods whose residents did return are also being demolished, they added.

A year and a half ago, al-Shami obtained approval to “clean and repair” his home in the al-Thawra neighborhood from the al-Hajar al-Aswad municipality after paying SYP 50,000 for a “house inspection fee” (approximately $12.30 according to the exchange rate at the time). Al-Shami fixed up his home and decided to move in, but when he brought his furniture he found the newly repaired structure’s “doors and windows had been removed—even its roof was demolished,” he said.

“They rob our homes right before our eyes, as though there is no state,” he added, emphasizing that those involved in the theft “are protected, and the iron-laden trucks leaving town are not stopped by anyone, though Syrian army checkpoints are spread throughout the area.”

Ghalib Anez, a legal consultant and member of the Damascus Provincial Council, said “there are hidden hands at play,” without accusing any specific party. Speaking to Syria Direct, he called for all people from al-Hajar al-Aswad to be allowed to “return and restore their homes following a technical inspection, as happened in the city of Darayya.”

Trading in rubble

Al-Shami once dreamed that the war would end so he could return home. Now, he finds himself wishing “it hadn’t ended.” His home withstood the fighting in al-Hajar al-Aswad. It was only after that “demolition operations targeting undamaged homes began, without any accountability.”

Al-Jazira neighborhood is where the most extensive demolition operations are currently taking place, al-Shami said. “If demolition continues at this pace for another month, the entire neighborhood will be reduced to rubble,” he added. Al-Shami estimated that “10 cars loaded with iron and recyclable materials leave the neighborhood every day, heading to the Hamsho iron factory in the industrial city of Adra.”

Muhammad Saber Hamsho, the plant’s owner, is accused of being “the top scrap dealer” working with the Syrian army’s 4th Division which is involved in looting rubble from destroyed buildings.

Two additional sources from al-Hajar al-Aswad—who requested anonymity for security reasons—also told Syria Direct that rubble removal contractors work with the 4th Division to strip iron from buildings to sell to Hamsho for recycling.

In a July report, the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights (SOHR) also accused members of the pro-Damascus National Defense Forces (NDF) militia of “demolishing damaged buildings and houses, including some intact buildings” in al-Hajar al-Aswad.

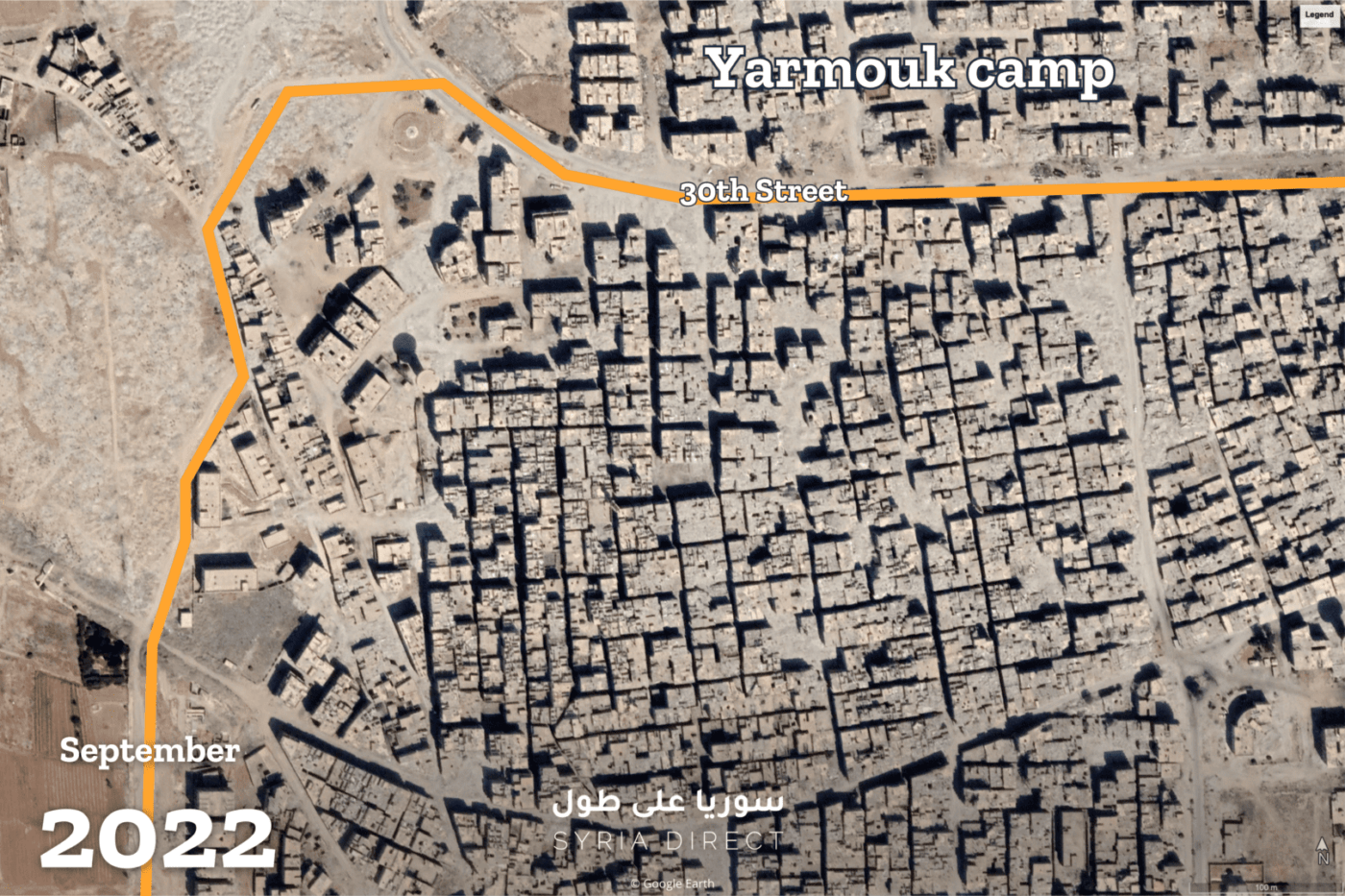

Satellite images show ongoing demolitions in the north of al-Hajar al-Aswad. A picture taken on 29/9/2023 image shows an increase in the number of demolished buildings compared to 7/9/2022 (Google Earth/SkyFi/Syria Direct)

The demolition and looting of homes in areas retaken by Damascus has become a systematic practice. Regime security and military services in several parts of the country—such as the southern and eastern Idlib countryside—advertise “affiliation contracts” with extra pay for work in demolition operations.

Redevelopment

Said Muhammad (a pseudonym), 55, believes “the government does not want residents to return to their homes. By giving rubble removal contractors free rein, and not restoring services in al-Hajar al-Aswad, it achieves its objective.”

In 2021, Muhammad’s request to restore his apartment in al-Hajar al-Aswad’s Tishreen neighborhood was approved, but “a month later, I found the building’s staircase leading to my third-floor apartment demolished,” he told Syria Direct. “It felt like they were telling me I couldn’t return.”

In response to complaints from al-Hajar al-Aswad residents regarding arbitrary home demolitions, including those of buildings with no demolition orders, city council head Khamis told Athr Press last month that “house inspections are carried out by specialized engineers from the structural safety committee of Reef Dimashq Province’s Technical Services Directorate. The committee then decides whether to demolish or restore the building based on specific data.”

While confirming that demolition vehicles are affiliated with the public safety committee and tasked with demolishing buildings deemed at risk of collapse, Khamis denied any municipal involvement in thefts. Such matters should be looked into “by the security forces, not the municipality,” he said.

Amid property rights violations in various areas reclaimed by Damascus, particularly those that include informal housing, displaced residents fear that violations against their property will be legalized under certain laws, such as Law No. 10 of 2018.

Law 10 allows Damascus to create urban redevelopment areas across Syria, and has sparked controversy in recent years surrounding the possibility of the law expropriating millions of people.

The law allows al-Hajar al-Aswad to be declared a redevelopment zone, ostensibly to address the issue of informal settlements, and “convert individual ownership into shares, without compensating those who have lost their ownership documents,” Manhal al-Khaled, a lawyer specialized in real estate ownership, told Syria Direct.

These concerns are amplified by the fact that “the regime has allowed executive authorities the freedom to choose which laws to use, given the overlapping and unclear real estate laws,” al-Khaled noted. “It is impossible to tell which law will be enforced when a redevelopment zone is established, and which authority will govern it.”

In 2021, Damascus, in coordination with the Syrian Housing Ministry’s General Company for Engineering Studies, began preparing new detailed redevelopment plans for areas surrounded by “structurally unsound informal housing,” including al-Hajar al-Aswad, according to the state-controlled Syrian Arab News Agency (SANA).

In February 2022, Abdul Razzaq Dhamiriya, Reef Dimashq province’s Director of Decision Support and Regional Planning, stated that “the study for al-Hajar al-Aswad has commenced, and the first phase has been delivered. The full city redevelopment plan is expected to be completed by the end of June, with infrastructure preparations set to be finished by next July.” He added that the rubble clearance operations were 75 percent complete.

In November 2022, the Facebook page “Gathering of Displaced al-Hajar al-Aswad Residents” posted an update about the city in which it noted that buildings in “half, or most of the al-Jazira area” slated for redevelopment had been “removed.” However, neither the Damascus government nor the city council has announced that a redevelopment plan for al-Hajar al-Aswad has been issued. Nor have they confirmed any demolition operations based on redevelopment plans.

Commenting on that, a source from the Reef Dimashq provincial council told Syria Direct, requesting anonymity, that “no redevelopment plan for al-Hajar al-Aswad has been issued to date.” The source added that “the governing law for the city’s redevelopment is Decree No. 5 of 1982,” known as the Urban Planning Law, amended by Law No. 41 of 2002.

Law 41 allows the province to use authority granted to it under Decree 5 to identify areas for reconstruction or expansion. It also allows the province to draw up redevelopment plans for these areas, “granting it extensive authority to determine when and where redevelopment takes place without necessarily considering property owners’ interests or other factors such as conflict, displacement or asylum,” according to a 2022 report by Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ).

Weighing in on that, al-Khaled noted that “relying on Law No. 5 of 1982 may lead to some property seizures, as it empowers the executive authority to create and expand roads, build schools, parks and more.” He added that “the law prevents affected individuals from seeking legal recourse as it transfers this decision-making authority from the judiciary to a technical committee chaired by the governor and composed of several of his subordinates.”

According to al-Khaled, Damascus province instead “should have implemented Law No. 3 of 2018, despite its drawbacks, as it deals with the removal of rubble from buildings damaged by natural or unnatural causes.” This law also “solves the problem of not all property owners being present,” he added. Under Law 5, by contrast, requires property owners to be notified “either personally or through the media, which becomes challenging given that most residents of al-Hajar al-Aswad are displaced and hard to reach.”

Aniz highlighted that “al-Hajar al-Aswad has expanded well beyond the size defined in the 1987 redevelopment plan, stressing that allowing irregular [settlements] to grow exacerbated the problem, and that the first step towards a solution should begin with organizing the city and compensating impacted residents with alternative housing.”

Al-Shami, still living a few kilometers from his looted home in al-Hajar al-Aswad, said if Damascus is not serious about allowing residents to return, it should at least “preserve what remains of our properties and put an end to demolition and theft.”

**

This report was originally published in Arabic and translated into English by Nouhaila Aguergour.